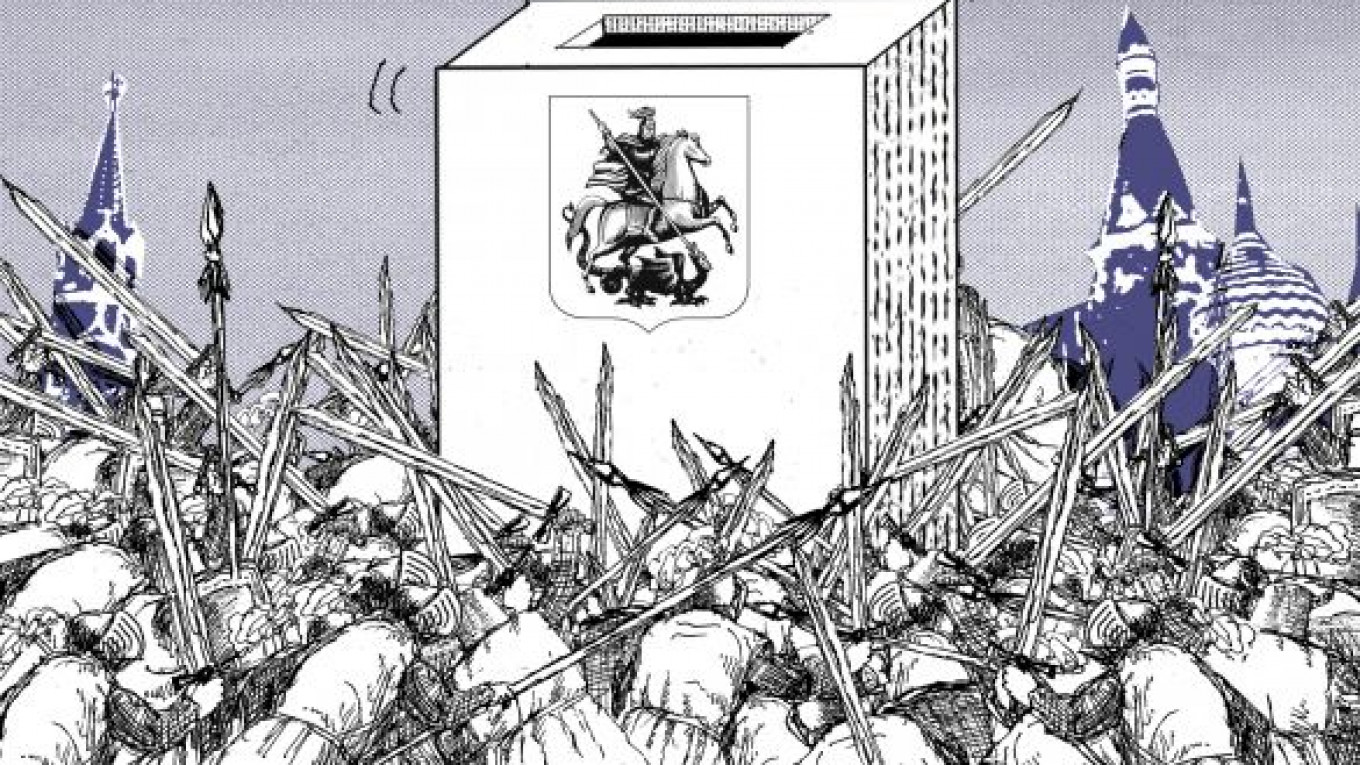

Today's most important political battle in Russia is not for control of the Kremlin but for power over its capital city. Indeed, the outcome of Moscow's mayoral election campaign concerns every Russian — and everyone who is interested in the country's fate.

Just as presidential elections in the U.S. matter for the entire world, mayoral elections in Moscow matter for Russia's national politics — and thus for its economy. So what happens in Moscow on Sunday — and possibly in the runoff election two weeks later if opposition leader Alexei Navalny gets a high percentage of the vote — will have profound implications for the country's future.

What happens in Moscow during the mayoral vote on Sunday will have profound implications for the country's future.

The election is a watershed for several reasons. For starters, this is the first Moscow mayoral campaign since President Vladimir Putin canceled gubernatorial elections in 2005. (They were reinstated in 2011 during Dmitry Medvedev's presidency.) Since the last mayoral election in 2004, Moscow has changed dramatically: It is now not only the largest and most important region in Russia — Moscow and St. Petersburg are classified as a federal regions, and thus the mayors of these cities are on the same level as governors— but Moscow is also a major European capital, a global business destination and a large consumer market.

Per capita income in Moscow is similar to that of Spain or Italy. The size of Moscow's city budget is close to that of New York city. Officially, 12 million people live in Moscow — not counting commuters and irregular immigrants — which is more than in an average European country. Yet before this year, Moscow's mayor was appointed by the federal government, not elected by Muscovites.

Second, the ongoing mayoral race is an unusually competitive election in Putin's Russia. The most important indication of this is the participation of Navalny — by far the Kremlin's most persistent political opponent. Navalny was registered as a candidate in the election and joined the campaign a day after being released from jail, following his conviction and five-year prison sentence in a clearly fabricated case.

Why the government first imprisoned him and then released him less than 24 hours later remains a mystery. What is clear is that the authorities want the Moscow mayoral election to be substantially more competitive than anyone expected it to be.

Third, thanks to Navalny's participation, the Moscow election has fostered — for the first time ever — genuine grassroots politics in Russia. Denied access to television, Navalny has carried out a U.S.-style door-to-door campaign. He has enlisted an unprecedented 15,000 volunteers and has raised an unprecedented $1.5 million from a diverse group of 8,000 Russians to finance his campaign.

Navalny's volunteers not only promote his message through social media. They also distribute his program and talk to voters in Moscow's streets and metro. Most impressive and completely unheard of in Russia, Navalny himself organizes three street rallies every weekday and five rallies on Saturdays and Sundays. His goal is to hold 100 such rallies by the end of the campaign.

Finally, Navalny's background and support base give him a level of moral authority with voters that other politicians in Putin's Russia cannot attain. Navalny's campaign is crowd-funded by ordinary Russians who understand that he is not on the payroll of a tycoon or the government.

Indeed, Navalny has been a persistent and effective critic of corruption in both the government and state-owned companies. Moreover, even though his e-mails have been hacked and published, and the government has searched his home and confiscated his computers and phones, there are no convincing charges against him — except for the blatant politically motivated cases. As a result, voters can be confident that Navalny, who refused to bow to legal intimidation, is clean and that he is running for the job not for his own material benefit or to do the bidding of any particular interest group, but because he believes in a greater good.

A campaign such as Navalny's certainly bodes well for Russia's future. Indeed, the absence of genuine political competition and the public's lack of confidence in Russia's politicians are the country's main problems because they undermine the rule of law, enable interest groups to "capture" state institutions and encourage corruption, all of which have led to capital flight and a brain drain. Thus, Navalny's growing support in Moscow is good news not only for Russians but also for foreigners who invest in Russia.

To be sure, there are still many reasons to be worried. Navalny certainly is not perfect, and although the Moscow election may be competitive by Russian standards, it is still outrageously unfair in terms of media access, financing and voter intimidation. Putin and United Russia did not win a majority in Moscow in the 2011 Duma election or the 2012 presidential election, but they seem confident of victory in the city this time. And Navalny's five-year prison sentence remains in place, pending an appeal whose outcome is completely uncertain.

Even so, what we are witnessing in Moscow far exceeds anyone's expectations. Win or lose, Navalny's campaign will have a lasting impact.

Sergei Guriev, a visiting professor of economics at Sciences Po, is professor of economics and former rector at the New Economic School in Moscow. He has been advising Alexei Navalny's mayoral campaign since going into exile in June. © Project Syndicate

A Message from The Moscow Times:

Dear readers,

We are facing unprecedented challenges. Russia's Prosecutor General's Office has designated The Moscow Times as an "undesirable" organization, criminalizing our work and putting our staff at risk of prosecution. This follows our earlier unjust labeling as a "foreign agent."

These actions are direct attempts to silence independent journalism in Russia. The authorities claim our work "discredits the decisions of the Russian leadership." We see things differently: we strive to provide accurate, unbiased reporting on Russia.

We, the journalists of The Moscow Times, refuse to be silenced. But to continue our work, we need your help.

Your support, no matter how small, makes a world of difference. If you can, please support us monthly starting from just $2. It's quick to set up, and every contribution makes a significant impact.

By supporting The Moscow Times, you're defending open, independent journalism in the face of repression. Thank you for standing with us.

Remind me later.