Dec. 26 marks 200 years since the Decembrist uprising in St. Petersburg. Liberal army officers, inspired by Western ideals after defeating Napoleon, tried to prevent Tsar Nicholas I from taking the throne. They demanded a constitution and the abolition of serfdom. “Law and liberty,” they cried.

In liberal historical memory, the Decembrists are often held up as proof that another Russia is possible. When the moment of Vladimir Putin’s succession comes, liberals posit, the regime will be at its most vulnerable to change.

But if that future Russia does come to pass, it will not look the way either today’s liberals or the Decembrists imagined.

Some remember the Decembrists as honorable and self-sacrificing; others as traitors. Many historians see them as naive dreamers who delayed reform and made the system they despised even more draconian. That they also inspired Lenin and Trotsky, not to mention later Soviet dissidents, only adds to the paradoxes.

The reality is that the Decembrists were a fragmented group of liberal-minded nobles operating in different parts of the empire. They had competing priorities, little in common with the broader population and only a half-formed plan to seize power from the ancien régime. They were happiest reciting poetry and performing rituals in Masonic lodges.

Then, in 1825, they attempted to take advantage of an unclear royal succession — and failed.

Nonetheless, “a beginning was made,” argued a recent piece in The Economist. At best, the revolt put the state on notice and sped up conversations about Russia’s need for reform. Ideas of civic consciousness began to solidify, defined by honor, dignity, power-sharing, freedom and justice.

But this was not the beginning of liberal reform in Russia. That began 149 years earlier — a fact that exposes a historical blind spot in Russia’s liberal imagination.

Most of Russia’s successful liberal reforms have actually come from an autocratic state trying to reform itself. Attempted coups and uprisings are common throughout Russian history, but few achieved lasting results. The Decembrists are remembered largely because their legacy endured, making them something of an exception among Russia’s many failed revolts.

The self-described democrats of the 1990s owed their rise to Mikhail Gorbachev. There would have been no Boris Yeltsin without him. This is just one of many examples in which an autocrat initiated reform, whether to liberalize, modernize or secularize the state.

Besides Gorbachev and Yeltsin, Alexander II, Catherine the Great and Peter the Great stand out as rulers who enacted durable change. Several others, like Nikita Khrushchev, Nicholas II, Alexander I and Paul I, tinkered with reforms around the edges. None were democrats, nor did they represent the beginning of reform.

Russia’s first true reformer is a largely forgotten figure. He, too, was an autocrat. He ruled for just eight years and died at the age of 20. Chronically ill and severely disabled from childhood, he was succeeded by his brother, Peter the Great, who would later force westernization onto the empire. This reformer was Feodor III.

Feodor, who believed Russia belonged in Europe alongside its great powers, introduced a range of liberal reforms with minimal opposition or attempts to reverse them. He was neither controversial nor especially revered.

Today, he is best known for his reforms to education and to civil and military service. He set up the Academy of Sciences and the Slavic Greek Latin Academy, moving Russia closer to European educational standards. Access to education expanded, and all subjects were mandated by law. This included those forbidden by the Orthodox Church, like geometry, science and Polish.

In 1682, Feodor abolished the old appointments system known as mestnichestvo. Jobs in the civil service and military would be assigned on merit with final approval by the tsar. Positions were no longer guaranteed as a right of birth or social status. The nobility books, known as the pedigree, were destroyed to prevent false claims to privilege.

Feodor also softened penal laws, reducing the use of harsher punishments and extended sentences. State meetings took on a less oppressive atmosphere. Those who knew the tsar found him to be kind — perhaps shaped by his own physical fragility.

He had plans for further reforms, but time was running out and he knew it. Like many reformers in history, he rushed changes through in the hope they would take root. This pattern has had mixed results.

The Decembrists had similar goals to Feodor. They wanted Russia to join and emulate Europe. They desired education reforms, a non-corrupt and non-draconian political system, not to mention accountability and economic freedoms. So what went wrong?

For one thing, the Decembrists didn’t expect to succeed. Their designated leader, Sergei Trubetskoy, never even showed up at Senate Square to challenge Nicholas I. They were extremely disorganized — sound familiar, Russian democrats? — with conflicting end goals and little thought given to what would come after they carried out their quickly hatched plan. It’s also plausible that the new tsar would have been receptive to some of their ideas, had they not tried to overthrow and possibly kill him.

Autocratic governments, by contrast, command vast resources and can push on with their agendas. Officials can be whipped into line or replaced at a whim. The population has historically welcomed reforms, as well. The rebellions tend to come from within the state itself. As long as these groups have limited popular support, they can be dealt with.

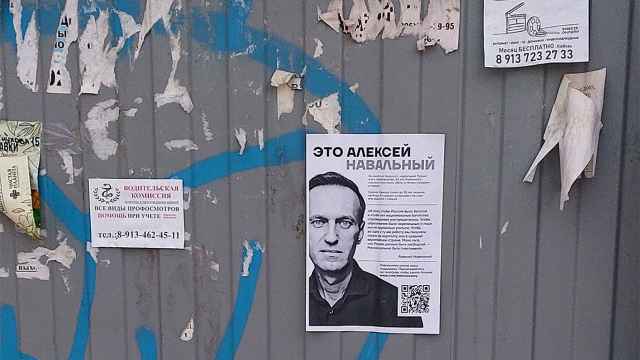

The uncomfortable lesson for Russia’s divided liberal opposition, 200 years later, is that another Russia might only be possible when the right leader emerges from within the state system. A Feodor the Forgotten, rather than another failed revolt. Rebellions tend to set reforms back and lack widespread support. Anti-Putin protests have been followed by greater crackdowns, just like what followed the Decembrists’ revolt.

There is no reason a reformer cannot succeed Vladimir Putin in time, if not immediately. History tells us that this is the best hope for a liberal Russia. In the meantime, the opposition would do well to think seriously about what that future will look like — and to ground their vision in reality rather than their dreams.

If a reformer emerges from within the current regime, it would be unwise to trash their efforts, lest it backfire. The Russian people’s first priority is their standard of living. Problems persist, but memories of better days gravitate to life before the war, a period that had little to do with democracy.

A different future is possible, but it must be a gradual process. If future reforms don’t deliver tangible improvements, the old ways will prevail. Russia’s people will remain disillusioned and apathetic. Russia’s democrats appear largely oblivious to that reality.

A Message from The Moscow Times:

Dear readers,

We are facing unprecedented challenges. Russia's Prosecutor General's Office has designated The Moscow Times as an "undesirable" organization, criminalizing our work and putting our staff at risk of prosecution. This follows our earlier unjust labeling as a "foreign agent."

These actions are direct attempts to silence independent journalism in Russia. The authorities claim our work "discredits the decisions of the Russian leadership." We see things differently: we strive to provide accurate, unbiased reporting on Russia.

We, the journalists of The Moscow Times, refuse to be silenced. But to continue our work, we need your help.

Your support, no matter how small, makes a world of difference. If you can, please support us monthly starting from just $2. It's quick to set up, and every contribution makes a significant impact.

By supporting The Moscow Times, you're defending open, independent journalism in the face of repression. Thank you for standing with us.

Remind me later.