Russia’s party system developed in a decidedly lopsided way during the 2000s. As with all things lopsided, it runs a serious risk of instability, which could occur over the next decade. Understanding how this is the case requires clearing up four common myths about political parties in Russia.

Myth No. 1. United Russia is an empty shell, constituting nothing more than a collection of ambitious elites with no genuine ties to the population. Public opinion surveys show this to be false. Take, for example, the Russian Election Studies surveys, which I co-organized. Not only can one fairly count over a quarter of the country?€™s electorate as party loyalists as of 2008, but the party also connects clearly in public minds with important issues, such as a generally market-oriented approach to the economy.

While United Russia?€™s support is also closely linked with its leader, Prime Minister Vladimir Putin, this is far from the whole story. Indeed, part of Putin?€™s appeal is linked to issues — many of them the same ones identified with United Russia ?€” as well as with a general “Putinist” style of leadership that in principle can be practiced by others. This strongly suggests that were Russia to open up its political system now, United Russia could not only survive but potentially thrive with good leadership. Comparative analysis shows that even highly personalistic parties can survive their initial leaders ?€” for example, the Peronists in Argentina.

Myth No. 2. There is no viable opposition in Russia. Many claim that the Kremlin-sanctioned Communist Party is allowed only because it is unelectable, which means it can never inject real competition into the system. True, in its current form and under its current leadership, it is hard to imagine it ever winning the presidency or a parliamentary majority. It is too closely associated with a past that is too widely discredited. But parties can reform. Who would have thought in 1989 that former Communist parties could return to power in Eastern Europe? But they soon did even in Poland, birthplace of the Solidarity movement, and in Lithuania, a country that led the charge to bring down the Soviet Union.

The Communist parties were able to rebound because they reformed. They became something like classic European social democratic or labor parties. Some say that Russia?€™s Communist Party could not pull off such a feat, but a determined effort to reform the party, to shed discredited symbols and join the ranks of social democratic parties has the potential to succeed over the next decade should the right leader emerge. This could place it in position to reap the gains should the Kremlin and United Russia make major missteps by 2020.

Many believe that Yabloko, arguably the only other Kremlin-sanctioned opposition party after the Communist Party, has no chance to win. Surely this is true for 2011-12. Marginalized parties do have the chance to rise to power once the ruling regime weakens, and this can happen suddenly. Take Mexico in 2000. The PRI party, which had ruled seemingly unchallenged for decades, fell victim to economic problems and before it knew what happened, the formerly minor PAN party rose to capture the presidency under a renewed leadership that seemed fresher than the incumbents. Neither Grigory Yavlinsky nor Sergei Mitrokhin are likely the figures to lead Yabloko to the promised land. But if it can survive over the next 10 years, its relatively clean reputation make it the most likely potential winner should United Russia and its patrons lose their footing and should the Communist Party fail to reform.

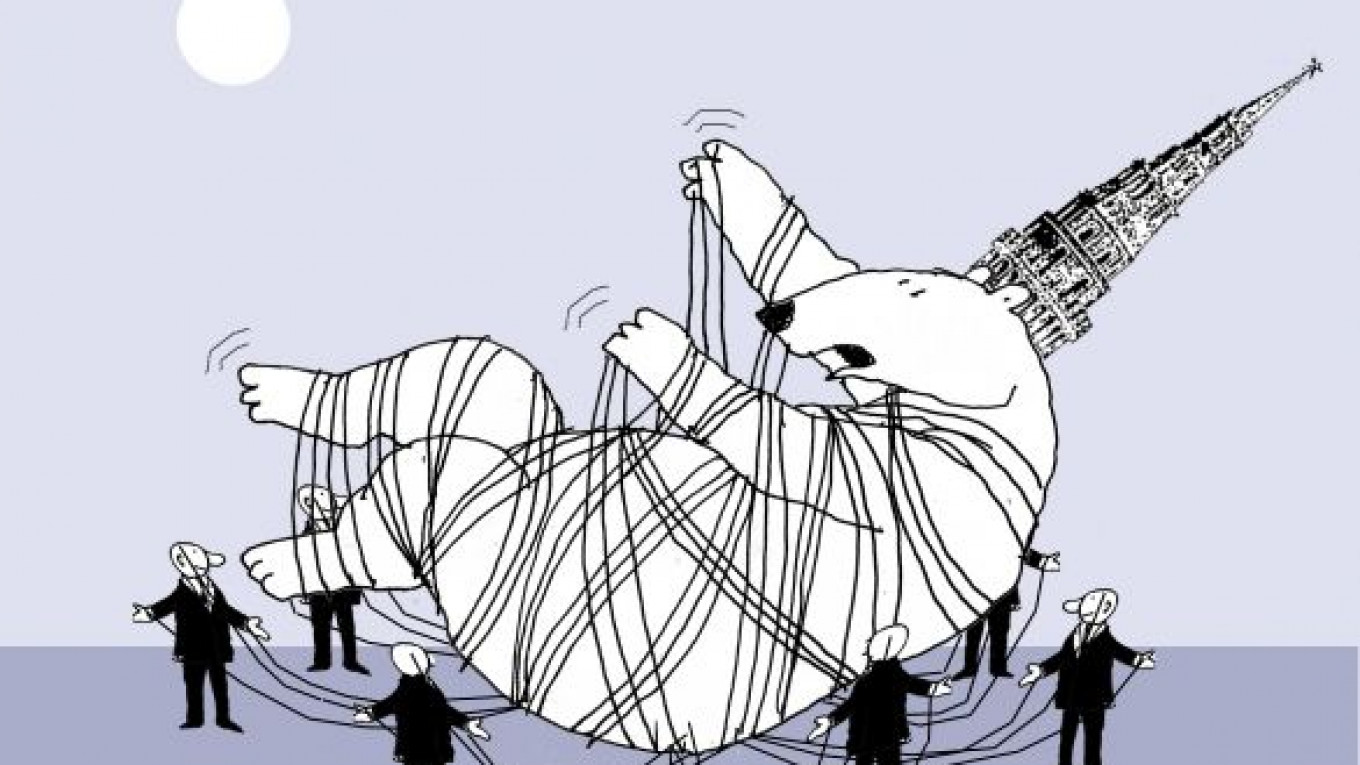

Myth No. 3. All the other parties are ?€?virtual parties?€? that have no prospects whatsoever except as tools for the Kremlin. This is a myth with a grain of truth behind it. But history shows that political puppets can take on lives of their own when the puppeteer himself loses control. Virtual parties typically contain many ambitious figures who are trying to use the Kremlin as much as the Kremlin is using them.

Should the Kremlin falter, with United Russia and its patrons dropping in popularity and the springs of the political machine flying off, these ambitious figures are unlikely to sacrifice their own ambitions. Instead, they are likely to try to use the resources they have at their disposal to take the puppeteer?€™s place. Recall the battle for Stavropol region in 2007, when pro-Kremlin parties were given the green light to battle each other relatively freely for local authority: Quite a struggle emerged between United Russia and A Just Russia, one prompting the Kremlin to quickly switch the light back to red. What happens when the Kremlin is no longer in such a strong position?

Myth No. 4. The liberal opposition that is not sanctioned by the Kremlin, such as Parnas, has no hope of coming to power in Russia in the next 10 years. The current authorities will most likely continue to keep the Garry Kasparovs, Mikhail Kasyanovs, Boris Nemtsovs and Vladimir Ryzhkovs out of power. But by continuing to restrict competition as tightly as it now does, the Kremlin over the next decade or two risks its own ?€?Arab Spring,?€? which means a transition over which it has much less influence. Recall that Hosni Mubarak?€™s ruling National Democratic Party seemed to be even stronger than United Russia in 2010, but it completely vanished by mid-2011.

In politics as in sports, champions are often better off going out while on top, while they can still shape their own graceful exit. But they rarely do.

Henry Hale is associate professor of political science and international affairs at The George Washington University. This comment appeared in Vedomosti.

A Message from The Moscow Times:

Dear readers,

We are facing unprecedented challenges. Russia's Prosecutor General's Office has designated The Moscow Times as an "undesirable" organization, criminalizing our work and putting our staff at risk of prosecution. This follows our earlier unjust labeling as a "foreign agent."

These actions are direct attempts to silence independent journalism in Russia. The authorities claim our work "discredits the decisions of the Russian leadership." We see things differently: we strive to provide accurate, unbiased reporting on Russia.

We, the journalists of The Moscow Times, refuse to be silenced. But to continue our work, we need your help.

Your support, no matter how small, makes a world of difference. If you can, please support us monthly starting from just $2. It's quick to set up, and every contribution makes a significant impact.

By supporting The Moscow Times, you're defending open, independent journalism in the face of repression. Thank you for standing with us.

Remind me later.