If all goes to plan for St. Petersburg’s new governor, Russia’s second-largest city may soon have the landscaped public parks, brand-new buses and budget surpluses of its big brother Moscow.

The man behind the promises, Kremlin protégé Alexander Beglov, was inaugurated Wednesday in the gold and marble halls of the Mariinsky Palace in the city center, surrounded by its most illustrious denizens.

But naysayers claim that to secure Beglov’s pledges St. Petersburg may also have copied Moscow in a less noble fashion: by conducting elections in a way that many see as fraudulent.

“Everyone saw that these were not elections but an appointment. Beglov will now have a hard time saying that he was chosen by the people,” said political analyst Grigory Golosov.

While Beglov won 64% of the gubernatorial vote in the Sept. 8 poll, observers say the election was among the dirtiest in recent years — marked by ballot stuffing and intimidation of opponents. Critics are now refusing to recognize the authority of a man they claim is an incompetent stooge sent from Moscow.

Who is Mr. Beglov?

Beglov was always going to be a hard sell to Russia’s most Europeanized city.

Conspicuously religious and conservative, the 63-year-old aide to President Vladimir Putin is prone to bumbling his words in public appearances and issuing alarmist warnings that many say veer on paranoia.

In a March 2018 speech calling for St. Petersburg students to re-elect Putin he warned against the dangers of mind control by enemies from abroad and said Russia’s key strategic goal should be to develop new nuclear weapons. Seven months later, the Russian president appointed Beglov as interim governor of St. Petersburg.

Political scientists said it’s hard to characterize Beglov as a politician, because he never was one, and has only ever served as an administrator.

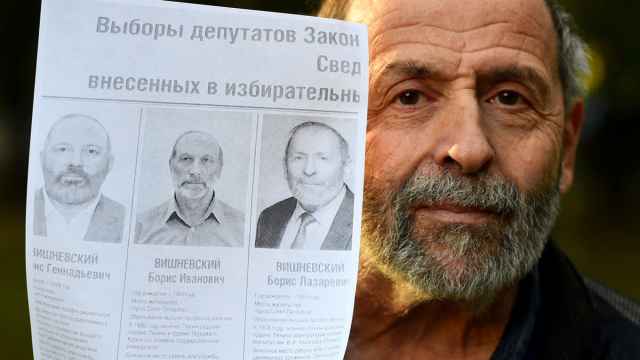

“He’s a bureaucrat, who, until this election, has never had to speak publicly and has never been elected to office,” said Boris Vishnevsky, an opposition deputy from the liberal Yabloko party in St. Petersburg, and a prominent Beglov critic who was denied the chance to run in the gubernatorial election.

“In this way, he’s a typical Putin appointee of recent years,” he added.

Shortly after being appointed interim governor, Beglov failed in his first major test as an administrator: preparing the city for the most basic of challenges in Russia — snow.

Between January and mid-March, nearly 4,000 St. Petersburgers were injured after slipping on sidewalks that hadn’t been cleared of ice, while razor-sharp icicles falling from roofs killed one and injured dozens.

The debacle led to a public outcry that tarnished Beglov’s image. In response, the interim governor’s PR team organized several photo-ops: Beglov handing out snow shovels to senior city officials and escorting a woman he had reportedly rescued from the ruins of a collapsed building. She later told journalists he had only taken her arm for the picture. Both were seen as cheap PR stunts by a skeptical public.

Surveillance and smear campaigns

Russian media accused Yevgeniy Prigozhin, the man behind Russia’s infamous troll factory, and a media magnate with close ties to the Kremlin, of joining Beglov’s PR campaign in the run-up to the gubernatorial elections in September.

Soon after, opposition activists reported being harassed and followed by men with cameras and several opposition politicians were targeted in smear campaigns.

One such lawmaker was Maxim Reznik, a fiery opposition deputy in St. Petersburg’s Legislative Assembly who publicly criticized Beglov in January, saying he was unworthy to run as governor. Months later, dozens of articles came out in pro-government media, calling Reznik a marijuana smoker with ties to Western intelligence.

Reznik says he and others from both the ruling United Russia party and opposition were subject to slezhka (surveillance) and travlya (public smear campaigns).

“They targeted those who either didn’t agree with Beglov or who acted against him,” Reznik said.

Meanwhile, Beglov’s opponents for the position of governor were either barred — like Vishnevsky from Yabloko — or dropped out of the race themselves — like nationalist Liberal Democratic Party (LDPR) candidate Oleg Kapitanov and Communist Party candidate Vladimir Bortko.

Bortko withdrew his candidacy a week before the gubernatorial election after reportedly meeting with a member of Putin’s presidential administration—paving the way for Beglov to win an outright majority in the first round.

On election day itself, monitoring groups noted mass violations, including the removal and harassment of dozens of independent observers, physical attacks, the disappearance of hundreds of ballots and a massive spike in votes near the end of the day.

“The turnout was exceptionally low, even by official figures, it was 10% lower than in the last elections for governor, and even that is doubtful due to the much-publicized jump in turnout in the last hours before polls closed,” said analyst Golosov.

Not our governor

Vishnevsky, the opposition politician who was barred from running against Beglov, said he and his supporters won’t recognize the results of the election, which he called a “sham.”

“We don’t view Beglov as the elected governor of St. Petersburg, and in this respect, we don’t recognize the elections. He was reappointed to this role in a procedure that for some reason was called an election,” he said.

In protest, Vishnevsky and other opposition leaders including Reznik led a rally on Tuesday, the day before Beglov’s inauguration.

On St. Petersburg’s windswept and rainswept Lenin Square, a few hundred protesters carried posters with slogans saying, “Stop lying to us” and, “I have a right to choose.”

“I’m furious after what I saw as an observer at the election,” said Ksenia, 30, a protester and first-time election observer.

“There were too few of us at the polling station so we couldn’t stop all of the violations but what we saw was astounding,” she said.

Election season is over; so don’t expect money from Moscow

If there’s one thing that Beglov does have, it’s the Kremlin’s backing.

After thanking voters during his inauguration speech Wednesday, Beglov issued a statement thanking Putin for his support and said he was proud that “St. Petersburg is back on the federal agenda.”

In the run-up to the election, Beglov secured billions of rubles in funding from the federal government for infrastructure development in St. Petersburg in line with Putin’s $400 billion six-year National Projects spending program.

“The amount of financing secured from the federal center in Moscow over the past year was unprecedented and grandiose by St. Petersburg standards,” said Golosov.

Together with Putin, Beglov unveiled plans last April for a giant public park on the embankment in the city center to rival Moscow’s Zaryadye Park.

Taking Moscow’s cue, he has also promised to make St. Petersburg a “social, comfortable, smart and open city,” with increased digitization and transparency.

Golosov, however, said it is unlikely that St. Petersburg will catch up to Moscow because the capital’s annual budget is four times bigger — at around 2.7 trillion rubles ($42.2 billion) compared to St. Petersburg’s 644 billion rubles ($10.1 billion).

He added that Beglov’s political capital in the Kremlin is unlikely to continue bringing added investment because “the federal center no longer has any reason to invest large sums in St. Petersburg after the election season.”

“Now we will see how Beglov will act as governor under normal conditions, without benefits [from Moscow].

While Beglov has promised to make his administration transparent to citizens, the new governor has already shown himself to be publicity shy.

At the end of his inauguration ceremony at the palace he left through the back door — presumably to avoid journalists who had been relegated to a side room during the proceedings.

Government critics like Vishnevsky fear this is a sign of things to come.

“A politician must fight for the trust of the electorate, but a bureaucrat must only fight for the trust of his higher-ups,” he said.

A Message from The Moscow Times:

Dear readers,

We are facing unprecedented challenges. Russia's Prosecutor General's Office has designated The Moscow Times as an "undesirable" organization, criminalizing our work and putting our staff at risk of prosecution. This follows our earlier unjust labeling as a "foreign agent."

These actions are direct attempts to silence independent journalism in Russia. The authorities claim our work "discredits the decisions of the Russian leadership." We see things differently: we strive to provide accurate, unbiased reporting on Russia.

We, the journalists of The Moscow Times, refuse to be silenced. But to continue our work, we need your help.

Your support, no matter how small, makes a world of difference. If you can, please support us monthly starting from just $2. It's quick to set up, and every contribution makes a significant impact.

By supporting The Moscow Times, you're defending open, independent journalism in the face of repression. Thank you for standing with us.

Remind me later.