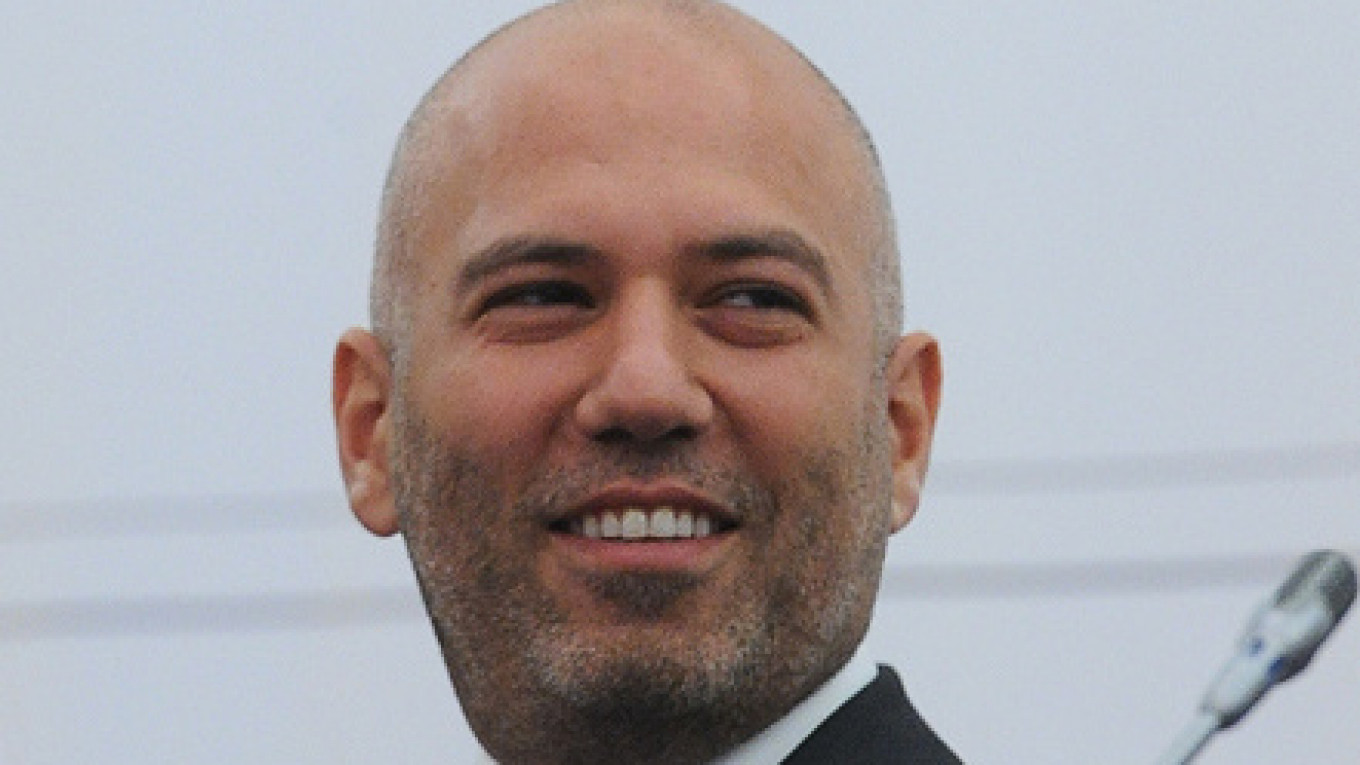

Denis Sverdlov emerged as the latest Russian tech billionaire last month, following the stock market launch of his hotly-tipped startup Arrival — an electric vehicle maker hoping to revolutionize the industry.

Sverdlov has more than two decades of startup experience both in Russia and internationally, and was a one-time deputy government minister, drafted in to help boost the country’s online development.

Born in 1979 in the Soviet republic of Georgia, he founded his first company — a corporate software tool named IT Vision — in 2000, immediately after graduating from university in St. Petersburg. He sold it three years later, before in 2007 becoming one of the co-founders of Scartel, the parent company of Yota — one of Russia’s most remarkable tech successes of the late 2000s and early 2010s.

With support from Sergey Chemezov, CEO of Rostec and one of Putin’s oldest friends, Yota pioneered the Russian Wi-Max and LTE markets, deploying the world’s first LTE Advanced network in Moscow.

The company also launched a — not very successful — innovative dual-screen smartphone, the patent for which Sverdlov co-authored.

Scartel’s telecom business was eventually acquired by Russian telecom major Megafon, while the smartphone manufacturing branch was sold to Rostec and a Hong Kong-based investment firm.

Into government

After his business success, and with Dmitry Medvedev returning to the prime ministership following his spell as President in 2012, Sverdlov became a government official — Deputy Minister of Communications and Mass Communications with responsibility for the internet and e-government projects.

Upon entering government Sverdlov hoped to realize “a unique chance to create an efficient regulatory system for the development of the industry,” he told the Kommersant newspaper.

However, he left this position just a year later, following new legislation which banned government officials from holding assets abroad.

He briefly headed a Rostec subsidiary before packing his bags, heading west and jumping back into tech entrepreneurship.

Back to business

In 2015, the serial entrepreneur moved to London and launched a $500 million startup fund called Kinetik.

The fund’s first investment was in Charge and Arrival — partner companies founded and headed by Sverdlov himself “with the idea to reinvent the way automobiles are made.”

Arrival first established itself in Enstone, near Oxford, at the site of the Lotus Formula One racing team. Sverdlov said this location made it easier to hire local top automotive engineers.

The company initially aimed to develop electric powertrains for trucks and buses — combining an electric battery and a one-liter fuel generator, resulting in a total range of about 700 kilometers for commercial vehicles.

Six years later, Arrival claims to have designed the “best-in-class electric vehicles with an exceptional user experience that are priced competitively against fossil-fuel vehicles and have a substantially lower total cost of ownership than both fossil fuel and electric variants.”

The firm hopes to be at the vanguard of a global boom in electric vehicles and lead the way in mass adoption — a journey it hopes will take it to $14 billion in revenue by 2024, Forbes magazine reported.

Arrival now positions itself as a full-fledged electric vehicle manufacturer, specializing in vans and buses. Aside from competing with the traditional vehicle makers in terms of product, Arrival also says it is “challenging the 100-year old automotive production process,” using its “microfactories” assembly method.

The idea behind the microfactories is that each can produce any vehicle from Arrival’s portfolio and be deployed “anywhere in the world within six months, using existing warehouses close to areas of demand,” and based on low capital expenditure.

Arrival has already inked contracts with some of the biggest logistics firms, themselves facing intense regulatory and consumer pressure to go green. UPS has ordered 10,000 battery-powered commercial vans for around $1 billion, with an option for another 10,000, Forbes reported. The vehicles are expected to be on the road by the end of the year.

The company claims its vans are lighter, more spacious, more energy efficient and roughly twice as cheap as its rivals, which include the Ford Transit and the Mercedes Sprinter.

The firm will also produce buses for mass transit, promising to lower carbon emissions. Launching at the height of the coronavirus pandemic last June, the company also said its buses come with reconfigurable layouts to support social distancing.

The McDonald’s of electric vehicles

Despite not having produced a single vehicle yet, the company has orders worth more than $1.2 billion and was valued at more than $13 billion when it launched on the Nasdaq exchange in March.

The first vans and buses are slated to start production towards the end of the year. And Sverdlov — and the investors who piled into its IPO, enabled by a special-purpose acquisition company — are bullish on the firm’s prospects.

“There are more than 560 cities in the world with a population of over 1 million people. Each of these cities could have a microfactory producing 10,000 vehicles specifically tailored for the needs of that market,” Sverdlov said.

“This model can be as scalable as McDonald’s or Starbucks.”

Sverdlov’s own fund was Arrival’s sole shareholder until new investors jumped in last year, including big names from the finance and automobile industries, such as Black Rock, Hyundai, Kia and UPS. Sverdlov also secured backing from Winter Capital, a Moscow-based international fund backed by Russia’s richest man, Vladimir Potanin.

Arrival went public in March via a merger with a special purpose acquisition company (SPAC) called CIIC Merger Corp — following the example of several other electric vehicle startups, which rode the SPAC wave in 2020.

The SPAC transaction between Arrival and CIIC was agreed in November last year. The combined company went public at the end of March, raking in $660 million in funding and giving the company a $13.6 billion valuation.

Sverdlov’s stake in the firm, along with his other investments, took his net worth to $10.6 billion when the deal closed, according to Forbes.

A Message from The Moscow Times:

Dear readers,

We are facing unprecedented challenges. Russia's Prosecutor General's Office has designated The Moscow Times as an "undesirable" organization, criminalizing our work and putting our staff at risk of prosecution. This follows our earlier unjust labeling as a "foreign agent."

These actions are direct attempts to silence independent journalism in Russia. The authorities claim our work "discredits the decisions of the Russian leadership." We see things differently: we strive to provide accurate, unbiased reporting on Russia.

We, the journalists of The Moscow Times, refuse to be silenced. But to continue our work, we need your help.

Your support, no matter how small, makes a world of difference. If you can, please support us monthly starting from just $2. It's quick to set up, and every contribution makes a significant impact.

By supporting The Moscow Times, you're defending open, independent journalism in the face of repression. Thank you for standing with us.

Remind me later.