Ryazan, a provincial town 200 miles south east of Moscow, is probably best known as the home of the Russian Air Force’s largest base, Dyagilevo.

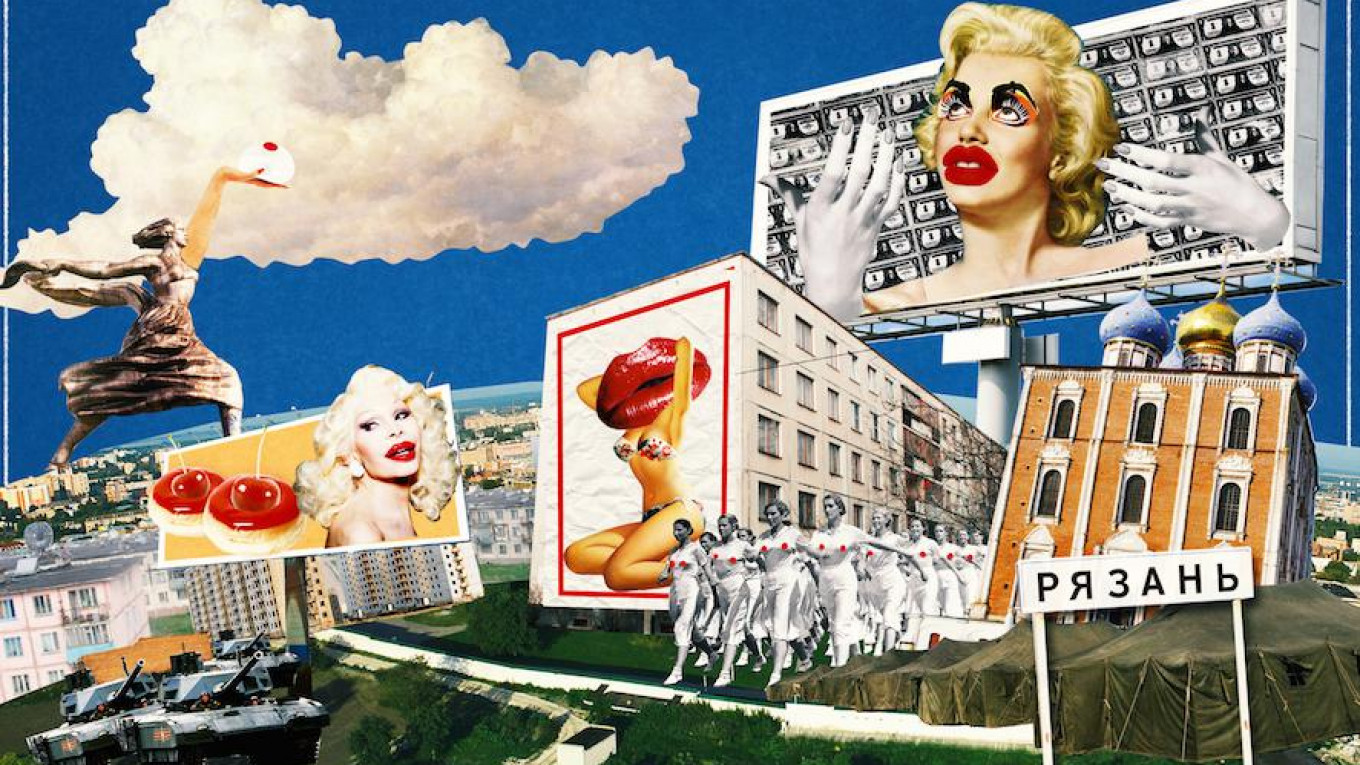

The highway from Moscow is lined with military artefacts of all sorts—from vintage Soviet bomber jets to posters of Russian soldiers and paratroopers. But past the army barracks and military memorabilia, the city turns into a series of advertisements for a very different industry: plastic surgery.

Former governor and local businessman Sergei Kuznetsov began investing in Ryazan’s beauty industry in the early 2000s. He began by setting up his own private cosmetic surgery clinics and luring Russia’s best plastic surgeons to his native city. Since then the sector has enjoyed a mini-boom.

For a town of less than half a million people, there are surprising 6 plastic surgery clinics in Ryazan—and this number does not include the doctors practicing plastic surgery in local state hospitals.

The industry has proven so lucrative that women from Moscow have been traveling to Ryazan to undergo cheaper, but top quality, boob and nose jobs.

Two sizes bigger

The most successful plastic surgery clinic in town is Da Vinci. It is housed on the ground floor of a Soviet-era Khrushchevka apartment building, just off Ryazan’s main square.

“Plastic surgery is no longer the luxury it once was,” says the young, fake blonde and heavily made-up receptionist, who is sitting behind a purple desk. But the growing popularity of surgery means it is not always easy to get a slot at Da Vinci.

“We often have a waiting list of at least two months,” the receptionist says.

Alexandra (not her real name) has driven from her small town in the Moscow region to undergo a breast enlargement in Ryazan. It’s not her first operation. The 37-year-old has already had work on her nose and cheeks. She has also had her breasts lifted, but never with implants.

“People ask me if I do it for men,” says the single mother of two. “What a stupid question! I just like being in control of my body.” She has never been happy with the size of her breasts, she says, and would like them to be “at least two cup sizes” bigger.

Alexandra underwent her first operations in Moscow, but a friend recommended her to try a Ryazan clinic. “It’s almost a third of the price I paid in Moscow, and the surgeons here have a really good reputation,” she tells The Moscow Times.

Since Russia recognized plastic surgery as a medical practice in 2009, cosmetic operations have grown in popularity among Russian women, who are famously beauty conscious. While plastic surgery was once only available to Russia’s urban elite, it is now widely available throughout the country and affordable to a much greater portion of the population.

The practice has become so popular in Russia’s provinces that pro-Kremlin TV channel NTV recently launched reality show “Beauty a la Russe,” in which the presenter travels through Russia meeting women and their surgeons. A 2016 survey conducted by Moscow’s main plastic surgery institute found that one in thirty Russian women have undergone some kind of plastic surgery.

But the practice is not just confined to Russian women. After all, Russia’s most famous plastic surgery patient may well be in the Kremlin: the changing face of Vladimir Putin over his eighteen years in power suggests the president has possibly undergone more than one plastic surgery operation.

Plastic surgeons The Moscow Times spoke to for this article declined to comment on Putin’s face. Just like the president’s family, his rumoured botox injections are not a topic for public discussion.

“He looks good,” Alexandra, the Da Vinci patient, says. “If only all Russian men in their 60s looked like him.”

Beauty for the tsars

It is no coincidence that Ryazan has turned into a mini beauty capital. The city is home to the world’s first make-up shop, which paved the way to a multi-million empire that took over Hollywood in the 1920s: Max Factor.

The Max Factor make-up giant was founded by Polish Jew Maksymilian Faktorowicz. Born in Lodz, then one of the Russian Empire’s largest industrial hubs, Faktorowicz went on to become chief cosmetic for the Russian imperial family in St. Petersburg.

In 1897, he founded a make-up store and salon on Ryazan’s main "Postal Street’ (then known as “Happy Street” and now a pedestrianized boulevard). Faktorowicz fled Russia following anti semitic pogroms which spread across the Russian Empire, including in Ryazan, in 1904.

Faktorowicz supposedly used his make-up to make himself look sick, which allowed him to get to what is now Karlovy Vary in the Czech Republic. From there, he boarded a ship for the States, where American authorities registered him as Max Factor at Ellis Island.

“This is not an art,” Faktorowicz told a Hollywood reporter in Los Angeles in 1924.

“It is a business.”

All that is left of that business in Ryazan is a dilapidated low-rise, Tsarist-era, red-brick building. But Faktorowicz’s legacy lives on.

Things go wrong

Perhaps this unique history is part of the reason why plastic surgeons have found such a home in Ryazan. The more immediately tangible reason, however, is the town’s close proximity to the Russian capital, with its big bucks, bling and body culture.

“We are close enough to Moscow for our clients to get to us easily,” says Da Vinci’s leading surgeon Viktor Bezukov.

On average, Bezukov performs a dozen operations a week. The most common procedures are face lifts, which cost 26,000 rubles ($450) on average. The surgeon has built an enviable reputation in town, and judging by complementary posts left by women on local beauty forums, he is easily the most popular surgeon in the region.

“Like all beauticians, I want women to feel comfortable in their own skin,” says Bezukov. “It’s my profession to ensure this.”

The surgeon says that most patients worry about safety, but that standards are improving in the industry.

Sometimes things can go wrong, especially when operations are conducted by unqualified surgeons. Last year, Ryazan made national headlines when a 32-year-old woman died on the operating table during a nose enhancement procedure. She had suffered heart failure whilst unconscious and under general anaesthetic.

“As a surgeon, that incident horrified me,” says Berzukov.

Following the incident, local authorities and federal security officers (FSB) searched Ryazan’s plastic surgery clinics.

Practitioners stress the need for water tight regulation. “Getting the appropriate training and operating within the law is essential,” surgeon Vyacheslav Ivanov told The Moscow Times.

Silicone for the people

The incident did not, it seems, put off clients from flocking to Ryazan’s clinics.

Both Berzukov and Ivanov say—on the contrary—their clientele is growing, and it includes an ever wider cross-section of Russian society.

When the former governor set up Ryazan’s first clinics in the early 2000s, the regulars were primarily the wives of local officials; today’s patients are more diverse.

“We have girls of all ages over 18 and of all sizes,” says Ivanov. “It’s becoming more like going to the dentist: Plastic surgery is, and should be, for the people.”

A Message from The Moscow Times:

Dear readers,

We are facing unprecedented challenges. Russia's Prosecutor General's Office has designated The Moscow Times as an "undesirable" organization, criminalizing our work and putting our staff at risk of prosecution. This follows our earlier unjust labeling as a "foreign agent."

These actions are direct attempts to silence independent journalism in Russia. The authorities claim our work "discredits the decisions of the Russian leadership." We see things differently: we strive to provide accurate, unbiased reporting on Russia.

We, the journalists of The Moscow Times, refuse to be silenced. But to continue our work, we need your help.

Your support, no matter how small, makes a world of difference. If you can, please support us monthly starting from just $2. It's quick to set up, and every contribution makes a significant impact.

By supporting The Moscow Times, you're defending open, independent journalism in the face of repression. Thank you for standing with us.

Remind me later.