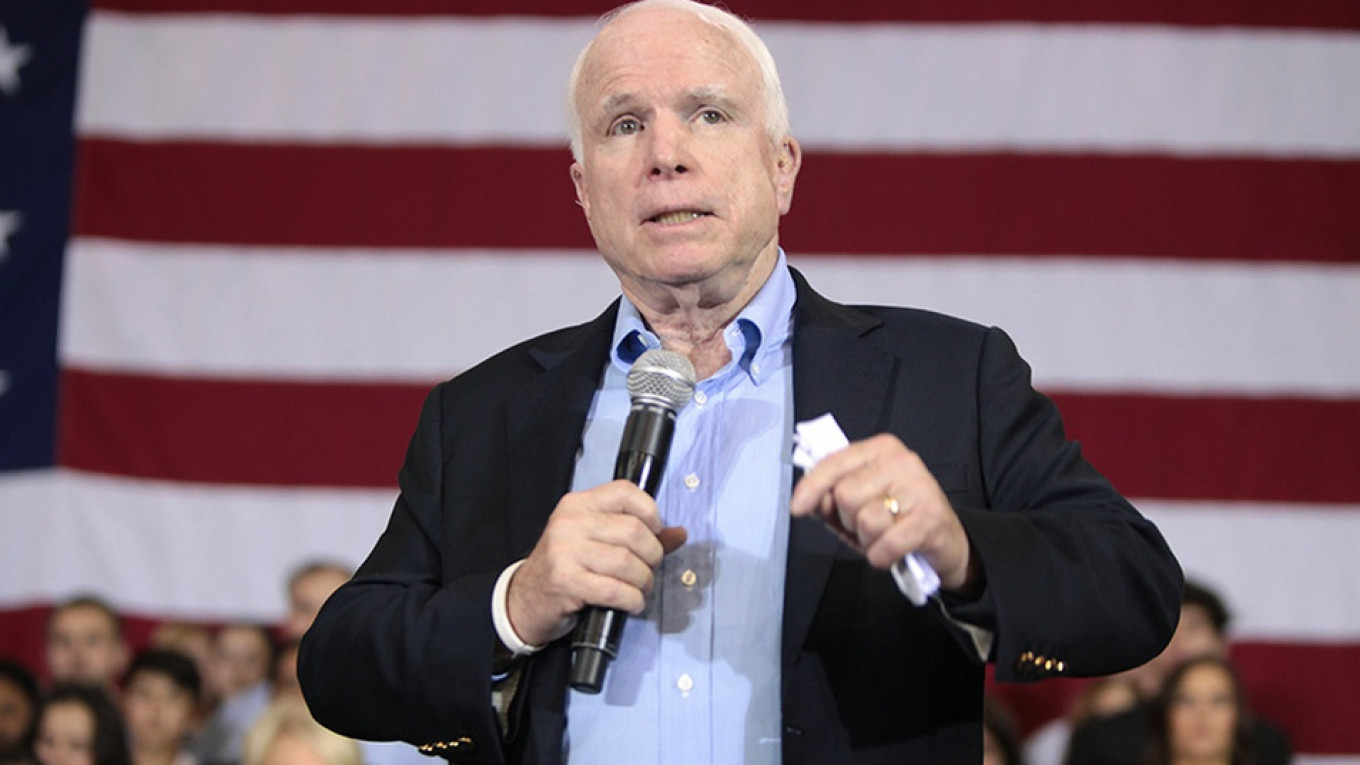

Senator John McCain, who died on Saturday, is being eulogized not just in the U.S. but also throughout Eastern Europe, in Ukraine and in Georgia. Not in Russia, however, where establishment figures brand him an enemy even in death. The clarity of McCain’s stance on Russia will be missed by everyone, though, including Kremlin propagandists.

Polish Prime Minister Mateusz Morawiecki remembered McCain as “a proven friend of Poland” and a “tireless guardian of freedom and democracy.” Ukrainian President Petro Poroshenko mourned him as a “great friend of Ukraine” who had made an “invaluable contribution” to its democracy and freedom. Georgian President Giorgi Margvelashvili called him a “national hero of Georgia.” And former Estonian President Toomas Hendrik Ilves wrote in a heartfelt obituary: “In Eastern Europe, few know or care about John McCain’s domestic politics. Here, the late senator is a symbol of all that we thought was good about the U.S.: decency, a belief in liberty, human rights and a liberal world order.”

Commentary from Russians aligned with President Vladimir Putin’s regime presents a powerful contrast. The obituary by the official news agency RIA Novosti is titled “America’s Chief Russophobe.”

“Let God receive his dark soul and Himself determine its future,” wrote legislator Oleg Morozov.

“His only real ideology was, ‘Defend your own and bash the others,’” wrote Konstantin Kosachev, head of the foreign affairs committee in the upper house of Russia’s parliament. “Its mainstay was loyalty to America and American interests, not criteria of peace, good and justice.”

The sentiment behind both the eastern European and the Russian reactions to McCain’s death is understandable. In any regional matter, McCain always backed countries and politicians trying to break away from Russia’s orbit and bashed Putin and his allies. He took sides predictably and wholeheartedly. There was no nuance to his stance, no buts to his firm conviction that Russia, defeated in the Cold War by President Ronald Reagan’s firmness and reduced to “a gas station masquerading as a country,” deserved to keep losing as a revanchist authoritarian state.

Politicians working to distance their countries from a history of dependence on Russia could always count on McCain. He never let them down, even if the administrations of Presidents George W. Bush and Barack Obama never matched his zeal. Such reliability is rare in politics. But what it did in Moscow was feed a particular type of convenient confusion; the Putin regime needed an external enemy, the U.S. was a traditional one, and it wasn’t too much of a propaganda stretch to hold up McCain as the bearer of the true American attitude toward Russia. “He taught us better to understand ourselves and America,” Morozov wrote in his Facebook post on Sunday:

The most important thing McCain did was, essentially, to declare that Russia is incorrigible. No matter how we wanted to be liked, no matter how we bowed and swore devotion to the West, as we did throughout the ‘90s, we could never be good. We are enemies forever! That’s the logic of McCain, and it’s good in its transparency and consistency.

The problem with perfect consistency is that it ignores inconvenient facts. As McCain focused the America-hatred of the Putin elite, he kept Putin on his toes and always careful to coup-proof his regime. Meanwhile, he made mistakes that helped Putin score propaganda points – and, once, even wage a brief, victorious war.

After supporting Mikheil Saakashvili’s ascent to power in Georgia in a peaceful revolution in 2003, McCain stuck with his protege once he turned authoritarian. As he ran for president in 2008, McCain encouraged Saakashvili’s illusion of Western support, and was probably partly responsible for the Georgian leader’s rash decision to engage with Russia militarily in South Ossetia, a mountainous part of Georgia along Russia’s southern border. The Kremlin was waiting for that move to pounce, and within days, Georgia was overrun by Russian troops and in danger of losing its statehood. Subsequent Western non-interference taught Putin that he enjoyed a measure of immunity in Russia’s immediate neighborhood – a revelation that informed his risk-taking in Ukraine in 2014.

McCain’s approximate understanding of the intricacies of post-Soviet politics and power dynamics has probably weakened Putin’s opponents in Russia.

“Dear Vlad, the #ArabSpring is coming to a neighborhood near you,” he tweeted in December, 2001 – exactly the kind of support Russian protesters against the rigging of a parliamentary election didn’t need. To Putin, this was a sign that the Russian political opposition wasn’t just egged on, but was directly supported by the U.S. as it sought to overthrow him. This belief shaped Putin’s third presidential term, which began in 2012 and ended this year: The Kremlin steamrolled over the opposition and the liberal Russian media, uniting his core electorate around the idea of a constant war against American dominance and American incursions. The Russian trolling and hacking during the 2016 U.S. presidential election was part of this policy.

McCain never appeared to feel a need to learn more about how Russia worked. In 2013, the pro-Kremlin site Pravda.ru (no relation to the official paper of the Soviet Communist Party) published McCain’s attempt to talk directly to Russians about the the Putin regime’s failings.

“I am pro-Russian, more pro-Russian than the regime that misrules you today,” he wrote, adding, “a Russian citizen could not publish a testament like the one I just offered.” The uninformed choice of the venue and McCain’s obvious conviction that Russians couldn’t criticize Putin in print – incorrect even today – contributed to the caricature image of “America’s chief Russophobe.”

Kremlin propagandists will miss McCain. Other U.S. politicians who have ridden the post-2016 anti-Russia wave aren’t as focused on fighting Russian expansionism and helping Putin’s enemies throughout eastern Europe. Nor are they as emotionally involved or gaffe-prone. Without McCain, it’s harder to paint the U.S. as intrinsically hostile to Russia.

I will miss him for a different reason. Even if he was often wrong about details, he was right about important fundamentals. Imperialism and authoritarianism need to be challenged even when political realism counsels against it. Plain speaking often causes eye rolls among experts, but it’s still a virtue in a politician and McCain never pretended to be a wonk. Russians deserve a better government than the one they have today, and if McCain’s belief in their ability eventually to establish one was naive, then so is mine.

I have no illusions about more nuanced approaches to Russia winning out in the U.S. now that McCain is gone. He at least had the virtue of sincere conviction, which even Putin respected (“I like him for his patriotism and his consistency in defending his country’s interests,” Putin said last year). But no living politician can match it or back it up with a personal history like McCain’s. The Putin regime liked McCain as an enemy – but Russia, in the final analysis, needed the regime to have an enemy with McCain’s moral clarity, and the ex-Communist countries needed the hope and inspiration that this clarity provided.

Leonid Bershidsky is a Bloomberg Opinion columnist covering European politics and business. He was the founding editor of the Russian business daily Vedomosti and founded the opinion website Slon.ru. The views and opinions expressed in opinion pieces do not necessarily reflect the position of The Moscow Times.

A Message from The Moscow Times:

Dear readers,

We are facing unprecedented challenges. Russia's Prosecutor General's Office has designated The Moscow Times as an "undesirable" organization, criminalizing our work and putting our staff at risk of prosecution. This follows our earlier unjust labeling as a "foreign agent."

These actions are direct attempts to silence independent journalism in Russia. The authorities claim our work "discredits the decisions of the Russian leadership." We see things differently: we strive to provide accurate, unbiased reporting on Russia.

We, the journalists of The Moscow Times, refuse to be silenced. But to continue our work, we need your help.

Your support, no matter how small, makes a world of difference. If you can, please support us monthly starting from just $2. It's quick to set up, and every contribution makes a significant impact.

By supporting The Moscow Times, you're defending open, independent journalism in the face of repression. Thank you for standing with us.

Remind me later.