Foreigners familiar with Chekhov's plays might conclude that Russians are naturally prone to melancholy. However, I believe Russians are actually more optimistic than Westerners.

For example, Westerners love to quote Murphy's law stating that "anything that can go wrong will go wrong." And don't try convincing me that Murphy's law is just a joke. As the saying goes, "every joke contains an element of truth."

Russians, meanwhile, prefer to use the word avos — a rough equivalent to the English word "maybe" that carries an element of existential hope.

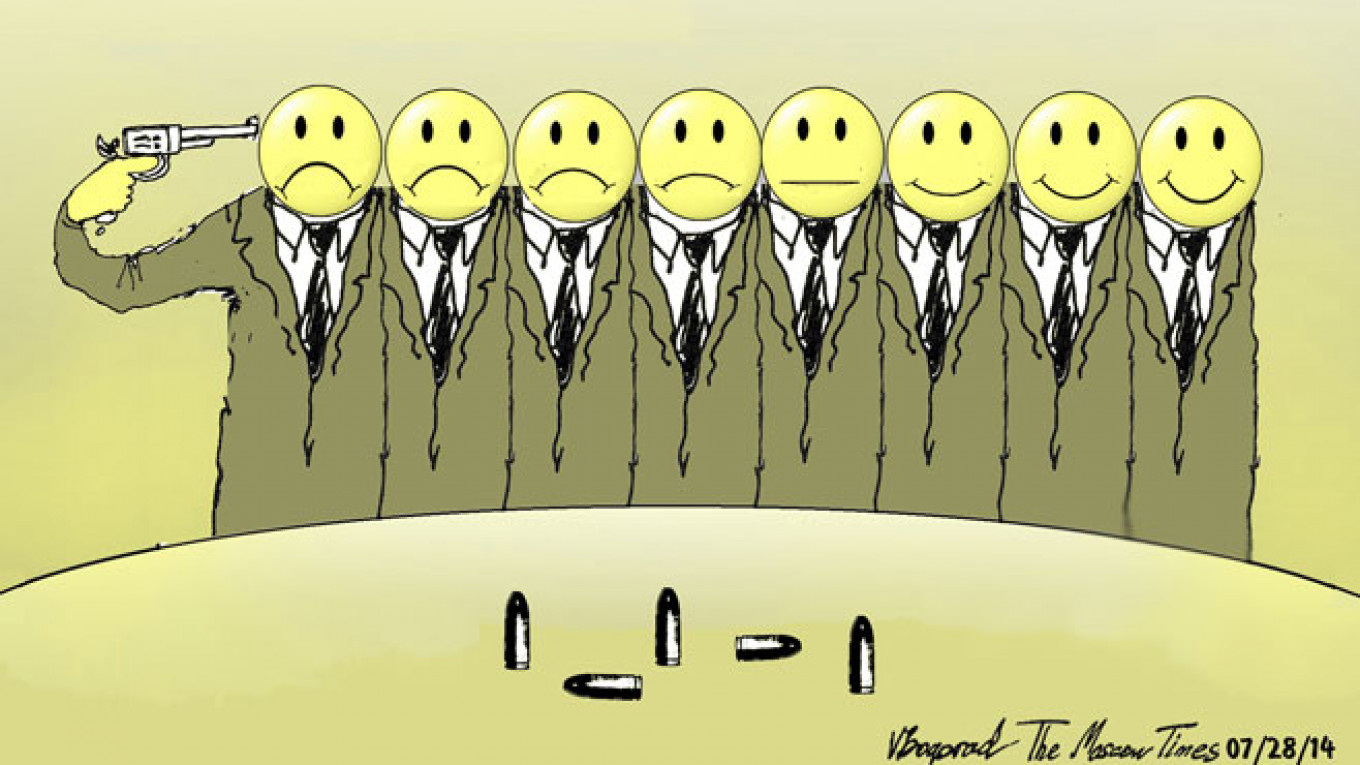

It is impossible to give an exact English rendering of avos, but it is similar to the idea behind Russian roulette — namely, that you might lose everything, but that odds are you will make it out alive.

In life, somehow, something or someone will come to your aid. If not, pure chance, a miracle or God himself might save you. There is always hope, right up until the very last moment. Russian army officers would never play Russian roulette if they believed in Murphy's law because then they would consider the game suicide — plain and simple. But they see it differently and find it deadly fun.

No one, not even the greatest Russian minds, has managed to determine whether the Russian avos is ultimately more positive or negative. According to famous Russian critic Vissarion Belinsky, "avos is a peculiarly Russian ailment." But Moscow State University professor Nikolai Nadezhdin disagreed. "No European language contains anything like our poetic and heroic avos," he proudly declared.

Englishman Donald Wallace, a 19th-century writer and correspondent for The Times of London who lived in Russia for five years, noted that every time he came to a decrepit bridge while traveling around the country, he would ask his coach driver whether he thought they could cross the bridge safely.

Without fail, his coachman always answered: "Not to worry, sir. Avos, we will make it." After that the coachman crossed himself, cracked his whip and boldly sent the horses into full gallop. Interestingly, in his five years in Russia, Wallace never lost a coachman to accidents, despite the substandard roads and bridges he consistently encountered in the provinces.

This country's history also reminds Russians that however bad circumstances are today, things can change for the better tomorrow or the next day. In 1812, Muscovites astonished Napoleon and his invading army by burning their city to the ground. But not long thereafter, Russian forces were marching on Paris. More than a century later, Russians first gave up half the country to Hitler, but then later took Berlin. And even at the very darkest periods in both of those struggles, Russians firmly believed in ultimate victory, however irrational that might have seemed to casual observers.

When reviewing the events of the last century alone, it seems amazing that Russia did not just roll over and give up. First, recall the wars: the Russo-Japanese in 1905, two wars with the Finns, two world wars, a civil war and the war in Afghanistan — not to mention the Cold War. There have been so many wars, in fact, that I would not be surprised if I'm forgetting one. And Russia's problems don't stop with just a few wars. Throw in the three revolutions of 1905 and February and October of 1917, Leninism, Stalinism and the socialism of aging and inept leaders. Wouldn't you quit, faced with a similar fate?

But the average Russian sat it out in the trenches as the tanks rumbled past overhead, then climbed out, tossed a grenade at the enemy, dusted himself off and went on with life. And all the while, the Russian avos served as his inspiration and guide.

I mention this not because things are so bad in Russian again, or to find fault with this or that side. That is all secondary. What is important is Russians' ability to survive, no matter the circumstances. It almost seems at times that the worse the situation becomes, the more Russians thrive. I would not exclude the possibility that the current sanctions might not only fail to achieve their goal, but could actually benefit the Russian people in some way.

Of course, it is no easy matter to deal with an unpredictable individual for whom avos is a way of life and who is always ready to risk it all in a game of Russian roulette. I can empathize with those who are wary of Russia. And, of course, Russia does not necessarily like the national characteristics of its neighbors and international partners either. But in the end, like neighbors in one large apartment building, we are all stuck with each other and must find a way to live together.

Pyotr Romanov is a journalist and historian.

A Message from The Moscow Times:

Dear readers,

We are facing unprecedented challenges. Russia's Prosecutor General's Office has designated The Moscow Times as an "undesirable" organization, criminalizing our work and putting our staff at risk of prosecution. This follows our earlier unjust labeling as a "foreign agent."

These actions are direct attempts to silence independent journalism in Russia. The authorities claim our work "discredits the decisions of the Russian leadership." We see things differently: we strive to provide accurate, unbiased reporting on Russia.

We, the journalists of The Moscow Times, refuse to be silenced. But to continue our work, we need your help.

Your support, no matter how small, makes a world of difference. If you can, please support us monthly starting from just $2. It's quick to set up, and every contribution makes a significant impact.

By supporting The Moscow Times, you're defending open, independent journalism in the face of repression. Thank you for standing with us.

Remind me later.