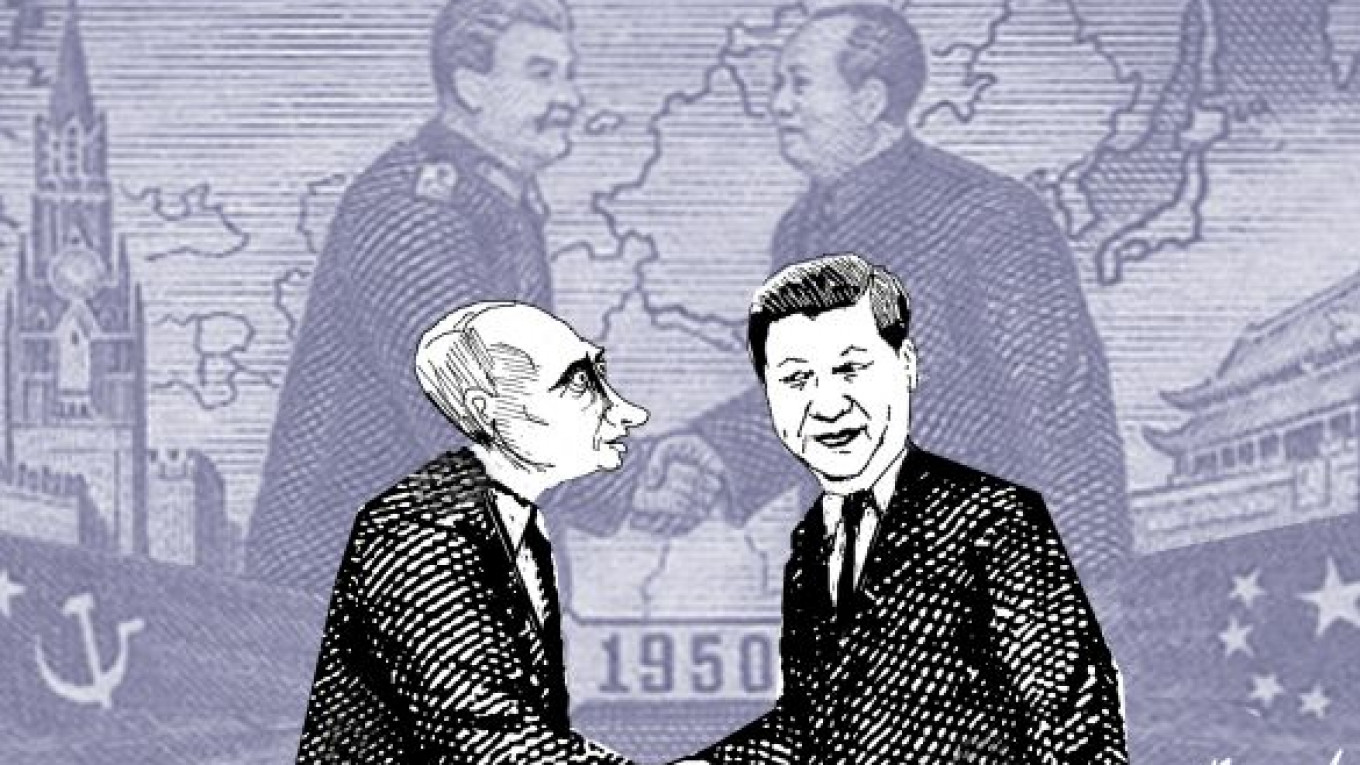

The atmospherics surrounding Xi Jinping's trip to Russia last month — his first visit to a foreign country as China's new president — reminded me of a slogan from my early childhood in the late 1950s: "Russia-China, Friendship Forever." The irony is that even in that slogan's heyday, Chinese-Russian relations were deteriorating fast, culminating in spasms of combat along the Amur River in Siberia less than a decade later. Is that slogan more valid now?

After China opened up its economy and Russia emerged from the Soviet Union, bilateral relations entered a new stage. Goodwill now prevails, but some of the old suspicions linger — and some new ones have emerged.

For starters, both the Russian and Chinese governments can afford to downplay the significance of their ties with the U.S. China views Russia as its strategic rear — and perhaps a base — in its escalating rivalry with the U.S. Russia's leaders view U.S.-Chinese competition as a welcome addition to their country's strategic weight, which, unlike China's, is not being augmented by robust economic growth. The more the U.S. challenges the inevitable expansion of China's "security perimeter," the better for Russia, or so the Kremlin's strategists appear to believe.

If Moscow doesn't develop a growth strategy for the Pacific region, the current Chinese-Russian entente will surely sour.

Meanwhile, the Chinese-Russian relationship has achieved an unprecedented degree of warmth. The Chinese are doing almost everything possible to placate Russian concerns. The old border disputes have been silenced. The volume of trade is growing rapidly.

Moreover, there has been no Chinese demographic expansion into Siberia, though many journalists and pundits have been peddling that story for years. The number of Chinese residing in Russia, whether officially or clandestinely, amounts to roughly 300,000. Many more Chinese lived in the Russian Empire before the 1917 revolution.

But beneath the surface, unease in the bilateral relationship persists, partly for historical reasons. Nationalist Chinese remember imperial Russia's conquests, while many Russians have a morbid fear of the "yellow peril," In reality, the Mongols conquered and reigned in China, while they were eventually repelled from Russia, not to mention that the Chinese never invaded Russia.

The more important reasons for the unease are the negative demographic trends in Russia's far-eastern Baikal region and the fear of overweening Chinese power, which is shared by all of China's neighbors. Indeed, the pundits have a point: If the current economic near-stagnation in Siberia persists, the world will witness a second, epic edition of Finlandization, this time in the east. That might not be the worst scenario a country could face, but it is not the most pleasant prospect for Russians, given their deeply ingrained sense of their status as a great power.

This scenario is not inevitable, but China is in the throes of an identity crisis as it faces an almost inevitable economic slowdown and the need to implement a new growth model.

Russia, meanwhile, is clearly suffering from an even deeper identity crisis. It somehow survived the post-Soviet shock and has now recovered. Yet for the last six years or so, Russia has been in a kind of limbo with no strategy, goals or elite consensus on a vision for the future.

For Chinese-Russian relations, such fundamental uncertainties may be a blessing. Both leaders can count on the other not to create additional problems and even to help passively on geopolitical questions. On Syria, for example, the two countries have shown that we are indeed living in a multipolar world. And those new oil and gas deals will buttress both economies.

In the long term, Chinese-Russian relations will depend largely on whether Russia overcomes its current stagnation and, among other steps, starts to develop the vast water and other resources of the Baikal region. To do so, capital and technology will be needed not only from China, but also from Japan, South Korea, the U.S. and Southeast Asian countries. The Baikal region could relatively easily expand ties with the resource-hungry Asian economies, to the benefit of all. Even the labor problem is solvable, with millions of workers from the former Soviet republics in Central Asia — and perhaps from a gradually liberalizing North Korea — able to take part in the ambitious development that will be needed.

But the first step is to start to create conditions in the region that make living and working there attractive to Russians. The Asia-Pacific Economic Cooperation summit in Vladivostok last year created a mere enclave of development. A growth strategy for the whole region is yet to come. If it does not, the current Chinese-Russian entente cordiale is almost certain to sour. Russia will start to feel vulnerable,and will be pushed toward either geopolitical brinkmanship or submission to China's will.

At this point, however, relations between China and Russia appear to be far better than the mythical friendship of my childhood. Putin and Xi should do everything to emphasize that.

Sergei Karaganov, honorary chairman of the presidium of the Council on Foreign and Defense Policy, is dean of the School of World Economics and International Affairs at Russia's National Research University Higher School of Economics. © Project Syndicate

Related articles:

A Message from The Moscow Times:

Dear readers,

We are facing unprecedented challenges. Russia's Prosecutor General's Office has designated The Moscow Times as an "undesirable" organization, criminalizing our work and putting our staff at risk of prosecution. This follows our earlier unjust labeling as a "foreign agent."

These actions are direct attempts to silence independent journalism in Russia. The authorities claim our work "discredits the decisions of the Russian leadership." We see things differently: we strive to provide accurate, unbiased reporting on Russia.

We, the journalists of The Moscow Times, refuse to be silenced. But to continue our work, we need your help.

Your support, no matter how small, makes a world of difference. If you can, please support us monthly starting from just $2. It's quick to set up, and every contribution makes a significant impact.

By supporting The Moscow Times, you're defending open, independent journalism in the face of repression. Thank you for standing with us.

Remind me later.