It’s "strange bedfellows week" on Moscow television, as the small screen offers its audience great literature (live!), regrettable war criminals (dead!) and a longtime Russian rock star whose early work during perestroika will impress you – as it did the New York Times. Here’s the where and when:

In Russia a poet is more than a poet, as the late Yevgeny Yevtushenko famously observed, and on MONDAY and TUESDAY viewers get an encouraging object lesson in how true that still is: the Kultura channel takes reader-viewers to the symbolic heart of Russia to report live, four times each day, from the “Red Square Book Festival.”

The entire expanse between the History Museum and St. Basil’s will be chock-a-block with books, around which will be staged “meetings with authors, book presentations, master classes and discussions on writing, theatrical presentations and concerts, literary quizzes and interactive games, and a good deal more” – all in honor of June 6, the birthday of the original more-than-a-poet, Alexander Pushkin (aka “наше всё”/“our everything”), which is also celebrated as the Day of the Russian Language. Tune in Kultura’s “special reports” to follow the literary action in all its enlightening, amusing and diverting forms – and yes, home in on a tome or two for your summer reading list.

Red Square Book Festival: Live Coverage / Книжный фестиваль "Красная площадь" в прямом эфире. Kultura, Monday and Tuesday at 12:30 p.m., 3:10 p.m., 6:10 p.m. and 7:45 p.m.

It’s a good thing indeed that TV can spend several days reminding us that reading is fundamental – and no less important that the small screen dedicates much of the rest of this week to reminding viewers, directly and indirectly, of another useful maxim: that those who ignore history are condemned to repeat it. The Zvezda channel leads by offering the Oleg Shtrom documentary "Nuremburg" (2016) in four parts MONDAY through THURSDAY evenings: “The Trial That Might Not Have Been”; “The Trial Through the Eyes of Journalists”: “The Banality of Evil”: and “Blood Money: Judging the Manufacturers.”

For anyone who doubts the continued importance in Russia of recalling the entirety of World War II, from its onset in 1939 to the postwar adjudication by the victors at Nuremburg, the troubling trends in local historiography surely demonstrate why documentaries like this one matter: Less than a year ago Russia’s Supreme Court upheld the conviction of a blogger in Perm for reposting a factual statement about the beginning of the war that the court somehow deemed a “public denial of the Nuremberg trials.” This was a decision widely described as absurd on the face of it, but one that doubtless succeeded in sending a chilling message to Russian social media users as to who is in charge of history here.

If the serialized Shtrom feature is not on a level with Christian Delage’s 2006 classic “Nuremberg: The Nazis Facing Their Crimes” (“Нюрнберг. Нацисты перед лицом своих преступлений) – which Kultura, commendably, has aired several times in recent years – it is in any case an important and timely contribution to the literature on the subject.

Nuremburg / Нюрнберг. Zvezda, Monday through Thursday at 6:40 p.m.

Late TUESDAY night the Who’s Who (Кто есть кто) channel puts the question another way: if the Zvyagintsev documentary explains why one Nuremburg tribunal was necessary, Igor Kholodkov’s “The Nuremburg That Wasn’t” (2009) explains why another was not – specifically, why the mass crimes against humanity committed in Russia during the Soviet period were not brought before some august body to be publicly judged and forcefully condemned once and forever.

And this might have happened, it seems. As the channel’s program summary puts it, “There was a time when ‘a Russian Nuremberg’ could have taken place, initiated by [Gulag veteran] Olga Shatunovskaya and a group of ex-prisoners who had considerable influence on [post-Stalin premier Nikita] Khrushchev. Some 64 volumes of terrifying documentation incriminating Stalin and his executioners were collected. But these executioners…were able to persuade Khrushchev to postpone publication of the materials for two years – which proved time enough to force his resignation and destroy almost all the documents.”

The documentary’s text is by Irina Vasileva, author of the moving 2005 documentary “Beslan: City of Angels” (“Беслан – город ангелов”); much of the background and on-point commentary comes from interviews with Grigory Pomerantz, the philosopher/critic (and Gulag survivor) who became an important human rights leader here in the 1960s and 70s and wrote on the Shatunovskaya initiative. Tune in for a saddening but enlightening account of history-that-might-have-been – which you are not likely to see recounted any time soon on the central state channels.

The Nuremburg That Wasn’t / Hюрнберг, которого не было. Кто есть кто, Wednesday at 00:45 a.m.

Late WEDNESDAY night the Viasat History channel likewise draws on the story of the Third Reich – this time from its beginning rather than its end – with the German documentary “Hindenburg: The Man Who Made Hitler Chancellor” (2013). This well-received Christoph Weinert 90-minute feature makes a number of telling points that local viewers would do well to digest and bear in mind – especially when looking back over events of the transitional period of 1999-2000 in Moscow.

As the film’s capsule summary puts it, “Prior to Hitler's appearance, Paul von Hindenburg was the most charismatic political leader in Germany. He was the most successful German general of the First World War, thanks to which he became a hero in the eyes of the people. After the war, he was twice elected president of the Reich – the only person in German history to that time elected head of state in popular elections. Hindenburg held the office for the rest of his life, but was challenged by the political upstart Adolf Hitler. Hindenburg despised him, but only a few years [after they met], he would bring Hitler to power. Why?”

Why indeed. Viewers know all too well, of course, what this unfortunate turn of events led to – for Germany, for Russia and for most of the world. A good reason to watch, beyond the edifying historical narrative, is to ponder whether ways might have been found to deprive Hitler of the power handed him by Hindenburg years before humanity had to pay the terrible price it finally did.

Hindenburg: The Man Who Made Hitler Chancellor / Гинденбург и Гитлер. Viasat History, Thursday at 00:40 a.m.

On FRIDAY Kultura revisits its Portrait of a Generation rubric for Valery Ogorodnikov’s “The Burglar” (1987), a perestroika-era youth film which says a great deal about the kids who weren’t all right 30 years ago. Or rather sings a lot about them, as something like half the movie is given over to Leningrad rock of the day performed by the likes of Alisa, Auktyon, AVIA, Buratino, Kofe and Prisutstvie.

“The Burglar” does have a functional plot: Retreating from a mom’s-gone-dad’s-an-alcoholic broken family, two teenage brothers in Leningrad navigate their way through life in a society at once coming apart, as Communism loses its grip, and coming together, as things foreign – particularly Western music – fill the gap. Younger brother Senka will do whatever he can to help older brother Kostya, who has adopted rebellious punk rock as a way of life and landed in a tough spot; Senka’s commitment leads to a denouement you’ll see coming a mile away – but one which unarguably fits the times.

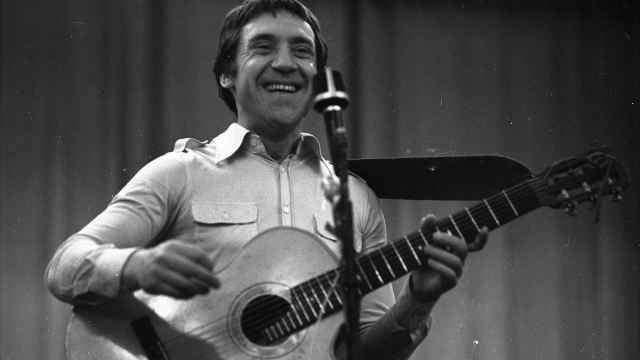

While “The Burglar” won a modest clutch of foreign and domestic awards, it does not rival the depth and polish of the best youth-angst films of its era – Karen Shaknazarov’s “Courier ” (1986), Sergei Solovyov’s “Assa” (1987) and Valery Rybarev’s “My Name Is Arlekino” (1988), for our money. That said, the movie’s considerable virtues are quite real: “The Burglar” offers an engaging sociology of perestroika at the ground level, and it provides a fine platform for the musical and dramatic talents of Alisa frontman Konstantin Kinchyov (as Kostya).

Kinchyov (b. 1958) claims to have taken the role merely as a way to get around the Soviet anti-unemployment (“тунеядство”) law – yet his acting won praise from Janet Maslin of the New York Times (“uncomplicatedly sincere”) and brought him the Sofia International Film Festival’s Actor of the Year award. Tune him in for a look and a listen that will remind you why perestroika had to happen…and something rather like it must needs happen again.

The Burglar / Взломщик. Kultura, Friday at 11:50 p.m.

Mark H. Teeter is the editor of Moscow TV Tonite on Facebook.

A Message from The Moscow Times:

Dear readers,

We are facing unprecedented challenges. Russia's Prosecutor General's Office has designated The Moscow Times as an "undesirable" organization, criminalizing our work and putting our staff at risk of prosecution. This follows our earlier unjust labeling as a "foreign agent."

These actions are direct attempts to silence independent journalism in Russia. The authorities claim our work "discredits the decisions of the Russian leadership." We see things differently: we strive to provide accurate, unbiased reporting on Russia.

We, the journalists of The Moscow Times, refuse to be silenced. But to continue our work, we need your help.

Your support, no matter how small, makes a world of difference. If you can, please support us monthly starting from just $2. It's quick to set up, and every contribution makes a significant impact.

By supporting The Moscow Times, you're defending open, independent journalism in the face of repression. Thank you for standing with us.

Remind me later.