A corpse on a bloodstained bridge, with the Kremlin's red stars glowing behind: the perfect symbolic backdrop, Russian media say, for the West to step up a campaign to vilify President Vladimir Putin.

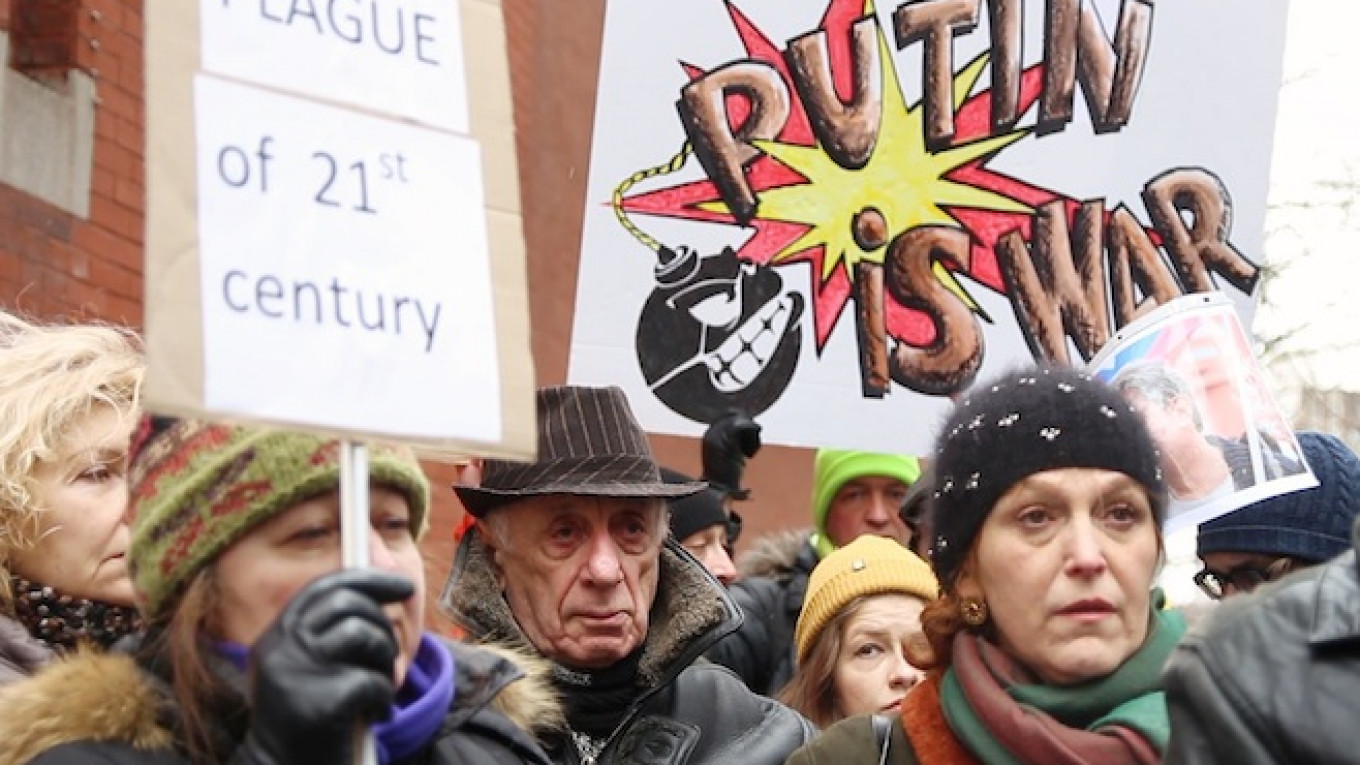

Faced with a wave of revulsion around the world at the assassination of leading opposition figure Boris Nemtsov, the loyal media establishment is on the counter-attack, preparing Russians for a malicious propaganda campaign by a hostile West.

"And they say that's how the 'bloody regime' kills its competitors. The world is outraged and indignant. And then — sanctions, credit downgrades and the further demonization of Russia and its leader," Dmitry Kiselyov, a television anchor reputed to be one of Putin's favorite journalists, told his prime-time audience on Sunday evening.

"At a time when there is grief, to engage in polemics is disgusting."

With the gunning-down of Nemtsov in central Moscow late Friday, Russia enters a new phase of the 'us or them' tug-of-war that has played out in the media, increasingly pliant to Putin, since Ukrainians took to the streets and overthrew their Moscow-leaning president just over a year ago.

Russia accused the West of backing 'a coup d'etat' in Ukraine. Now those who support the West or Ukraine are called traitors or a 'fifth column,' a term Putin used a year ago to suggest the presence of internal enemies ready to help stir up discontent.

It was a term familiar to Nemtsov who, along with many opposition figures, had criticized Putin for annexing Ukraine's Crimea peninsula, supporting separatists in east Ukraine and causing the West to impose sanctions on Russia.

While the murder is so far unsolved, Putin's critics say the 'fifth column' rhetoric has helped to create a climate in which pro-Kremlin hardliners could have felt they were performing a patriotic duty in disposing of a man like Nemtsov.

'Boris Will Be Missed'

In his Sunday night show, Kiselyov moved away from Putin's initial characterization of the murder as a 'provocation' meant to undermine the Kremlin chief.

Putin is an elected leader whose popularity ratings have hit 86 percent, Kiselyov pointed out. Nemtsov, he implied, was an opposition figure of little significance, not to be compared with the president.

Instead, he claimed Nemtsov as Russia's own, calling him by his first name and describing him as a "muzhik," a typical Russian bloke, and a charmer.

"He was seen as a handsome, charismatic, open and energetic man. An artistic orator with a biting tongue ... And of course Boris will be missed like spice, which in small doses can give a rich taste," he said.

Russian officials, most of whom have followed Putin by blaming the country's woes largely on the West, took a similar line to Kiselyov on Monday.

Foreign Minister Sergei Lavrov told the United Nations Human Rights Council it was "sacrilege to use such tragedies ... to try to substitute investigators and law enforcement organs by pushing politicized, ungrounded and provocative interpretations".

Rift Widens

Russia still has some independent media critical of the government and, at times, Putin. The president is frequently satirized on the Internet; a few newspapers such as Novaya Gazeta, part-owned by former Soviet leader Mikhail Gorbachev, are fiercely critical of him.

But the vast majority of Russians get their news from television, and all the main channels are either in the hands of the state or of business leaders loyal to the Kremlin.

Reactions to the murder underscored a rift in society between a small liberal middle class, which feels marginalized and fearful of expressing its views, and a pro-Putin majority that opponents see as increasingly strident and aggressive.

The authorities have come up with several possible motives and lines of investigation, from jealousy over Nemtsov's girlfriend, model Anna Duritskaya, to his support of French satirical weekly Charlie Hebdo over its cartoons of the Prophet Mohammad.

They are also muddying the waters, reminding people Nemtsov had visited and supported Ukraine, had a much younger girlfriend, and was once a deputy prime minister who may have had rivals and enemies.

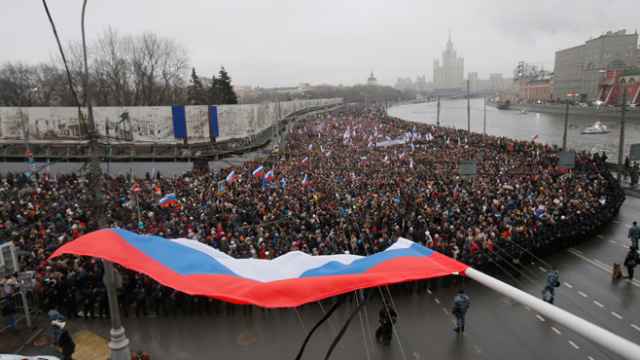

The arguments did not deter tens of thousands from marching in big cities on Sunday holding banners declaring: "I am not afraid." Many said they feared for the future of Russia.

But a Twitter feed belonging to rebels in eastern Ukraine under the name "Strelkov," in homage to a former Russian rebel commander who fought there, called Sunday's march "a gay parade for Ukraine supporters and liberals." Gay is a term that is used as an insult by some conservatives.

Opposition leaders have failed so far to unite the critics of Putin's leadership, hamstrung by his popular appeal to patriotism. Nor have they been able to overcome their own rivalries and differences.

But Nemtsov's murder may have broken a psychological barrier, wrote Vedomosti, a business daily that is critical of the government and whose future is in doubt.

"It has happened at a moment when society is in the middle of a cold civil war," said the newspaper, adding that such killings often prompt leaders to pursue tougher policies.

A tightening of the screws, it said, "would mean the almost complete political and economic closure of the country, the severe repression of those who disagree, and put the kibosh on the economy."

A Message from The Moscow Times:

Dear readers,

We are facing unprecedented challenges. Russia's Prosecutor General's Office has designated The Moscow Times as an "undesirable" organization, criminalizing our work and putting our staff at risk of prosecution. This follows our earlier unjust labeling as a "foreign agent."

These actions are direct attempts to silence independent journalism in Russia. The authorities claim our work "discredits the decisions of the Russian leadership." We see things differently: we strive to provide accurate, unbiased reporting on Russia.

We, the journalists of The Moscow Times, refuse to be silenced. But to continue our work, we need your help.

Your support, no matter how small, makes a world of difference. If you can, please support us monthly starting from just $2. It's quick to set up, and every contribution makes a significant impact.

By supporting The Moscow Times, you're defending open, independent journalism in the face of repression. Thank you for standing with us.

Remind me later.