Much has been made of Russia’s pivot to China as a danger to the U.S.-led world order, and the Kremlin has done its best to play up these fears in an effort to keep Russia punching above its weight. In reality, though, Russia has pivoted more successfully toward the Middle East, where President Vladimir Putin feels at home among a particular cohort of authoritarian rulers.

Last week’s annual session of the Valdai Discussion Club, Putin’s favorite platform for airing foreign policy ideas, was dedicated to “The Dawn of the East and the World Political Order.” The intellectual debate centered, of course, on China and Russia’s strategic relationship to it. But the underlying problem there is that Russia doesn’t have enough to offer China economically to be considered an equal partner. Russia can be a major energy supplier; it can also provide its vast territory and use its strength in the Arctic to build transport corridors for Chinese trade. There are, however, competing options for China. Besides, Russia isn’t an irreplaceable market for Chinese goods, and it doesn’t have much valuable technology to transfer.

That raises the question of how Russia can leverage its military might, its one major advantage as a global power, to make a partnership with China more equal. And that’s where Russia’s Middle Eastern strategy comes in. In a contribution for the Valdai Club, foreign policy expert Timofei Bordachev wrote: "There is little doubt that Russia will remain a predominantly military power in keeping with the pattern formed by its history. This runs in the blood and is part of its bedrock national tradition. Besides, the projection of Russian military capabilities in the Middle East has demonstrated the need for and efficiency of “hard power” for successful diplomatic manipulation."

In his speech at the Valdai Club session in Sochi last week, Putin addressed the Middle East before discussing Russia’s economic ties with China and other Asian countries. He bragged about Russia’s military success in Syria (which is indisputable) and its subsequent diplomatic victories (which are less obvious).

Putin said: "We have managed to launch a political process inside Syria by establishing close working relationships with Iran, Turkey, Israel, Saudi Arabia, Jordan, other Middle Eastern countries and the United States. Esteemed colleagues, you’ll have to agree that such a complex diplomatic setup with very different states that have very different emotions toward each other was hard to imagine just a few years ago. But now it’s a fact, we have managed it."

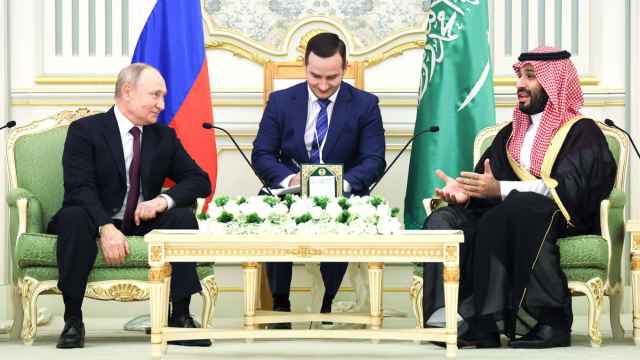

There is some truth to the boast. Russia has used the Syrian conflict and other opportunities to build relationships with leaders who can’t stand each other. Putin is on a friendly footing with Turkish President Recep Tayyip Erdogan and Syrian dictator Bashar al-Assad, as well as Iranian President Hassan Rouhani and Saudi Crown Prince Mohammed bin Salman.

He also has good relationships with the region’s other key figures, including Benjamin Netanyahu, who is still Israel’s prime minister despite a humbling election last month, and with Egyptian leader Abdel-Fattah El-Sisi. King Abdullah II of Jordan was Putin’s guest at the Valdai Club meeting.

Putin used different means to secure these relationships. He went to war for Assad and called Erdogan to offer support during a 2016 coup attempt. (The U.S. opted not to do the same, which probably explains Erdogan’s decision to buy Russian-made S-400 antimissile systems despite U.S. protests.) He ignored the backlash against Prince Mohammed for his apparent involvement in the killing of the journalist Jamal Khashoggi. Breaking with longstanding practice, he has also worked with the Saudis to set an oil price acceptable to both. He backed the Iranians when the U.S. hit them with sanctions. He didn’t let that alliance get in the way of constructive conversations with Netanyahu on keeping Israel from being attacked from Syrian territory.

All these cases have one thing in common, though: In each, Putin backed the status quo. Like the Russian czars of old, who saw it as their goal to support monarchies everywhere, he is a consistent opponent of regime change and backer of incumbents. The one exception — Russia’s unofficial backing of Libyan general Khalifa Haftar, who is fighting his country’s United Nations-recognized government — doesn’t negate the rule: It can be argued that Haftar is the incumbent in Libya since he controls more territory than the government.

Such a record endears Middle Eastern leaders to Putin: They can be reasonably certain he won’t pull a fast one on them. With the U.S. they can’t be so sure, since Washington has backed or directly performed several regime changes in the region.

Nor can anyone be certain that the U.S. will back its allies as consistently as Putin has backed his. In Syria, the U.S. has long supported the Kurdish-led Syrian Democratic Forces — but as announced on Monday, the U.S. is pulling back from the areas held by the Kurds to clear the way for a long-planned Turkish offensive.

On a certain level, the Russian support of incumbents regardless of their reputations, and of what they do to their own people, is a demonstration of Moscow’s usefulness to China and other Asian countries. Putin’s other guests at the Valdai Club session included presidents Ilham Aliyev of Azerbaijan and Rodrigo Duterte of the Philippines — both strongmen who value Putin’s backing.

China, which has spent decades cultivating business projects in Africa, may on occasion need Russia’s willingness to use force on incumbents’ behalf. In Venezuela, Russia’s backing of President Nicolas Maduro also protects Chinese investments in the regime.

But the Middle East is not just Putin’s showroom for China’s benefit. It’s a region where he’s uniquely suited to playing politics. His interlocutors there are people who run their countries in a similar style, and most of them, like Putin, are in charge of commodity-based economies. The Russian leader blends right in — he can even quote the Koran with the best of them.

Putin’s Russia is not really a European, a Central Asian or an East Asian country, as its geography might suggest. It’s a Middle Eastern authoritarian regime. Its pivot to the Middle East is more natural than previous attempts to cozy up to the U.S. or the current overtures to China. Whether it’s in Russian national interests is a question for Putin’s successors to ponder.

This article first appeared in Bloomberg.

A Message from The Moscow Times:

Dear readers,

We are facing unprecedented challenges. Russia's Prosecutor General's Office has designated The Moscow Times as an "undesirable" organization, criminalizing our work and putting our staff at risk of prosecution. This follows our earlier unjust labeling as a "foreign agent."

These actions are direct attempts to silence independent journalism in Russia. The authorities claim our work "discredits the decisions of the Russian leadership." We see things differently: we strive to provide accurate, unbiased reporting on Russia.

We, the journalists of The Moscow Times, refuse to be silenced. But to continue our work, we need your help.

Your support, no matter how small, makes a world of difference. If you can, please support us monthly starting from just $2. It's quick to set up, and every contribution makes a significant impact.

By supporting The Moscow Times, you're defending open, independent journalism in the face of repression. Thank you for standing with us.

Remind me later.