MADISON, Wisconsin — Soviet dictator Josef Stalin's daughter, whose defection to the West during the Cold War embarrassed the ruling communists and made her a best-selling author, has died. She was 85.

Lana Peters — who was known internationally by her previous name, Svetlana Alliluyeva — died of colon cancer on Nov. 22 in Wisconsin, where she lived off and on after becoming a U.S. citizen, Richland County Coroner Mary Turner said Monday.

Her defection in 1967 — which she said was partly motivated by the poor treatment of her late husband, Brijesh Singh, by Soviet authorities — caused an international furor and was a public relations coup for the United States. But Peters, who left behind two children, said her identity involved more than just switching from one side to the other in the Cold War. She even moved back to the Soviet Union in the 1980s, only to return to the States more than a year later.

When she left the Soviet Union in 1966 for India, she planned to leave the ashes of her late third husband, an Indian citizen, and return. Instead, she walked unannounced into the U.S. Embassy in New Delhi and asked for political asylum. After a brief stay in Switzerland, she flew to America.

Peters carried with her a memoir she had written in 1963 about her life in Russia. "Twenty Letters to a Friend" was published within months of her arrival in the United States and became a best-seller.

Upon her arrival in New York in 1967, the 41-year-old said: "I have come here to seek the self-expression that has been denied me for so long in Russia." She said she had come to doubt the communism she was taught growing up and believed that there weren't capitalists or communists, just good and bad human beings. She had also found religion and believed that "it was impossible to exist without God in one's heart."

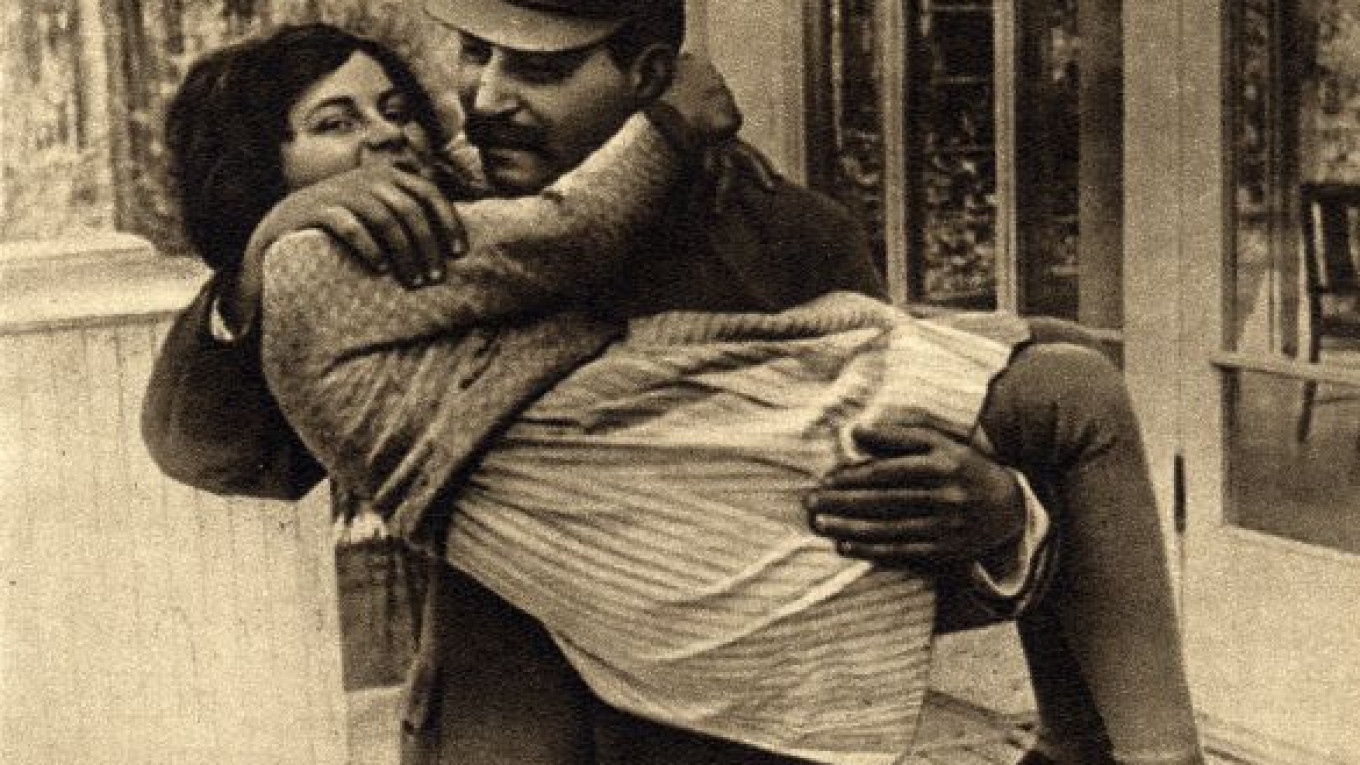

In the book, she recalled her father, who died in 1953 after ruling the nation for 29 years, as a distant and paranoid man.

"He was a very simple man. Very rude. Very cruel," Peters told the Wisconsin State Journal in a rare interview in 2010. "There was nothing in him that was complicated. He was very simple with us. He loved me, and he wanted me to be with him and become an educated Marxist."

Soviet Premier Alexei Kosygin denounced Peters as a "morally unstable" and "sick person."

"I switched camps from the Marxists to the capitalists," she recalled in a 2007 interview for the documentary "Svetlana About Svetlana." But she said her identity was far more complex than that and was never completely understood.

"People say, 'Stalin's daughter, Stalin's daughter,' meaning I'm supposed to walk around with a rifle and shoot the Americans. Or they say, 'No, she came here. She is an American citizen.' That means I'm with a bomb against the others. No, I'm neither one. I'm somewhere in between. That 'somewhere in between' they can't understand."

Peters' defection came at a high personal cost. She left two children behind in Russia — Josef and Yekaterina — from previous marriages. Both were upset by her departure, and she was never close to either again.

Raised by a nanny with whom she grew close after her mother's death in 1932, Peters was Stalin's only daughter. She had two brothers, Vasili and Jacob. Jacob was captured by the Nazis in 1941 and died in a concentration camp. Vasili died as an alcoholic at age 40.

Peters graduated from Moscow University in 1949, worked as a teacher and translator and traveled in Moscow's literary circles before leaving the Soviet Union. She was married four times — the last time to William Wesley Peters, an apprentice of Frank Lloyd Wright. They were married from 1970 to 1973 and had one daughter.

Peters wrote three more books, including "Only One Year," an autobiography published in 1969.

Her father's legacy appeared to haunt her throughout her life, though she tried to live outside of the shadow of her father. She denounced his policies, which included sending millions into labor camps, but often said other Communist Party leaders shared the blame.

"I wish people could see what I've seen," Lana Parshina, who interviewed Peters for "Svetlana About Svetlana," said Monday. "She was very gracious, and she was a great hostess. She was sensitive and could quote poetry and talk about various subjects. She was interested in what was going on in the world."

Charles E. Townsend, who was on the faculty at Princeton University's Department of Slavic Languages and Literatures when Peters arrived in Princeton in 1967, said she wasn't very politically active.

"She was very pleasant," Townsend said. "Unassuming would be the word for her."

After living in Britain for two years, Peters returned to the Soviet Union with Olga in 1984 at age 58, saying she wanted to be reunited with her children. Her Soviet citizenship was restored, and she denounced her time in the United States and Britain, saying she never really had freedom. But more than a year later, she asked for and was given permission to leave after feuding with relatives. She returned to the States and vowed never to go back to Russia.

She went into seclusion in the last decades of her life. Her survivors include her daughter Olga, who now goes by Chrese Evans and lives in Oregon. A son, Josef, died in 2008 at age 63 in Moscow, according to media reports in Russia. Yekaterina (born in 1950), who goes by Katya, is a scientist who studies an active volcano in eastern Siberia.

Evans said in an e-mail that her mother died at a Richland Center nursing home surrounded by loved ones, but she declined to comment further. "Please respect my privacy during this sad time," she said.

A Message from The Moscow Times:

Dear readers,

We are facing unprecedented challenges. Russia's Prosecutor General's Office has designated The Moscow Times as an "undesirable" organization, criminalizing our work and putting our staff at risk of prosecution. This follows our earlier unjust labeling as a "foreign agent."

These actions are direct attempts to silence independent journalism in Russia. The authorities claim our work "discredits the decisions of the Russian leadership." We see things differently: we strive to provide accurate, unbiased reporting on Russia.

We, the journalists of The Moscow Times, refuse to be silenced. But to continue our work, we need your help.

Your support, no matter how small, makes a world of difference. If you can, please support us monthly starting from just $2. It's quick to set up, and every contribution makes a significant impact.

By supporting The Moscow Times, you're defending open, independent journalism in the face of repression. Thank you for standing with us.

Remind me later.