A whirlwind two weeks of post-election violence and fierce power struggles in Kyrgyzstan has political observers at odds over Russia’s role and true intentions in Central Asia’s “island of democracy.”

Anger over pro-government parties’ gains in an Oct. 4 parliamentary vote spilled into the streets of Bishkek, prompting the fall of the government and resignation of president Sooronbay Jeenbekov on Thursday.

Twelve days after the start of Kyrgyzstan’s third revolution in 15 years, populist former lawmaker Sadyr Japarov, who was freed from jail during the protests, has claimed the roles of both president and prime minister.

Analysts interviewed by The Moscow Times said they believe any new Kyrgyz political regime will be inherently pro-Russian and look to Moscow for conflict resolution.

“Today, Russia is making efforts to stabilize the situation with the pro-Russian Kyrgyz leaders popular among the people,” said Baktybek Beshimov, a former Kyrgyz lawmaker who is now a professor at Northeastern University’s Global Studies and International Relations program.

Kyrgyzstan’s former president claimed to have had multiple phone conversations with Russian President Vladimir Putin during the crisis, while Japarov stressed Russia’s role as Bishkek’s strategic partner during his ascent to power.

What analysts disagree on is whether Russia is playing a constructive role in the ex-Soviet country, where it deploys an airbase and relies on a large pool of labor migrants.

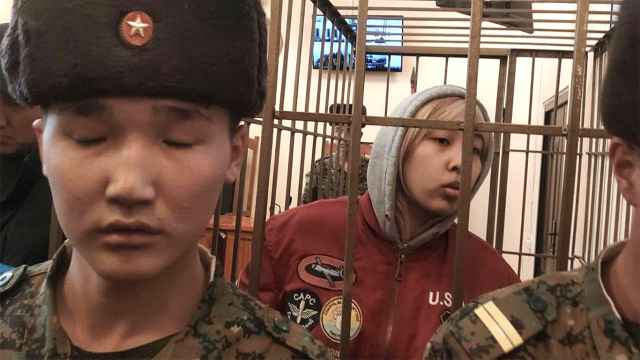

Japarov’s supporters freed him from jail amid the post-election protests and used street demonstrations to install him in power. The nationalist former lawmaker had been serving an 11.5-year sentence on charges of kidnapping he says were politically motivated.

The Kremlin has openly sided with neither Japarov nor Jeenbekov, instead stressing the need for stability. For Beshimov, this lack of vocal support signals that Putin “does not believe in Jeenbekov.”

“Putin has been forced to find a solution without failed Kyrgyz leaders,” said Beshimov.

Dr. Erica Marat, who heads the Regional and Analytical Studies department at the U.S. Department of Defense-run National Defense University’s College of International Security Affairs, agreed that Putin’s silence effectively hastened Jeenbekov’s resignation.

“Japarov was emboldened in his calls for Jeenbekov’s resignation after meeting with [Russia’s deputy prime minister for post-Soviet integration Dmitry] Kozak,” Marat said.

What Monday’s three-way meeting between Japarov, Jeenbekov and Kozak signaled, however, is that “Russia is interested in undermining hopes for an orderly and legitimate transition of power through another parliamentary election,” she said.

“A more centralized political system in Kyrgyzstan is preferred in Moscow,” said Marat.

While it’s true that Russia keeps lines of communication open with competing figures who often travel to Moscow for consultation, Kyrgyz human rights activist Dinara Oshurakhunova said “you can’t simply say that Kremlin proteges came to power.”

“The Kremlin is in no rush to show its support for a specific group,” said Oshurakhunova, who heads the Bishkek-based Civic Initiatives Public Foundation and coordinates the Civic Control Committee.

“It’s a welcome development because outside interference is unacceptable in the current situation,” she added, warning that “we’ll be forced to call on foreign powers to intervene ourselves if there’s a violent escalation.”

Ordinary citizens who took part in the post-election protests appear to have no illusions about Russia’s outsize influence in Kyrgyzstan’s political gamesmanship.

Logistics entrepreneur Abdimital Jumabekov, who rallied against the Oct. 4 election results, put it bluntly: “The president will be whoever gets approval from Putin.”

“He has so many levers,” Jumabekov told The Moscow Times hours after witnessing the storming of the seat of government in the early hours of Oct. 6.

Independent Central Asia analyst Arkady Dubnov agreed with that take “for both the better and the worse.”

“For the better, because a single powerhouse is needed to avoid bloodshed,” he said.

“For the worse, because it means that Kyrgyz [political] elites still haven’t reached the point of understanding that would allow them to maintain the balance [of power].”

A Message from The Moscow Times:

Dear readers,

We are facing unprecedented challenges. Russia's Prosecutor General's Office has designated The Moscow Times as an "undesirable" organization, criminalizing our work and putting our staff at risk of prosecution. This follows our earlier unjust labeling as a "foreign agent."

These actions are direct attempts to silence independent journalism in Russia. The authorities claim our work "discredits the decisions of the Russian leadership." We see things differently: we strive to provide accurate, unbiased reporting on Russia.

We, the journalists of The Moscow Times, refuse to be silenced. But to continue our work, we need your help.

Your support, no matter how small, makes a world of difference. If you can, please support us monthly starting from just $2. It's quick to set up, and every contribution makes a significant impact.

By supporting The Moscow Times, you're defending open, independent journalism in the face of repression. Thank you for standing with us.

Remind me later.