The dust is now settling after the landslide victory this Sunday by Vladimir Putin and United Russia — a showing so good that the party will now enjoy a constitutional super-majority in the new parliament. The opposition didn’t win a single seat. The Kremlin is celebrating this week, but what is next for a regime that has become increasingly subjugated over the past three years to Vladimir Putin’s personal rule?

“United Russia got a good result,” Putin declared the day after the election. “How is that possible, given the economic difficulties we’ve been facing and the drop in people’s real incomes? It's because at times of risk, you can count on people to choose stability and trust the government.”

It seems Putin is correct, at least to a certain extent. “People vote rationally,” says Natalya Zubarevich of the Independent Institute of Social Policy. “And when the economy is weakening gradually, paternalistic instinct wins: people vote for those they think can help — for the authorities.”

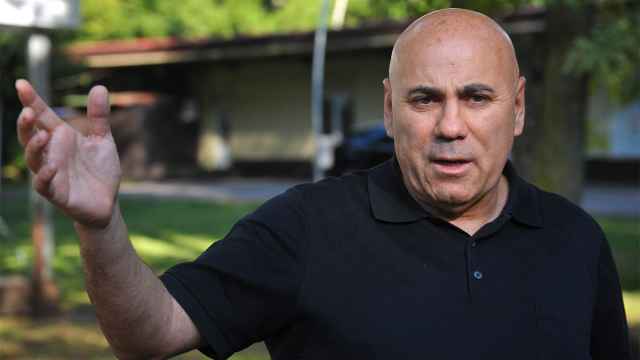

Still, turnout in this election was the lowest it’s been in recent history. People in the big cities, home to Russia’s more progressive citizens, largely abstained from voting, handing Putin his victory on Sunday. “The new parliament consists of apparatchiks [political establishment members], elected in the villages of Povolzhye and the North Caucasus,” says Gleb Pavlovsky, a former Kremlin advisor.

United Russia won 54 percent of the general vote, but translated into real numbers (25 million votes), the party’s victory is less impressive: not even a fourth of the national electorate gave its support.

From this perspective, this is the weakest parliament since 2007, says Konstantin Gaaze, a political journalist. Low turnout means that this Duma is “politically unwanted,” and will need “help from above,” Gaaze says.

This Duma has the unhappy task of tackling a declining economy. Money is so short that the government is taking the unprecedented step of distributing one-time payments of 5,000 rubles ($77) to tide pensioners over for a whole year, instead of indexing social benefits to inflation in 2017, as economic analyst Boris Grozovsky wrote in an Op-Ed for The Moscow Times.

Under these circumstances, pressure from the Duma’s new members will present another challenge for the Kremlin. “The budget of 2017 is already allocated, but it doesn’t take into account the 200 new deputies elected in single-constituency races. They will want to take part [in budget negotiations], too,” Gaaze explains.

The Duma’s new directly elected lawmakers will be more dependent on the local elites from their districts. “In a way, these deputies will look more like American congressmen. The ones elected directly will lobby for their local interests more effectively,” says Alexei Makarkin, a political analyst.

The new Duma will be at the bidding of the Kremlin like never before, Makarkin says, with United Russia’s constitutional super-majority that allows it to dominate and pass any legislation it wishes. No obstacles remain.

There might be relatively little left for the new Duma to do, however. Yevgeny Minchenko, a political analyst, says the parliament’s new members were elected without a mandate and without a plan.

“This parliament — this whole political system — doesn’t have a real agenda,” agrees Pavlovsky. The Kremlin sees the Duma as the last brick in the construction of Russia’s new political system, which transformed dramatically in the last four years. The so-called “managed democracy” of the 2000s has given way to direct authoritarian rule. Sociologically, Vladimir Putin’s image has morphed into the portrait of a warlord.

“The new Duma has to become the parliament of development. There is a mandate for this, as well as expectations,” Alexei Kudrin, the deputy head of the president’s economic council and Russia’s former finance minister, tweeted the day after the election. The responses online virtually exhausted Twitter’s supply of laughs. “Alexei, are you serious or are you just joking?” Andrei Nechayev, a former economic development minister, replied.

Analysts don’t expect any shifts in Russia’s economic policy after the parliamentary election. “The shortage of funds will probably force the authorities to raise the retirement age and income taxes, but naturally only after 2018,” following the next presidential election, Boris Grozovsky writes.

The long interval between the two elections is a trap, argues Nikolai Petrov. If Putin waits another 18 months before implementing essential but painful economic reforms, the government’s financial reserves will be exhausted, he says.

So, what is Vladimir Putin’s plan for 2018? He doesn’t necessarily need to wait that long. “He still might decide on a successor, but psychologically, for both Putin and the entire political elite, it is much more comfortable for him to stay,” Yevgeny Minchenko says. “Here he has two options: he runs in 2018, or the Kremlin makes some technical changes, with the help of the Duma (which won’t get in its way), and organizes an early election.”

But another national vote so soon after this latest contest might be asking too much of an electorate that has just made its political apathy all too clear. How might Putin plan to mobilize his supporters? “This is the major puzzle,” says Konstantin Gaaze. “People are simply tired.”

According to Pavlovsky, the Kremlin’s real challenges are still ahead, in 2018. The problems of that race, he says, “are probably unsolvable under the system that has been built.” And all the loyal men and women just elected to serve in Putin’s new parliament will be of little help to him when he has to turn to voters to gain a fourth term.

A Message from The Moscow Times:

Dear readers,

We are facing unprecedented challenges. Russia's Prosecutor General's Office has designated The Moscow Times as an "undesirable" organization, criminalizing our work and putting our staff at risk of prosecution. This follows our earlier unjust labeling as a "foreign agent."

These actions are direct attempts to silence independent journalism in Russia. The authorities claim our work "discredits the decisions of the Russian leadership." We see things differently: we strive to provide accurate, unbiased reporting on Russia.

We, the journalists of The Moscow Times, refuse to be silenced. But to continue our work, we need your help.

Your support, no matter how small, makes a world of difference. If you can, please support us monthly starting from just $2. It's quick to set up, and every contribution makes a significant impact.

By supporting The Moscow Times, you're defending open, independent journalism in the face of repression. Thank you for standing with us.

Remind me later.