Liberal politician Vladimir Ryzhkov in his comment on these pages on Tuesday made a convincing argument that the Egyptian scenario is not applicable to Russia — mainly because of stark demographic, religious and cultural differences between the countries. But this is no reason for the Kremlin to rest assured. The million-strong protests in Egypt demanding that President Hosni Mubarak step down and last month’s uprising in Tunisia serve as important reminders to the Kremlin of how vulnerable an autocracy is to a coup.

Despite the differences, there are still many parallels between Russia, Tunisia and Egypt: a monopolization of political power, a low per capita gross domestic product, limited economic opportunities, human rights abuses, a lack of free elections and restricted media freedoms, rampant corruption and nepotism, and a huge gap between the rich and poor with an insignificant middle class.

Mubarak served 29 years in office, and former Tunisian President Zine El Abidine Ben Al was in power for 23 years — the same number of years Putin will be in power, assuming he remains national leader (whether president or prime minister) for the next two presidential terms.

The Tunisian street protests started in December when a 27-year-old street vendor set himself on fire. He died several weeks later from his injuries. Notably, his chief complaint was that corrupt police expropriated his goods when he refused to pay bribes. Sound familiar?

The Tunisian revolution differs little from all the other revolutions against corrupt autocratic regimes, whether it be the 1986 overthrow of Philippine President Ferdinand Marcos, the multiple anti-Communist revolutions in 1989 in Eastern Europe, the 1998 uprising in Indonesia that forced President Suharto to resign or the ouster of Kyrgyz President Kurmanbek Bakiyev in April.

Since World War II, more than 125 authoritarian regimes have collapsed. There are 55 autocracies left, according to the Democracy Index. Despite all the hype last year among political analysts about the so-called fading of Western democracy and the rise of the autocratic model (read: China and Singapore), history is not on autocracy’s side. For every China and Singapore, there are many more Suhartos, Marcoses and Mubaraks, whose regimes last about 30 years before they collapse.

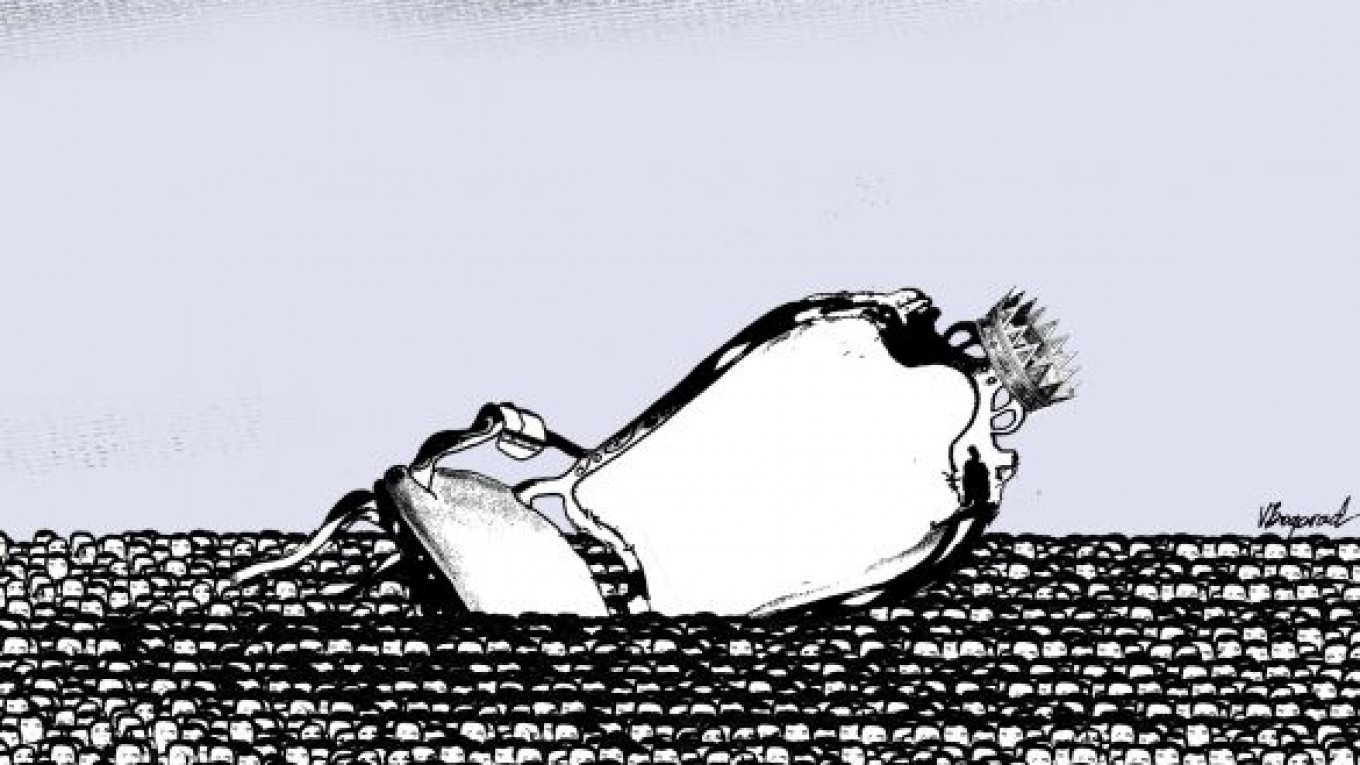

Because autocracies, by definition, lack legitimacy, they are inherently unstable. When millions of people finally reach their boiling point and take their anger onto the streets, there will never be enough police or soldiers to repress popular movements demanding basic liberty, freedoms and economic opportunity, especially when the police and soldiers share the same complaints.

The pensioners’ protests in 2005 and the 10,000-strong protest in Kaliningrad a year ago were Russia’s first serious wake-up calls during Vladimir Putin’s 10-year reign. These protests, of course, were mild compared with Egypt and Tunisia, but Russian protests could easily intensify if there is a sharp rise in inflation, for example, and if corruption and lawlessness continue unabated while the people’s standard of living continues to fall.

Russia differs little from other autocracies that have a small layer of corrupt and extremely wealthy political and business elite, a large lower class and a miniscule middle class that is crucial to provide a political, social and economic buffer. As long as the Russian elite continue to build mansions — both at home and abroad — while millions of Russians have trouble making ends meet with monthly incomes of $500 or less, this is a ticking time bomb for social unrest and street protests.

The Kremlin is making the same mistakes that all fallen autocratic regimes have made. By controlling the main media, manipulating elections and excluding opposition forces from the political process, Russia’s leaders can easily radicalize the people. As Elliot Abrams wrote in a Jan. 20 comment in The Washington Post, “Regimes that make moderate politics impossible make extremism far more likely.”

Indeed, as history often shows, when living conditions become intolerable under autocracies and people have no hope for the future, they first hit the streets with banners and slogans. If this doesn’t work, they return with Molotov cocktails.

The Manezh rioting in December and the weekly killings of policemen in the North Caucasus are two examples of how hopelessness and anger can turn into violence and extremism. This is inevitable when there are no other civil mechanisms available to bring about change in an ossified kleptocracy that is unwilling to reform itself or break its monopolistic hold on power.

Let’s hope the Kremlin draws the correct lessons from the Jasmine Revolution in Tunisia and the unrest in Egypt. Of course, Russia is under no immediate threat of revolution, and this has led the country’s leaders to become complacent with the status quo. It seems that the Kremlin under Putin’s leadership believes that Russians will tolerate low standards of living, corruption and government abuses forever. But, then again, so did Suharto, Marcos, Mubarak, Ceausescu and all of history’s other fallen autocrats.

A Message from The Moscow Times:

Dear readers,

We are facing unprecedented challenges. Russia's Prosecutor General's Office has designated The Moscow Times as an "undesirable" organization, criminalizing our work and putting our staff at risk of prosecution. This follows our earlier unjust labeling as a "foreign agent."

These actions are direct attempts to silence independent journalism in Russia. The authorities claim our work "discredits the decisions of the Russian leadership." We see things differently: we strive to provide accurate, unbiased reporting on Russia.

We, the journalists of The Moscow Times, refuse to be silenced. But to continue our work, we need your help.

Your support, no matter how small, makes a world of difference. If you can, please support us monthly starting from just $2. It's quick to set up, and every contribution makes a significant impact.

By supporting The Moscow Times, you're defending open, independent journalism in the face of repression. Thank you for standing with us.

Remind me later.