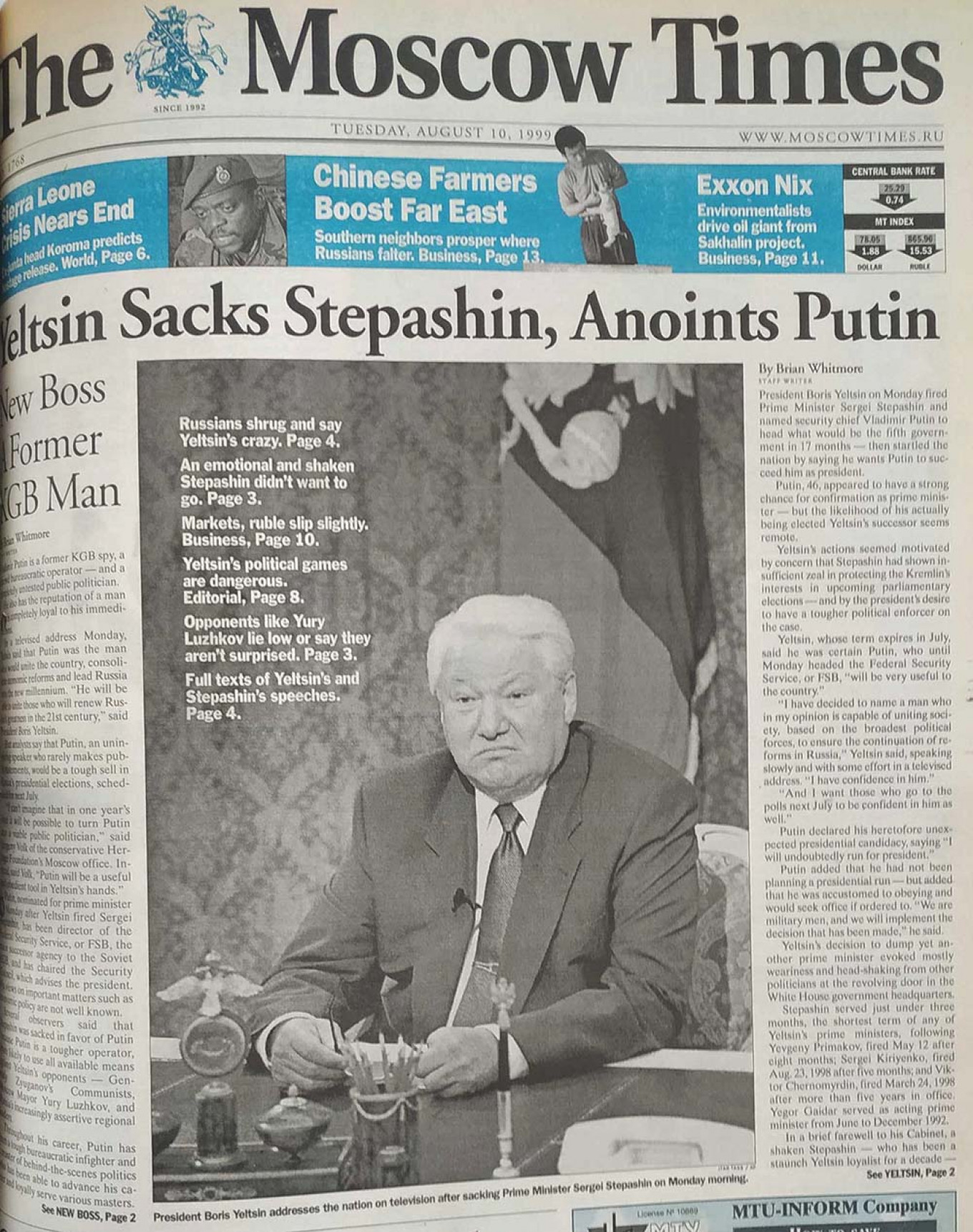

On this day 20 years ago, Russian President Boris Yeltsin named Vladimir Putin the country's acting prime minister and successor for the presidency.

At the time, most Russians knew little about the 46-year-old head of the Federal Security Service (FSB), who had largely kept out of the public eye.

The Kremlin's political opponents, meanwhile, criticized Yeltsin's move, citing Putin's lack of political experience and his ties to the security forces.

Some observers even predicted that he would fail to win the upcoming presidential elections.

Yet since then, Putin has cemented his position at the top of Russian politics and has remained in power as either president or prime minister for two decades, presiding over an era of immense economic growth and dwindling political freedoms.

Here are excerpts of articles from The Moscow Times archive immediately after the Aug. 9, 1999 announcement:

President Draws Criticism From All Political Camps, Aug. 10, 1999

By Andrei Zolotov

President Boris Yeltsin took a beating across the political spectrum for his decision to trade in Sergei Stepashin for Vladimir Putin.

"This is an agony, a total insanity," Communist Party leader Gennady Zyuganov declared in a radio interview. "Who will take a prime minister seriously if they change them like gloves?'' [...]

Some of the most biting comments came from Boris Nemtsov, a former deputy prime minister and one of the leaders of the Right Cause bloc of "young reformers."

"It's hard to explain madness," Nemtsov said on Ekho Moskvy radio. "The people have grown tired of watching an ill leader who is not capable of doing his job." [...]

Yeltsin's brash announcement that Putin is his chosen successor provoked very little comment from politicians.

In part, it was explained by Duma speaker Gennady Seleznyov, who said that all those who had been named Yeltsin's heir apparent in the past were eventually fired.

Yeltsin has "put a cross on Putin's career," Seleznyov said.

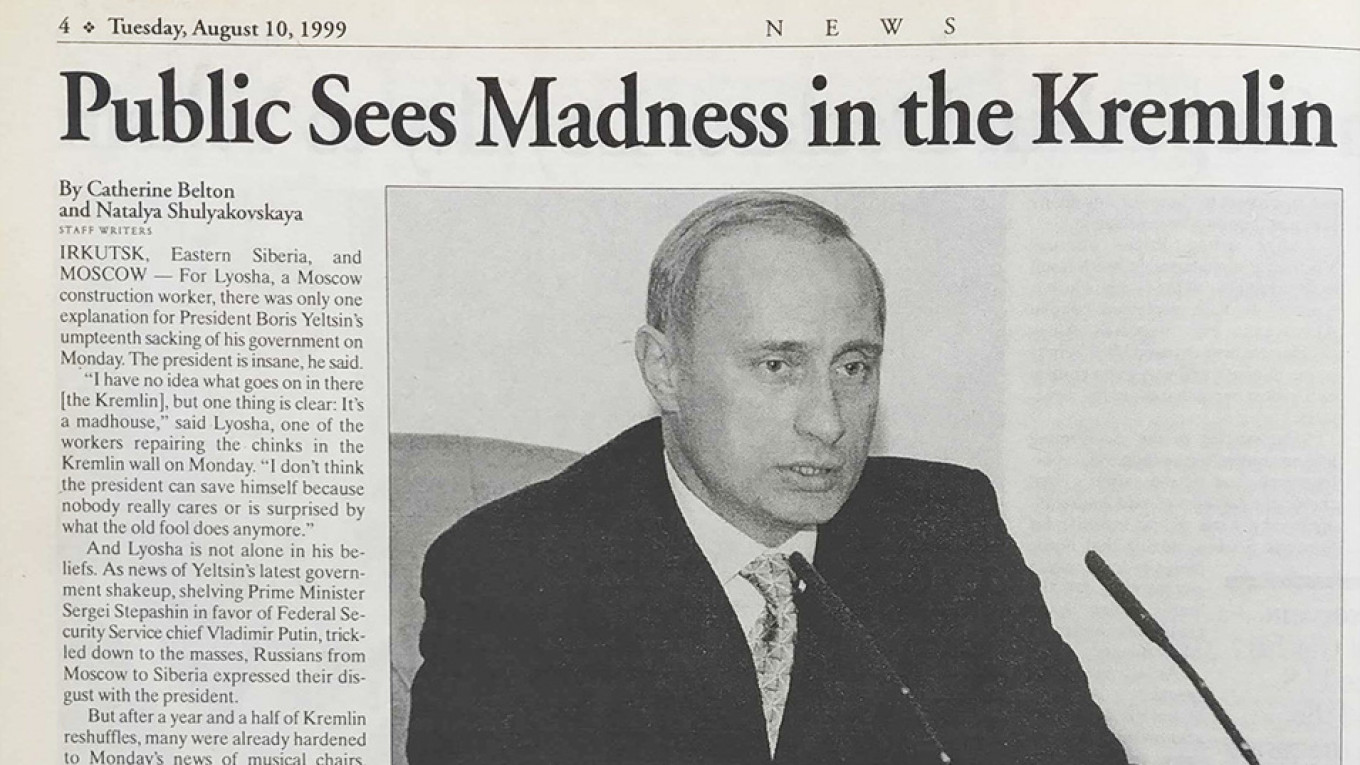

Public Sees Madness in the Kremlin, Aug. 10, 1999

By Natalya Shulyakovskaya and Catherine Belton

For Lyosha, a Moscow construction worker, there was only one explanation for President Boris Yeltsin's umpteenth sacking of his government on Monday. The president is insane, he said.

"I have no idea what goes on in there [the Kremlin], but one thing is clear: It's a madhouse," said Lyosha, one of the workers repairing the chinks in the Kremlin wall on Monday. [...]

As news of Yeltsin's latest government shakeup, shelving Prime Minister Sergei Stepashin in favor of Federal Security Service chief Vladimir Putin, trickled down to the masses, Russians from Moscow to Siberia expressed their disgust with the president. [...]

Like many of his military buddies, [retired lieutenant colonel] Timoshenko keeps hoping for a strong figure to take over and restore order to the country.

"We always hope for a [Augusto] Pinochet, but Putin is no Pinochet," Timoshenko said glumly. [...]

For Timoshenko and his army friends, Putin may not be the Pinochet they are waiting for. But for many Russians, the behind-the-scenes player did not register much of a reaction at all.

"Who did you say Putin was?" asked Zhenya Molchanova, a hot dog seller in Alexandrovsky Sad. "I knew Stepashin, but I've never heard of Putin."

It is not surprising that Putin - a former KGB spy in Germany - is little known to a broader audience. He rarely appears on television, and his skills at pulling political strings while staying hidden from public view have earned him a reputation as Russia's "grey cardinal."

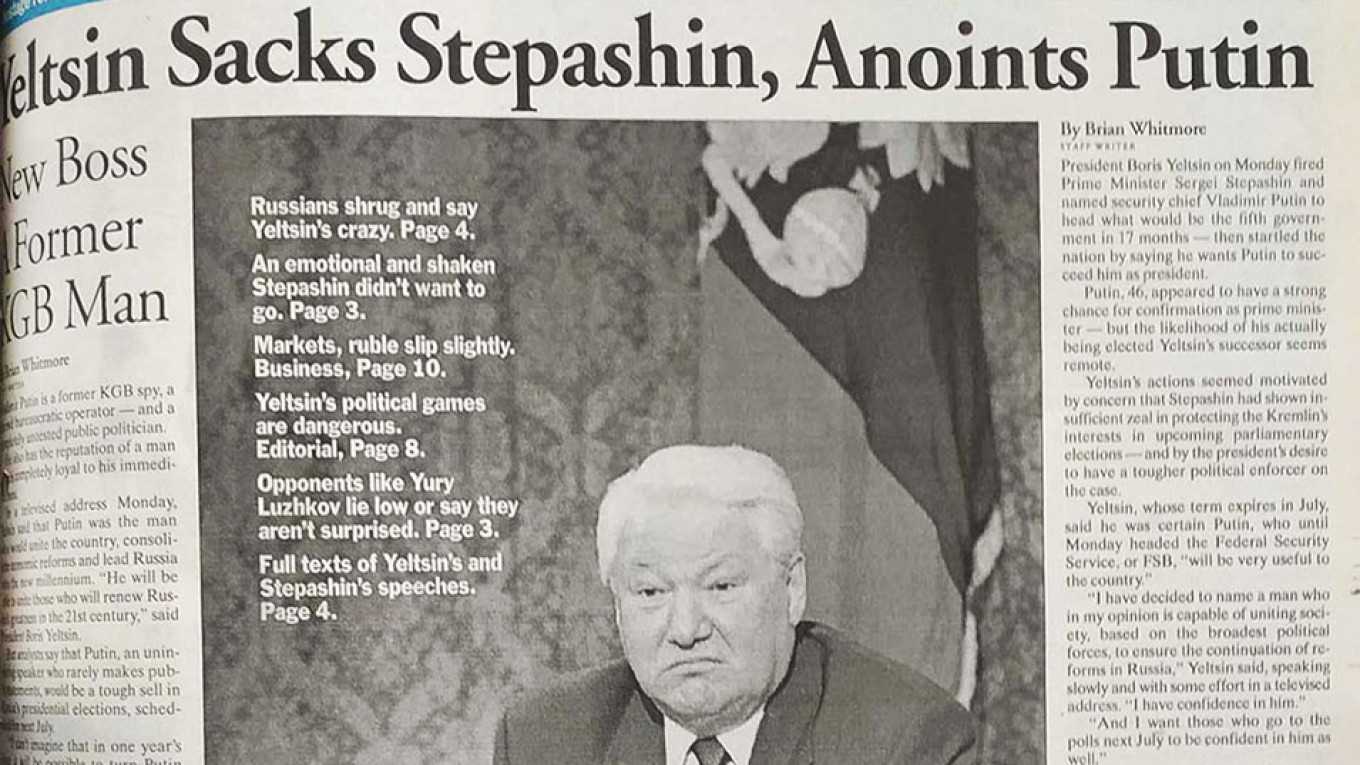

New Boss A Former KGB Man, Aug. 10, 1999

By Brian Whitmore

Vladimir Putin is a former KGB spy, a shrewd bureaucratic operator - and a completely untested public politician.

He also has the reputation of a man who is completely loyal to his immediate boss.

In a televised address Monday, Yeltsin said that Putin was the man who would unite the country, consolidate economic reforms and lead Russia into the new millennium. "He will be able to unite those who will renew Russia's greatness in the 21st century," said President Boris Yeltsin.

But analysts say that Putin, an uninspiring speaker who rarely makes public statements, would be a tough sell in Russia's presidential elections, scheduled for next July.

"I can't imagine that in one year's time it will be possible to turn Putin into a viable public politician," said Yevgeny Volk of the conservative Heritage Foundation's Moscow office.

Russia Awaits New Ruler Of Oligarchs, Aug. 10, 1999

By Yulia Latynina

Monday morning, it finally became clear who will not become Russia's president in the year 2000. It will not be Vladimir Putin. […]

The only thing worse for Putin [than Yeltsin's appointment] would be an endorsement from a Russian lesbian association.

The astonishing fact that President Boris Yeltsin seriously considers himself capable of appointing his successor shows how little the president understands the political reality. Any nomination from him would inevitably cause a serious allergic reaction in the voters.

The only thing worse for Putin would be an endorsement from a Russian lesbian association.

Russia does not elect a president. Russia elects a super-oligarch, who will first of all devour his forefathers. And the forefathers are panicking.

Wary Duma Expects To Confirm Putin Fast, Aug. 11, 1999

By Melissa Akin

"Putin, Rasputin - it doesn't matter," Pribylovsky said. "The main thing is to go into elections with an office, a telephone and a fax."

Putin is seen as a tougher manager than his predecessor, who reportedly refused to go along with Kremlin schemes to manipulate elections.

Viktor Ilyukhin, the leader of the Duma's radical left wing, said he feared Putin could take unconstitutional decisions such as canceling elections.

"It scares me already," Ilyukhin said in a telephone interview.

Papers: President's Acts Protect His Inner Circle, Aug. 11, 1999

By Adam Tanner

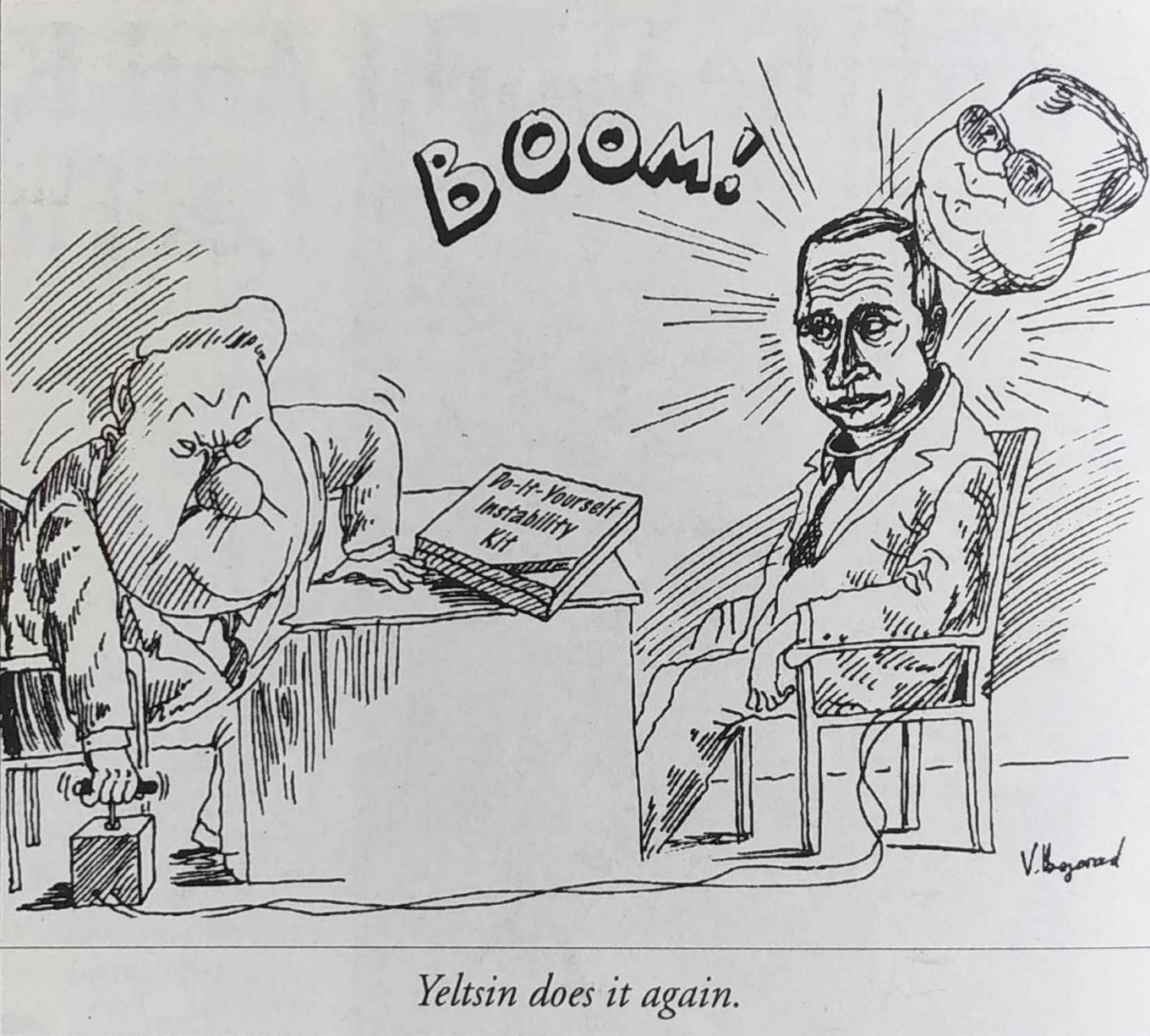

Russian newspapers agreed Tuesday that President Boris Yeltsin's sudden firing of Prime Minister Sergei Stepashin was motivated by his own selfish interests rather than concern about improving Russia's plight.

Some newspapers saw Yeltsin's motivation in naming Vladimir Putin as prime minister and his preferred candidate for president as a desire to protect his inner circle of Kremlin advisers — called "the family" — from prosecution after his term ends next year.

"Fired because of family complications" was the top headline in the daily Segodnya. [...]

The [Noviye Izvestia] daily showed a cartoon of Yeltsin placing a crown on a puppet Putin and declaring him Russia's president. [...]

A Message from The Moscow Times:

Dear readers,

We are facing unprecedented challenges. Russia's Prosecutor General's Office has designated The Moscow Times as an "undesirable" organization, criminalizing our work and putting our staff at risk of prosecution. This follows our earlier unjust labeling as a "foreign agent."

These actions are direct attempts to silence independent journalism in Russia. The authorities claim our work "discredits the decisions of the Russian leadership." We see things differently: we strive to provide accurate, unbiased reporting on Russia.

We, the journalists of The Moscow Times, refuse to be silenced. But to continue our work, we need your help.

Your support, no matter how small, makes a world of difference. If you can, please support us monthly starting from just $2. It's quick to set up, and every contribution makes a significant impact.

By supporting The Moscow Times, you're defending open, independent journalism in the face of repression. Thank you for standing with us.

Remind me later.