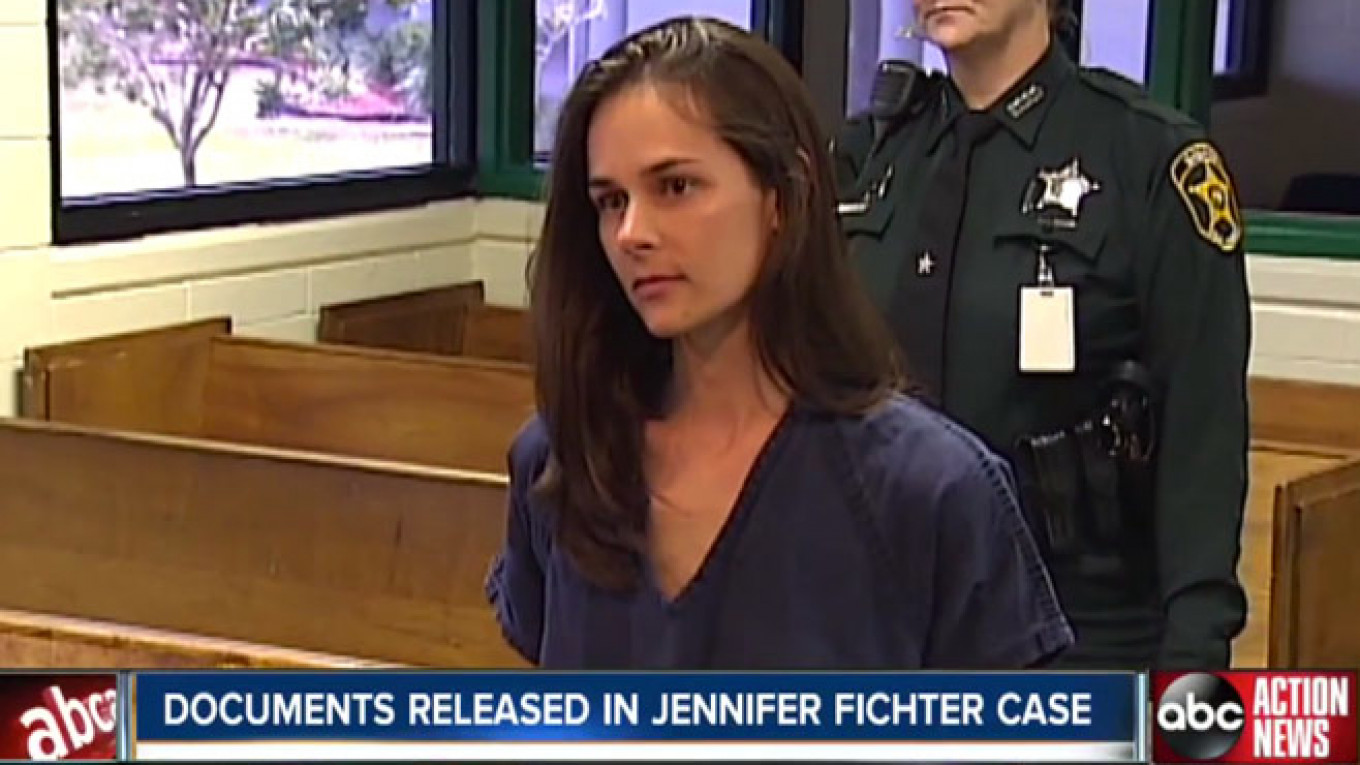

The news that the former U.S. schoolteacher Jennifer Fichter was sentenced to 22 years in prison for multiple counts of sex with minors caused an uproar on Russian social media. The story was covered by major national news portals, attracting thousands of mainly indignant comments.

One angry Russian Internet user started an online petition, calling for Fichter's immediate release. The petition, signed by tens of thousands in a few hours, called for stopping "legal despotism" in the United States and annulling the sentence. The Russian version of the popular men's magazine Maxim summed up the prevailing sentiment: "She is too pretty to spend 22 years behind bars!"

This spontaneous outpouring of sympathy for a woman ostensibly sentenced for pedophilia is all the more surprising, given the generally hostile views of what the Russians perceive to be degraded ethical standards of the decadent West.

The Russian media commentary on the recent decision by the U.S. Supreme Court to legalize gay marriage was on the whole toxically homophobic; this victory for gay rights was seen in Russia as a sure sign of moral decay. But if the United States is so immoral and perverse, then why would a decision to punish a sex offender suddenly meet with such vocal Russian resistance?

The reason is a very peculiar distinction that Russians make between the notions of "legality" and "justice." In short, not everything that is legal is just, and not everything that is just is legal. This understanding is rooted in Russia's brutal past.

For instance, political repressions in the Soviet Union were carried out within the framework of the law. Hundreds of thousands of people who were unjustly sentenced to death or to slave labor in the gulag were persecuted in accordance with specific articles of the Criminal Code.

From more recent memory, the reason why the vast majority of Russians supported the lengthy imprisonment of the former oligarch and Putin critic Mikhail Khodorkovsky was not because it was in accordance with the letter of the law but because it was seen as just. Khodorkovsky suffered for the perceived collective injustice perpetrated by the greedy oligarchs in the 1990s. Privatization of Soviet-era assets or simply rapid accumulation of wealth may have appeared legal on paper but was seen as manifestly unjust by the majority of Russian people.

A very recent example of this dichotomy between "legality" and "justice" was the Russian takeover of Crimea. Seen in the West as an illegal seizure of a neighboring state's territory, Putin's annexation of Crimea enjoyed wide support across all social strata in Russia precisely because of the public perception that it restored "historical justice."

The idea here is that Crimea was unjustly given away; therefore, it has to be returned — not because this is a legal proposition but because doing so accords with a vague sense of what is right.

Putin has also made repeated appeals to "justice" in the context of his efforts to reshape the international system. The idea of a "just world order" is invariably brought up in Moscow's foreign policy statements, while the notion of "legality" is rarely broached. Putin is true to the Russian saying: The law is like a rudder, it goes where you turn it. Justice, by contrast, is something absolute: it is sensed, not written. It is handed down from God.

The Russian uproar over Jennifer Fichter's case is yet another example of the tendency to separate legality from justice. The view in Russia is that although the woman did wrong, her victims partook of the pleasures, and so of the responsibility. The distinction between adults and children is lost on most Russian commentators. After all, in their view, the law can be ambiguous but justice never is.

Sergey Radchenko is global fellow at the Woodrow Wilson International Center for Scholars in Washington, and reader in international politics at Aberystwyth University in Wales.

A Message from The Moscow Times:

Dear readers,

We are facing unprecedented challenges. Russia's Prosecutor General's Office has designated The Moscow Times as an "undesirable" organization, criminalizing our work and putting our staff at risk of prosecution. This follows our earlier unjust labeling as a "foreign agent."

These actions are direct attempts to silence independent journalism in Russia. The authorities claim our work "discredits the decisions of the Russian leadership." We see things differently: we strive to provide accurate, unbiased reporting on Russia.

We, the journalists of The Moscow Times, refuse to be silenced. But to continue our work, we need your help.

Your support, no matter how small, makes a world of difference. If you can, please support us monthly starting from just $2. It's quick to set up, and every contribution makes a significant impact.

By supporting The Moscow Times, you're defending open, independent journalism in the face of repression. Thank you for standing with us.

Remind me later.