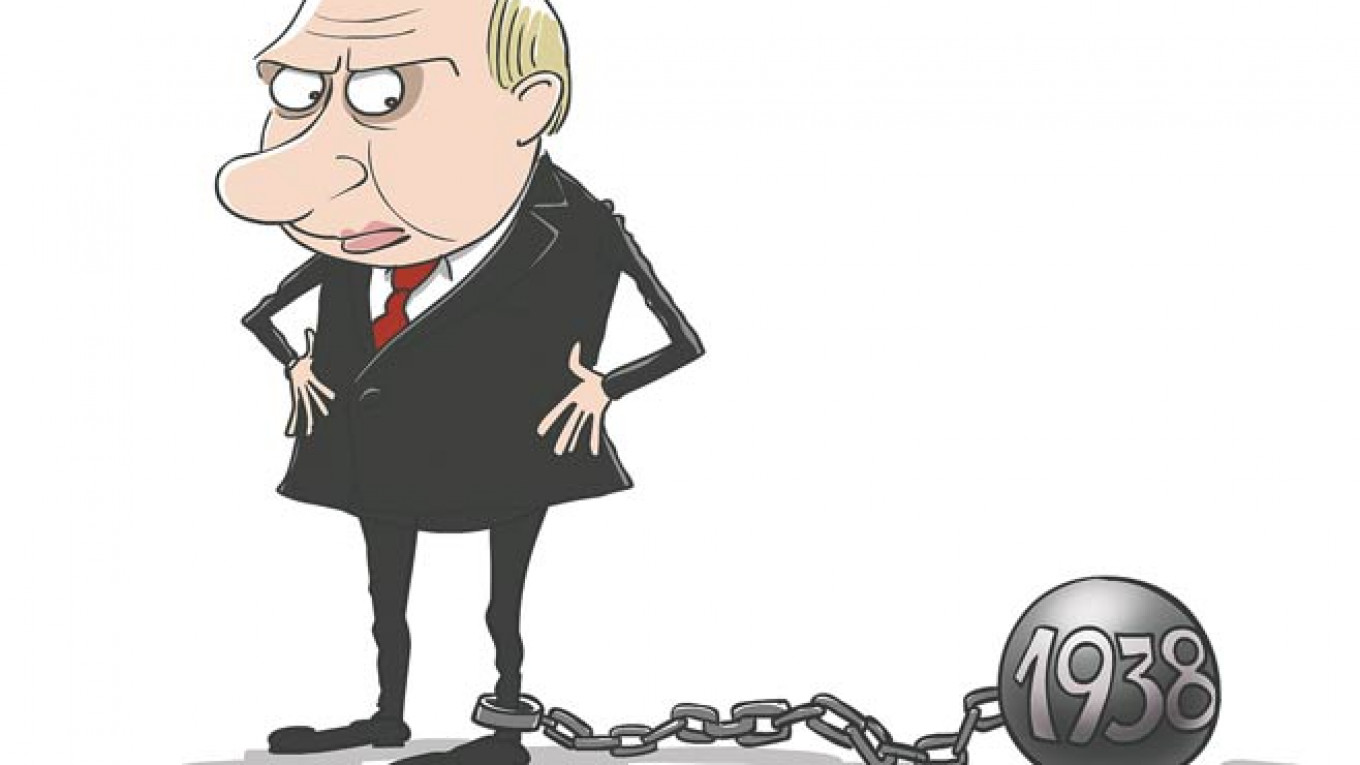

For more than a month now, the global media, including in Russia, have been discussing parallels between Russia's annexation of Crimea and Nazi Germany's annexation of Austria in 1938. Those discussions frequently also include comparisons between President Vladimir Putin and Hitler. Dozens of European magazines and newspapers publish photos and political cartoons depicting Putin in the image of the former German dictator, a practice that even many of Putin's detractors understandably find distasteful.

Are there grounds for drawing direct parallels between Putin and Hitler? No, but at the same time we should draw lessons from both Putin's domestic and foreign policies.

Although Putin's domestic policies seem tame compared to Hitler's, his foreign policy could be just as disruptive.

Putin grew up and lives in a world that differs radically from that of the 1920s and 1930s. The people of the 21st century are not accustomed to the degree of violence that was considered normal 100 years ago, even in Europe. Society is much more open-minded and cosmopolitan now than it was in the years between World War I and II. The economies of nations are far more intertwined than they were in the early 20th century. It is very unlikely that Nazi-style fascism could thrive in today's world — and Putin is definitely not Hitler.

Some superficial parallels exist, but they only underscore how little modern authoritarian leaders resemble the bloodthirsty dictators of the past. Yes, Germany passed a law in 1933 "against forming new parties" that was enforced by the monopolistic Nazi Party, and those events somewhat resemble Putin's crackdown on the opposition. But after that law was passed, Germany created Dachau, the first concentration camp for political prisoners — something inconceivable in today's Russia. Germany also started persecuting homosexuals in 1935, but this was in the form of sending 15,000 to 20,000 of them to their deaths. In contrast, the entire "anti-gay" campaign in Russia led to nothing more than a few unlawful firings and beatings. Only someone who knows little of history can compare Hitlerjugend with Putin's Nashi movement.

Any comparison between Putin and Hitler is pointless, whether it focuses on Hitler before 1939 or the leaders' positive and negative qualities. But there is a more subtle comparison that deserves attention.

Putin came to power in 2000 presumably as a democrat, and he won the presidential election that year in a largely free and fair vote. But soon Putin introduced a new ideology according to which the state was superior to the individual, and national interests were much more important than private ones. This ideology was created for domestic use, but it has broad implications for Russia's neighbors as well.

The problem is not whether Putin is like Hitler, but how Putin's policies will eventually play out. His recent course will likely undermine the international norms and rules that existed when he came to power. Like Hitler before him, Putin has no new ideas on how to create a stable global system in place of the current one. He only wants to secure new territory as Hitler tried to guarantee a vast Lebensraum for the German people. And like Hitler, Putin appears unable — or lacking the desire — to stop advancing along his chosen path, however risky it may look.

Regrettably, the international community is unwilling or unable to stop the violation of human rights in Russia today, just as it was against Germany in the 1930s. Of course, the world was not legally obligated to intervene in the domestic affairs of a sovereign state — not in Hitler's Germany and not in Putin's Russia. But Putin's attempt to undermine the foundations of the international order is fraught with more serious consequences. Far from eliciting enthusiasm for Russia's politics, such actions only engender deep anxieties. Although Putin's domestic policies seem almost innocuous when compared to Hitler's, the effects of his foreign policy could prove equally disruptive to global stability.

When Putin argued that he annexed Crimea to protect ethnic Russians and Russian speakers — and not to defend Russian citizens — he effectively rewrote the rulebook of the second half of the 20th century that drew boundaries according to political and not ethnic affiliation. If this is allowed to continue, the consequences could be very serious.

The global community should halt Putin's attempt to undermine the principles and foundations of global security. He must be restrained and deterred by global leaders who are capable of ensuring stability in international affairs. Any attempt to confront Putin today would be much easier than it would have been to confront Hitler in the 1930s. If the West is incapable of controlling Putin, the global system will collapse within a few years. That is the most important lesson to be learned from any comparison between Nazi Germany and modern Russia.

Vladislav Inozemtsev is a professor of economics and director of the Moscow-based Center for Post-Industrial Studies.

A Message from The Moscow Times:

Dear readers,

We are facing unprecedented challenges. Russia's Prosecutor General's Office has designated The Moscow Times as an "undesirable" organization, criminalizing our work and putting our staff at risk of prosecution. This follows our earlier unjust labeling as a "foreign agent."

These actions are direct attempts to silence independent journalism in Russia. The authorities claim our work "discredits the decisions of the Russian leadership." We see things differently: we strive to provide accurate, unbiased reporting on Russia.

We, the journalists of The Moscow Times, refuse to be silenced. But to continue our work, we need your help.

Your support, no matter how small, makes a world of difference. If you can, please support us monthly starting from just $2. It's quick to set up, and every contribution makes a significant impact.

By supporting The Moscow Times, you're defending open, independent journalism in the face of repression. Thank you for standing with us.

Remind me later.