As part of the Spanish-Russian year of cultural exchange, the Pushkin State Museum of Fine Arts on Friday opened its doors to the largest exhibition of Salvador Dali artworks in Russia.

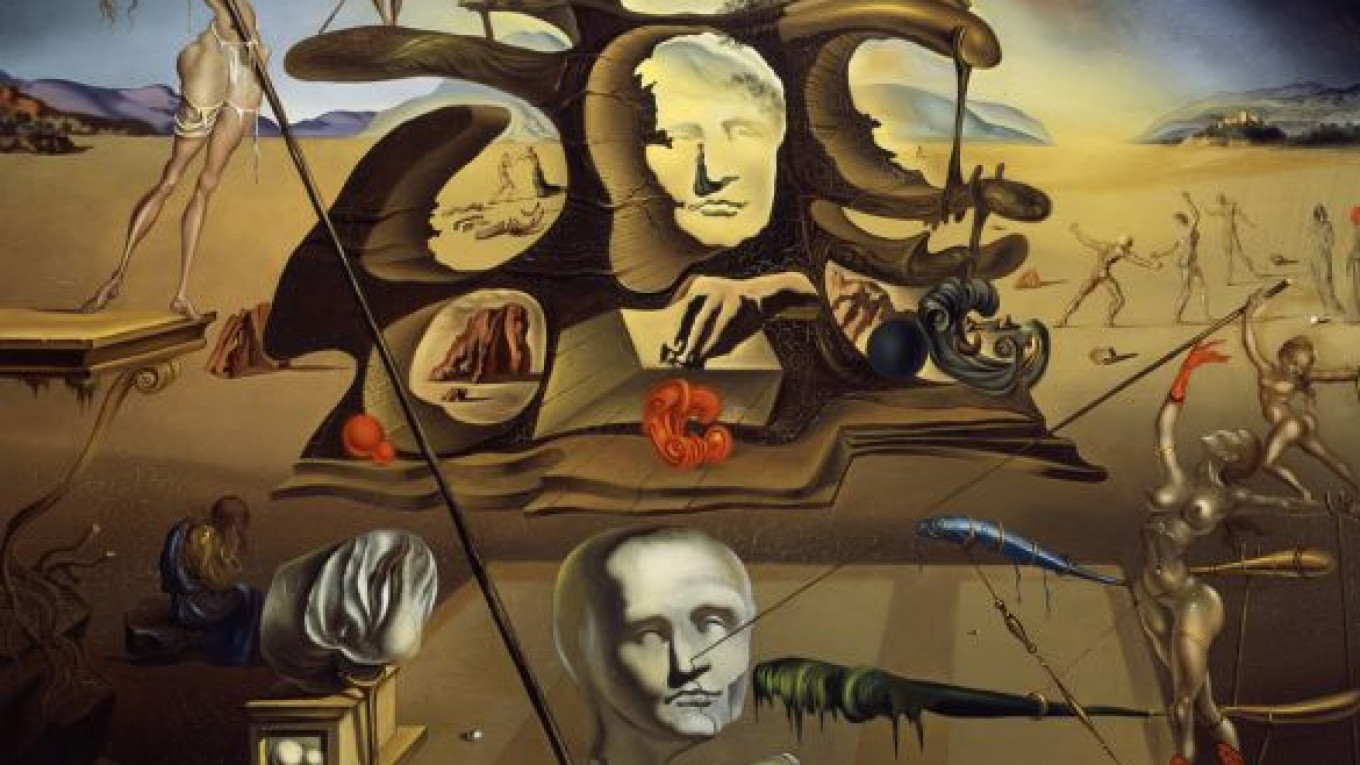

Until Nov. 13, “Salvador Dali: a Retrospective” showcases more than a hundred pieces, including 25 oil paintings, 20 watercolors, 70 drawings, and many personal items and photographs of the young Dali. “Napoleon’s Nose, Transformed Into a Pregnant Woman, Strolling His Shadow With Melancholia Amongst Original Ruins,” a surrealistic masterpiece drawn in 1945, is a centerpiece.

“Dali’s talent had many facets. He was a charismatic person who dared to make shocking statements. His personality corresponds to today’s information age. If Dali had not existed, we should have invented him,” curator Alexei Petukhov said in opening remarks.

The grand opening was attended by first lady Svetlana Medvedeva and Spanish Ambassador Luis Felipe Fernandez de la Pena.

The Gala-Salvador Dali Foundation provided the loans, part of the collection of the Teatro-Museo Dali in the artist’s rural hometown, Figueres, Spain. The Teatro-Museo is a former town theater that Dali remodeled in 1974 and, as he wished, contains his crypt.

“I needed to travel to Dali’s roots, and I was indeed inspired by the artist’s hometown and birthplace, and the incredible setup of the Teatro-Museo,” said designer Boris Messerer, when asked about his inspiration for the show’s layout.

Meant to evoke the feeling of entering Dali’s surrealistic world, Messerer’s design places giant egg sculptures along the stairs leading to the two main exhibition rooms. In one room, a film of the artist’s life is screened.

The retrospective begins with works Dali created in his 20s. An idee fixe is Dali’s wife and longtime muse, Gala. She appears in many of the oil paintings and aquarelles.

Born Yelena Dyakonova in Kazan, Gala traveled to Switzerland in 1913, where she met her first husband, French surrealist poet Paul Eluard. In 1929, the couple traveled to Spain to meet an aspiring young painter — 25-year-old Dali. After a longtime affair, Dali and Gala wed in 1934.

“Portrait of Gala With Two Lamb Chops Balanced on Her Shoulder” epitomizes Dali’s particular love for Gala as well as for detail. A miniature, 6-by-8-centimeter canvas reveals an intricate beauty — to the closely standing observer.

Gala is Dali’s special link to Russia, and even though he never spoke his wife’s mother tongue, he enjoyed the sound of the language and asked Gala to read to him in Russian.

Dali was born Salvador Domingo Felipe Jacinto Dali i Domenech on May 11, 1904, in the small agricultural town of Figueres. He attended the San Fernando Academy of Fine Arts in Madrid, and early recognition of his talent came with his first solo show in Barcelona in 1925.

Though Dali was one of the main figures in the surrealistic movement, his political clashes with other surrealists led to ostracism in 1934. During World War II, Dali and Gala emigrated to the United States, where they lived until 1948.

After the war, the couple returned to Spain, where Dali began to employ more religious and scientific themes in his work.

“Dali is special to the art world because he’s an artist of the modern age. His whole life was an art object in itself,” curator Petukhov told reporters.

Pushkin Museum director Irina Antonova emphasized the friendly cooperation between the Russian and Spanish museums that made the project possible, and noted that Russian visitors to the Dali museum in Figueres have for years been one of the largest international groups.

“Salvador Dali: a Retrospective” is on show until Nov. 13 at the Pushkin State Museum of Fine Arts, 12 Ulitsa Volkhonka. Metro Kropotkinskaya. Tel. 697-9578, .

A Message from The Moscow Times:

Dear readers,

We are facing unprecedented challenges. Russia's Prosecutor General's Office has designated The Moscow Times as an "undesirable" organization, criminalizing our work and putting our staff at risk of prosecution. This follows our earlier unjust labeling as a "foreign agent."

These actions are direct attempts to silence independent journalism in Russia. The authorities claim our work "discredits the decisions of the Russian leadership." We see things differently: we strive to provide accurate, unbiased reporting on Russia.

We, the journalists of The Moscow Times, refuse to be silenced. But to continue our work, we need your help.

Your support, no matter how small, makes a world of difference. If you can, please support us monthly starting from just $2. It's quick to set up, and every contribution makes a significant impact.

By supporting The Moscow Times, you're defending open, independent journalism in the face of repression. Thank you for standing with us.

Remind me later.