Russia had to tread a fine foreign policy line in 2020. The country’s near abroad was rocked by unprecedented unrest as uprisings in Kremlin-friendly Kyrgyzstan and Belarus and war in the Caucasus challenged its influence in the region.

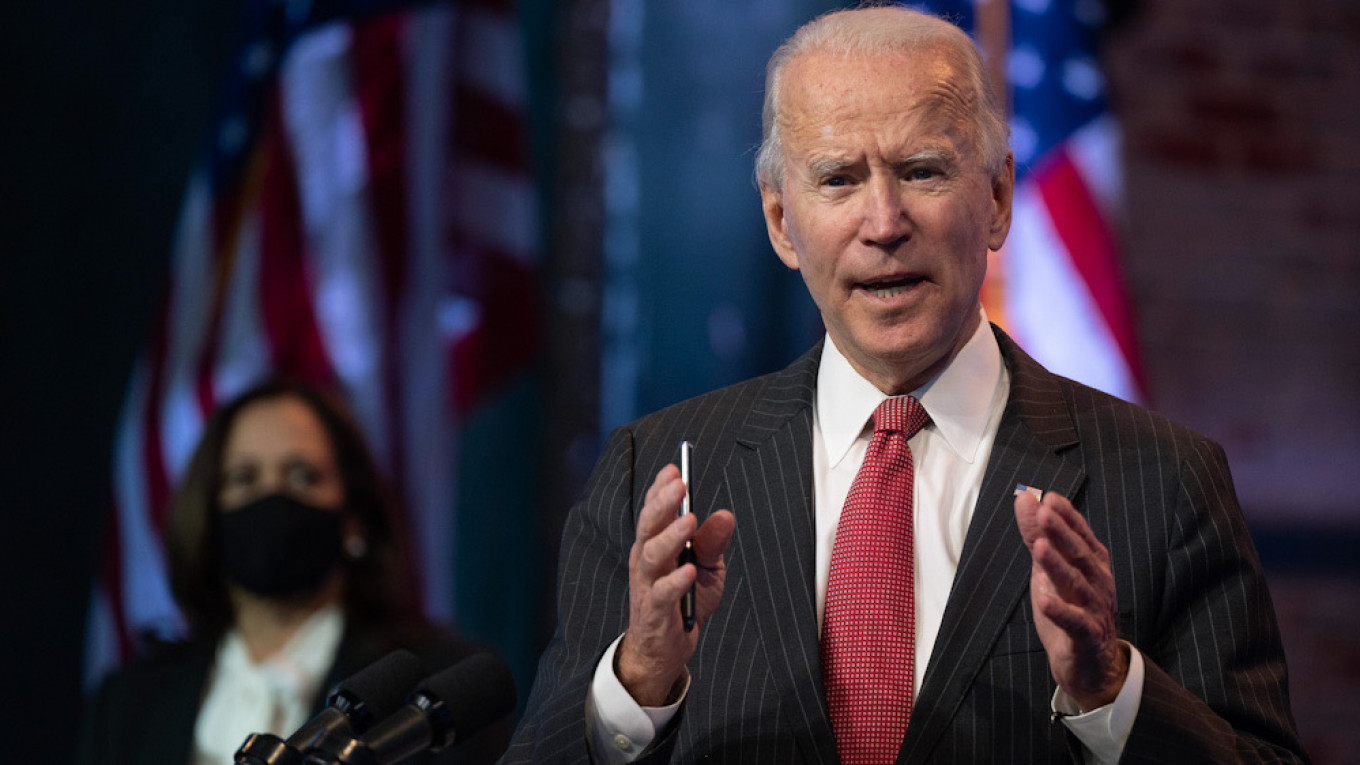

In the U.S., the election of Joe Biden is set to fundamentally change the course of American foreign policy toward Russia, while the poisoning of Kremlin-critic Alexei Navalny strained relations with Europe.

Russia also extended its global footprint by approving a naval facility in Sudan clearing the way for Moscow’s first military foothold in Africa since the fall of the Soviet Union.

But ultimately, 2020 will be remembered as the year of the coronavirus pandemic, and Russia is hoping its “vaccine diplomacy” will boost its image abroad as over 50 countries have shown interest in buying or producing Russia’s Sputnik V vaccine.

What does Russia hope to achieve in 2021? The Moscow Times asked 10 leading experts in Russian foreign policy to give their predictions for the coming year.

The South Caucasus is getting crowded

Thomas De Waal, Senior fellow with Carnegie Europe, specializing in Eastern Europe and the Caucasus region.

The Russian military is back in the South Caucasus for the first time since the mid-1990s. That is the main message about Russia’s plans for the Caucasus in 2021.

The ceasefire agreement which Russia brokered in November to end the six-week Armenian-Azerbaijani conflict over Nagorno-Karabakh brought in a Russian peacekeeping force of 1,960 men on a five-year mission.

This puts Moscow in the driving seat for further negotiations on normalization between Armenia and Azerbaijan. The deal also potentially re-opens road and rail connections for Russia to Turkey through

Azerbaijan which bypass Georgia. Russia’s political relationship with Georgia is still difficult, even if trade relations have normalized. It is consolidating its presence in Abkhazia, with an agreement that harmonizes legislation and, for the first time, allows Russians to acquire Abkhaz real estate. Moscow’s influence looks to be stronger in 2021 thanks to these interventions.

But it is no longer the hegemon it once was in the region. It is dealing with three sovereign states, and two often difficult clients in Abkhazia and South Ossetia. The South Caucasus is a crowded region which is also the neighborhood of the EU, Turkey, Iran and China. Russia’s tactical achievements there have as much to do with the disengagement of the other actors as its own success.

Ukraine loses its priority

Andrey Kortunov, Director General of the Russian International Affairs Council.

It seems very unlikely that 2021 will see a breakthrough in Russian-Ukrainian relations. First, both countries will inevitably have to focus on internal problems — overcoming their economic crises and the consequences of the Covid-19 pandemic.

As a result, both Moscow and Kiev will probably push foreign policy considerations to the back burner.

Second, a shift in the political balance of power within the country has weakened Ukrainian President Volodymyr Zelensky’s position, making it less likely that Kiev will implement the provisions of the Minsk Agreement fully. In all likelihood, demands will grow louder to review the agreement and exclude those provisions that Ukraine finds least acceptable, such as the requirement for constitutional reform and passing legislation that grants special status to certain areas of the Donetsk and Luhansk regions.

Third, the incoming administration of President-elect Joe Biden will almost certainly expand U.S. assistance to Ukraine and encourage Kiev to take a hard line in the multilateral Normandy talks and in its bilateral negotiations with Russia. This does not exclude the possibility of making progress on stabilizing the situation in eastern Ukraine, but such developments would likely remain limited in scope and would not lead to an overall “reset” of relations between Moscow and Kiev.

EU no longer a pragmatic colleague

Elena Chernenko, Special correspondent for Kommersant and member of the board of the Council on Foreign and Defense Policy

Although relations between Russia and the EU seemed to be improving at one point this year, they have since deteriorated mainly due to the poisoning of Alexey Navalny. The EU decided that the Russian authorities were responsible for this incident and imposed sanctions on allies of Vladimir Putin. This move left the Kremlin frustrated because no evidence was presented showing how some of the high-placed individuals sanctioned were connected with the poisoning of the opposition leader.

In any case, Moscow increasingly views the EU as a punitive body. There is a growing sense in Russia that the sanctions will remain in place for a very long time. Moscow first came to this conclusion after the sanctions imposed over the Kerch Strait incident (Russian coast guard fired upon and captured three Ukrainian Navy vessels) were not relaxed or lifted, even after Russia released the Ukrainian sailors who had been detained and handed over their vessels.

This growing negativity, coupled with the absence of anything especially positive, prompted Foreign Minister Sergei Lavrov to strongly criticize the EU in a recent speech.

In 2021, EU-Russian relations will remain static or possibly deteriorate if the West — which will once again become a united front with President-elect Joe Biden in the White House — starts pressuring Moscow on human rights or elbowing its way into post-Soviet space.

Turkey emerges as a partner and a challenger to Russia

Marianna Belenkaya, Middle East correspondent for the Russian daily Kommersant

One of the main tasks for Russia in the Middle East will be to preserve the system of regional ties that it has acquired and built over the five years of its military campaign in Syria. At the same time, Moscow needs to avoid becoming even more dependent on regional players.

This primarily concerns Turkey. Over the past year, the partnership between Moscow and Ankara has expanded from Syria to Libya, and then to Nagorno-Karabakh. Now, however, the price for maintaining these bilateral relations has grown too high.

Although the Libyan settlement is simply a bonus for Russia’s foreign policy — if it works out, great, and if it doesn’t, no great problem — any mistake in the Caucasus, a traditional zone of Russia’s interests, could lead to serious economic and geostrategic losses.

At the same time, it is unclear just how much leverage Russia wields over Turkey. A major question remains as to whether Ankara is more dependent on Moscow for solving regional issues, or the other way around. Still, Russia can relax to some extent as long as Turkey’s relations with the EU and U.S. remain strained, and neither Brussels nor Washington has given a glimmer of hope on that front. What’s more, President-elect Joe Biden does not look favorably on Turkish leader Recep Tayyip Erdogan.

However, both Moscow and other regional players will be closely monitoring the Biden administration’s steps in the Greater Middle East, from Iran to Libya. For Russia, much will depend on whom the U.S. befriends in the region. Will some Middle Eastern countries seek a counterbalance to the U.S., or will Russia’s role in the region decline?

Of course, Syria will remain important. Washington and Brussels will probably become increasingly impatient with the “political downtime” there, especially in the run-up to the Syrian presidential elections planned for 2021. Moscow will focus on the policy of rebuilding Syria and strengthening Russia’s economic position in the country. This will inevitably deepen political tensions between the major players.

Russia and Latin America in 2021: It will be all about the vaccine

Vladimir Rouvinski, Professor at the Icesi University in Colombia

For Russia, 2020 in Latin America and the Caribbean was rather uneventful with a few exceptions. Rosneft was forced to depart from Venezuela following sanctions imposed by the United States, and all of the assets left to a company with no previous experience in the sector. Another important development was the return of left-wing governments in Argentina and Bolivia, both showing willingness to open the doors to a broader economic and political cooperation with the Kremlin.

In 2021, it is likely that the Russian allied regime in Caracas will keep power in Venezuela. Yet, the future of Russian investments here will remain uncertain because of the continuation of U.S. sanctions and no signs of a speedy recovery of the oil markets.

However, it will still be worth it to keep Venezuela, in addition to Argentina, Bolivia, Cuba, and Nicaragua on the list of Moscow’s friends. This is because 2021 will transform Latin America and the Caribbean, with a population of over 650 million people, into one of the biggest and lucrative world markets for the export of the Covid-19 vaccines.

At the same time, Russia will be watching very closely what the change in the U.S. presidency will bring to the Western hemisphere. Although it is doubtful that during Biden’s first year, Washington will take any sharp steps to influence the existing status-quos in the region, Moscow will look for the emergence of new trends in U.S.-Latin American relations and adjust its policy accordingly.

Relations with Africa in honeymoon phase

Olga Kulkova, Research Fellow at the Centre for Studies of Russian-African Relations and Foreign policy of African countries,

If this year has been a test of Russia’s deepening political, economic and cultural relations with Africa, it has been a test that Moscow passed with excellence.

Russia’s response to the coronavirus pandemic has confirmed its intention to build a genuine partnership with the African continent. More than 30 African states requested assistance from Russia in the fight against the new disease and Moscow has responded by providing, among other things, test systems, laboratory supplies, personal protective equipment, mobile laboratories and medical devices. Russia recently began shipping its Sputnik V coronavirus vaccine to the African continent.

After the first Russia-Africa Summit in 2019, the process of institutionalizing that partnership has continued. Thus, a new mechanism for maintaining regular dialogue, the Russia-Africa Partnership Forum with a secretariat as its parent body, was formed in 2020. The Association of Economic Cooperation with African States (AECAS) also began functioning and the second Russian-African Public Forum (RAOF) was held.

This process will gain momentum in 2021, when preparations will be underway for the Russia-Africa Summit in 2022 to be held in one of the African states. Concrete economic initiatives are being developed that are aimed at increasing the volume of Russian-African trade.

In a first, Russia and Sudan are preparing an agreement on the establishment of a material and technical support point for the Russian Navy on the Red Sea. This will strengthen Russia’s presence in Africa in 2021 and beyond and expand the fleet’s operational capabilities. Africa will be an important foreign policy priority for Russia in 2021 and the long-term prospects for the Russian-African partnership are good.

“No reset and no surrender” with Biden

Vladimir Frolov, political columnist and foreign policy expert

A new administration in Washington is usually greeted in Moscow with hopes for a fresh start. But this time around there is little expectation that the relationship will improve under Biden.

In Trump, Moscow is losing a U.S. president who personally wanted “to get along with Russia” despite obstruction from his own government. There will be no more of the “phone diplomacy” that advanced Russian interests through a warm personal rapport between the leaders.

Biden’s personal chemistry with Putin is already massively strained. Putin did not appreciate Biden’s unsolicited advice to him in 2011 not to return to the presidency.

Moscow is casting a shadow over the U.S. election by amplifying Trump’s claims of vote fraud to make the point that Biden has a legitimacy problem. This is signalling to Washington that the Kremlin will not accept any more democracy lectures.

Moscow’s strategy for dealing with the Biden administration will be “no reset and no surrender.”

Any talk of partnership is out. Adversarial rivalry and cost imposition will be the new normal. Countering U.S. capabilities to impact Russia’s sovereign decisions will be the utmost priority.

Russia will not be interested in a sustained engagement on issues of value with Washington while Russian demands are rejected or ignored. Nor will it acquiesce to U.S demands that Russia change its behavior first for Washington to reward it with a gesture of cooperation.

Whether Team Biden choses to pressure Russia to change its behavior or simply disincentivize any further disruptive action will be a key factor for Moscow. An early test will arrive when the new administration decides how to punish Russia for the Navalny poisoning under the 1991 CW Act. Another early test will be whether Biden rejects Putin’s initiative for the P5 “New Yalta” summit in favor of his own “Summit of Democracies.”

Moscow is not exactly thrilled with Biden’s national security team — incoming Intelligence Chief Avril Haines is under Russian sanctions — but harbours hope for at least getting coherent responses to Russian proposals. Nor does it like U.S. rhetoric on “rallying democracies against authoritarian kleptocracies” by the incoming National Security Advisor Jake Sullivan who personally holds Moscow responsible for interference in the 2016 election.

Moscow will resist efforts by Team Biden to support Kiev’s wish “to upgrade the Minsk agreement” by changing its implementation sequence. But it may entertain a credible plan that ties sanctions relief to flexibilities in Russia’s position, although Moscow is skeptical that Congress will oblige.

Nuclear arms control is one area where Russia expects real cooperation from Team Biden, with just days left to extend the New START Treaty.

China and Russia will come out of the pandemic storm stronger together

Alexander Gabuev, Senior fellow and chair of the Russia in Asia-Pacific Program at the Carnegie Moscow Center

Despite the global disruption caused by the COVID-2019 pandemic, Russia-China ties have remained stable and have actually improved in some important aspects.

Bilateral trade has dropped insignificantly as a result of the collapse in global oil prices. In 2021, however, the volume in trade is likely to compensate for this year’s losses and actually grow, as global vaccination may lead to rising oil prices and consumption. Russia is set to double its gas shipments to China to 10 bcm, and the two countries are eyeing a new gas contract in order to boost Beijing’s shift from coal to gas and renewables in the national energy sector.

In the political sphere, Vladimir Putin’s visit to China is now scheduled for summer 2021 and will end a nearly two year freeze on personal contact between the two sides, owed in part to the pandemic. The two sides are likely to prepare a hefty package of new deals and bilateral agreements during those talks.

However, the conversion of memorandums of understanding to flesh-and-blood cooperation remains uncertain, with one of the most important factors influencing it either way the policy choices of the new U.S. administration towards China and Russia both separately, and towards the emerging axis between the two.

Putin Stuck with Lukashenko in 2021

Nigel Gould-Davies, Senior Fellow for Russia and Eurasia at the IISS think tank

Two goals will drive Russia’s response to the mass mobilization for democratic change in Belarus: one geopolitical and one ideological. The geopolitical goal is to prevent Belarus — which borders three EU and NATO member states and Ukraine, as well as Russia — from developing a closer relationship with the West. The ideological goal is to prevent the peaceful overthrow of an eastern Slavic authoritarian regime – a threatening precedent for the Kremlin. For both reasons, Russia will work to prevent the Belarusian movement for democratic change from succeeding. How will it do so?

Russia now pursues its goals by supporting Alexander Lukashenko’s regime, and is likely to continue doing so. The best feasible outcome for the Kremlin is the regime’s suppression of peaceful change in ways that alienate it completely from the West. This would make Belarus less able than ever to resist Putin’s long-standing goal of integrating it into a de facto Union State dominated by Russia.

Could Russia find an authoritarian, but more pliant, alternative to Lukashenko? Even if it could engineer such change — which is doubtful — any future leader of Belarus would now need to win a genuinely free election to enjoy popular legitimacy. Russia might appear strong, but it faces limited choices. No love is lost between Putin and Lukashenko. But the two are locked in a toxic embrace. Neither has any alternative to the other.

Russia further plants flag in the Arctic

Elizabeth Buchanan, Lecturer in Strategic Studies with Deakin University at the Australian War College

2021 will see Moscow assume the Chairmanship of the Arctic Council, the region's governance body.

With this, Russia further legitimizes its Arctic credentials and steps into a stewardship role.

However, we need to be mindful of the bandwidth available within the Arctic Council and reorientate our expectations of a Russian chairmanship accordingly. The body is not mandated to consider geostrategic concerns in the region, although it is likely that Russia will suggest a new regional institution or informal forum through which military-security challenges can be dealt between the Arctic stakeholders.

The Russian domestic agenda for the Russian Arctic zone — over 50% of all the Arctic — will be impressive. 2021 will solidify key steps in the implementation and realization of an unprecedented era of Russian Arctic industrialization, which might provoke ill-conceived international suspicions of potential Russian expansion further north.

New foreign partnerships also will continue to emerge. Russian cooperation and collaboration with international partners in energy ventures will become even more apparent and will hopefully discredit talk of regional conflict and a looming Arctic war. As the Arctic becomes more important to Russia, any conflict would simply be bad for business and catastrophic for the Kremlin’s national security

As the Arctic heats up, I will be watching the depths of Putin’s newfound interest in climate change. Not only does this provide a potential avenue for Russia-U.S collaboration in the Biden-era, it also presents a viable opportunity for Russian leadership in the region.

A Message from The Moscow Times:

Dear readers,

We are facing unprecedented challenges. Russia's Prosecutor General's Office has designated The Moscow Times as an "undesirable" organization, criminalizing our work and putting our staff at risk of prosecution. This follows our earlier unjust labeling as a "foreign agent."

These actions are direct attempts to silence independent journalism in Russia. The authorities claim our work "discredits the decisions of the Russian leadership." We see things differently: we strive to provide accurate, unbiased reporting on Russia.

We, the journalists of The Moscow Times, refuse to be silenced. But to continue our work, we need your help.

Your support, no matter how small, makes a world of difference. If you can, please support us monthly starting from just $2. It's quick to set up, and every contribution makes a significant impact.

By supporting The Moscow Times, you're defending open, independent journalism in the face of repression. Thank you for standing with us.

Remind me later.