President Dmitry Medvedev on Monday met with his human rights council for the second time this year, a week after the death of a lawyer jailed in a politically tinged tax case drew widespread condemnation from rights groups.

The council meeting focused on NGOs, corruption and the legal system, Dmitry Oreshkin, a political analyst and member of the 35-member council, told The Moscow Times.

The advisory group, created under then-President Vladimir Putin, has enjoyed a more prominent role in Medvedev’s Kremlin, but it is less critical of the government than independent rights groups.

Ella Pamfilova, the group’s head, drew attention to the death of lawyer Sergei Magnitsky, calling it “a murder and a tragedy.” She also said an online video appeal to Prime Minister Putin, recorded earlier this month by police major Alexei Dymovsky, and a series of copycat recordings showed that the law enforcement system needed serious reform.

In his opening remarks, Medvedev highlighted his efforts to improve conditions for nongovernmental organizations but made no direct mention of the issues that have most concerned Russian rights activists. He also reminded members that the proceedings would be recorded and later posted for public access.

Magnitsky, 37, was a partner at the Firestone Duncan law firm. He was accused of being directly involved in developing and executing a tax-evasion scheme with William Browder, head of the Hermitage Capital investment fund, once Russia’s largest foreign investor.

The Interior Ministry said Nov. 17 that he died of apparent heart failure and toxic shock, and results of an autopsy are pending. Magnitsky’s lawyers and colleagues say he was repeatedly denied medical attention and was kept in inhuman conditions for almost a year without trial.

Browder said in an interview with the BBC on Monday that Magnitsky was killed like a hostage in jail, and that Russia was now a “criminal state.” Browder was banned from Russia as a threat to the health or security of the state in 2005 after accusing Interior Ministry officers of stealing more than $230 million in budget funds.

“It has become almost a professional sickness of Russian entrepreneurs,” Pamfilova said, referring to the frequency with which people die in custody, Interfax reported.

“One of the presentations mentioned that the acquittal rate in Russian courts is less than 1 percent. The president seemed surprised and promised to look into it,” Oreshkin said.

Pamfilova also spoke about Dymovsky, who was promptly sacked from the Novorossiisk police force for slandering his superiors, and the wave of complaints from other officers about abuses of authority, illegal arrests and poor working conditions.

“The Dymovsky incident, or syndrome, without reference to the major’s personality, is just a confirmation of the diagnosis for the whole law enforcement system,” Pamfilova said, Interfax reported.

The major recorded a series of videos and held numerous press conferences and interviews earlier this month, but police and former colleagues have sought to downplay his accusations with attacks on his character.

Medvedev did not promise any immediate reaction to either the Magnitsky or Dymovsky cases.

Others noted that those who are supposed to fight corruption are often its biggest promoters, Oreshkin said. Medvedev agreed that such problems cannot be solved quickly, he said.

More broadly, the meeting comes during a bad year for the Interior Ministry, which has found itself justifying the promotion of a well-connected major who later went on a shooting rampage; its need to purchase a gold-lined bed; and most recently, the arrest of Magnitsky.

Medvedev said a bill to support socially oriented NGOs would be submitted to the State Duma. In the state-of-the-nation address Nov. 12, Medvedev said NGOs working on social problems should receive wide state support, including financially. “The bill has been prepared, I’ve already signed off on it,” Medvedev said. It was submitted to lawmakers later Monday.

He also said 1.2 billion rubles ($42 million) in budget funding has been provided to the noncommercial sector this year, and that Russian troops involved in last year’s war with Georgia would be recognized as combatants, which would allow them to receive certain benefits.

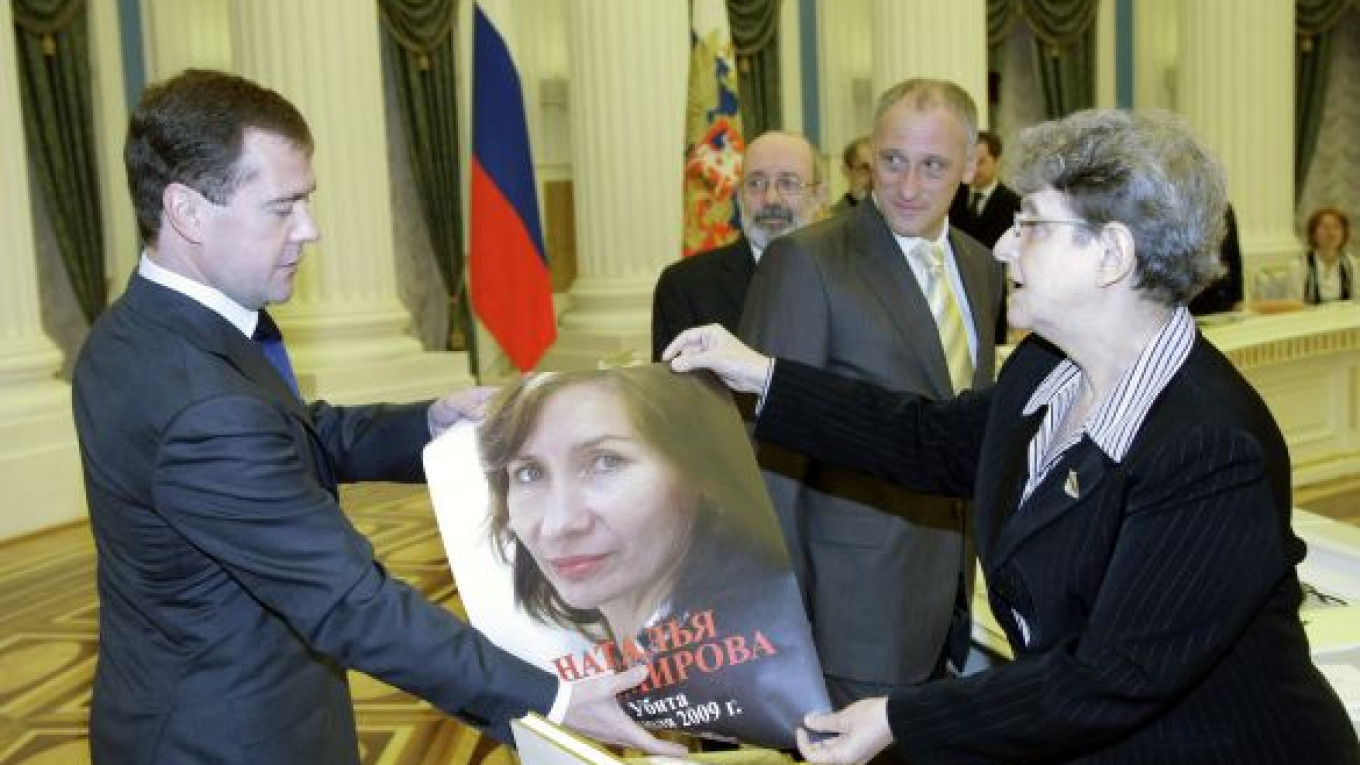

The president backed the council’s initiative to hold a separate meeting focused on the situation in the Caucasus, where a number of human rights activists were killed this summer, including Natalya Estemirova, a member of Memorial’s branch in Chechnya.

Svetlana Gannushkina, another member of the council, gave Medvedev a poster of Estemirova with her name and the words: “Murdered, July 2009.”

Medvedev also suggested that more experts working in the country’s violent south be invited to the meeting.

“I don’t expect much of such meetings, and I don’t get too worked up about the aftermath. But it’s important that [Medvedev] receives some information from independent sources,” Oreshkin said.

Due to time constraints, only about 12 of the 18 planned reports from council members were presented Monday, he said.

Pamfilova and the council came under fire in October after criticizing a harassment campaign by the pro-Kremlin Nashi youth group against journalist and human rights activist Alexander Podrabinek, who wrote critically of a World War II veterans group.

A number of State Duma deputies and senior United Russia officials demanded Pamfilova’s resignation, but the Kremlin signaled that it supported her and Nashi eventually dropped their demonstrations outside Podrabinek’s home.

A Message from The Moscow Times:

Dear readers,

We are facing unprecedented challenges. Russia's Prosecutor General's Office has designated The Moscow Times as an "undesirable" organization, criminalizing our work and putting our staff at risk of prosecution. This follows our earlier unjust labeling as a "foreign agent."

These actions are direct attempts to silence independent journalism in Russia. The authorities claim our work "discredits the decisions of the Russian leadership." We see things differently: we strive to provide accurate, unbiased reporting on Russia.

We, the journalists of The Moscow Times, refuse to be silenced. But to continue our work, we need your help.

Your support, no matter how small, makes a world of difference. If you can, please support us monthly starting from just $2. It's quick to set up, and every contribution makes a significant impact.

By supporting The Moscow Times, you're defending open, independent journalism in the face of repression. Thank you for standing with us.

Remind me later.