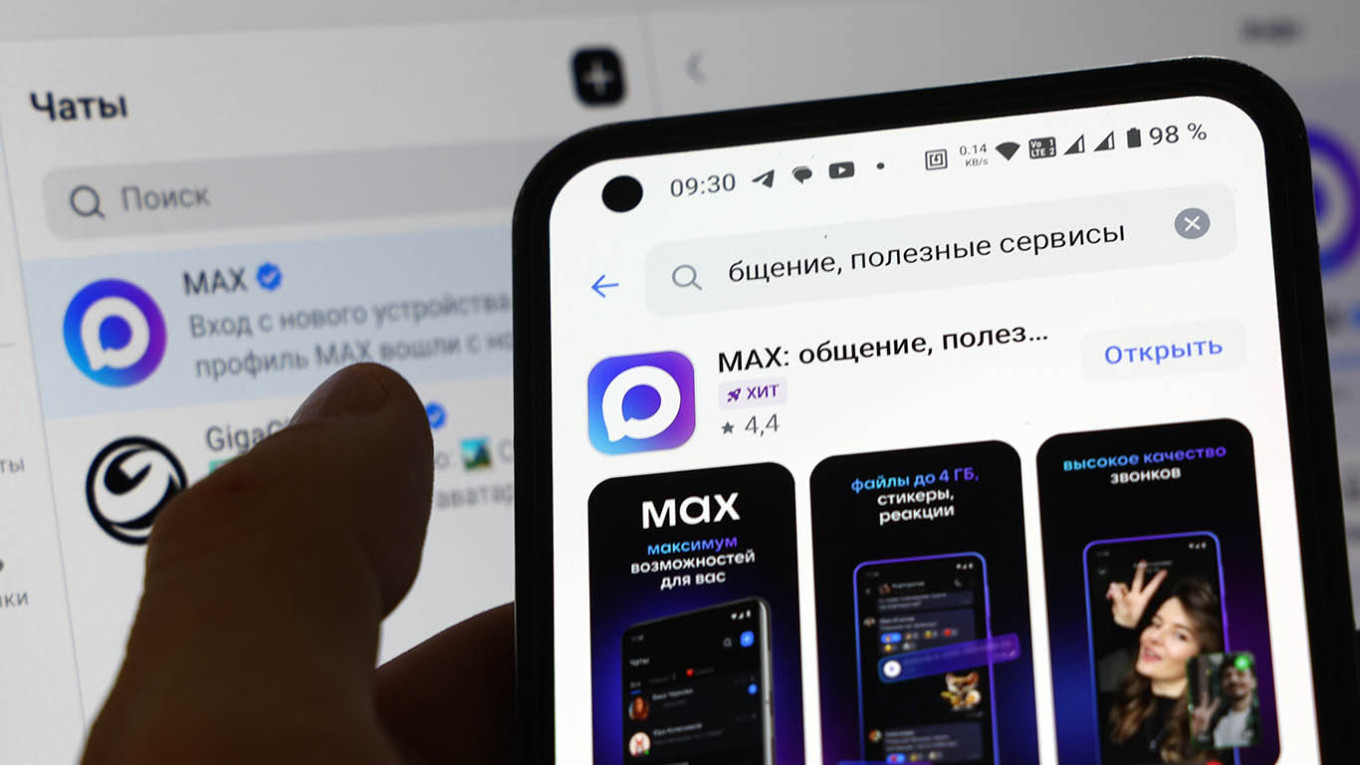

Russia's latest attempt to build a sovereign digital ecosystem is moving into high gear. Max, a state-backed messenger developed by VK, is being positioned as a patriotic alternative to WhatsApp and Telegram — platforms that in recent weeks have suffered complete or partial disruptions to voice and video calls across the country.

Officials say Max will soon become Russia's "super-app": a single platform for messaging, payments and government services.

Launched in March, the app already claims more than 18 million registered accounts compared to just 1 million in June.

We delved into the app's functionality, its vulnerabilities and the government's turbo-charged effort to make Max into what it claims it to be:

Connectivity where others fail

Starting Sept. 1, Max must come pre-installed on all smartphones, tablets, computers and smart TVs sold in Russia.

The Kremlin's timing could hardly be more deliberate. Since mid-August, users of WhatsApp and Telegram have been unable to make voice calls, with connections either failing immediately or dropping within seconds.

Roskomnadzor officially blocked voice calling features in both messengers, citing their use by scammers and terrorists, though the move has affected ordinary citizens who relied on these services to save on cellular costs and international roaming.

"Many Russian companies still fully rely on Telegram and WhatsApp messengers for work calls. These [restrictions on calls] once again show how that kind of [dependency] calls into question the total viability of a company," Telecom Daily CEO Denis Kuskov told RBC Life.

Celebrity endorsements

Some of Russia's biggest social media stars have been enlisted to promote Max. Rapper Instasamka — who recently started collaborating with the authorities and even denounces fellow musicians — praised Max's call quality in an Instagram post, claiming she talked for two hours in an underground parking garage without losing connection. Pop star Valya Karnaval, a VK Video ambassador, similarly hailed the app's "perfect connection even while moving or in an elevator."

Musician Yegor Krid went further, plugging Max in his music video for the single "Morye" ("Sea"). Lying in a rubber boat at sea, he tells someone on the phone: "Bro, can you believe it, Max works even at sea!" The hamfisted product placement set off widespread mockery in the comments section.

VK design director Artemy Lebedev pointed to Max's lack of anonymity as its main advantage. In an interview with blogger Amiran Sardarov, Lebedev claimed this feature eliminates bots and spammers. More controversially, he said he appreciated that there were no khokhly (a derogatory slur for Ukrainians) on the platform.

Comedian Denis Dorokhov also joined the campaign, praising the messenger's connectivity while traveling.

Users have mocked the primitive marketing messaging, with streamer JesusAVGN noting that Max is being praised simply for performing its basic function. "With Max, they'll catch you even in the elevator," he joked, hinting that Max, like VK in general, shares data with Russian authorities.

User reviews are highly mixed. "It freezes constantly, and my messages don't always go through," wrote one Google Play reviewer, who rated the app one star. By contrast, an iOS user left a five-star review: "Finally, an app that just works, unlike WhatsApp. Hope they keep improving it."

A state app in all but name

Beyond the glitzy marketing, Max is built to serve a political purpose. Officials want it integrated with the state services portal Gosuslugi via the Unified Identification and Authentication System (ESIA). That would allow citizens to log into government platforms, pay utility bills or sign documents directly through the app, in effect making Max a digital gateway to basic civil services.

But at a government commission meeting in early August, the Federal Security Service (FSB) initially blocked Max's immediate connection to ESIA, citing the risk of personal data leaks. According to IT industry sources cited by Russian media, the FSB submitted a multi-page list of requirements ranging from certified encryption systems to source code audits. Deputy Prime Minister Dmitry Grigorenko, who oversees the project, voiced similar concerns.

By Aug. 7, Digital Development Minister Maksut Shadaev announced that Max had met all FSB security requirements for Gosuslugi integration. VK insists remaining issues are being addressed, though full integration is now expected only by late autumn.

For now, Max looks like any other chat app: no additional features are visible, and the integration of government services is far from clear.

From ministries to apartment blocks

Even without full access to Gosuslugi, state institutions are aggressively pushing the public to adopt Max. Moscow's Housing and Communal Services Ministry has ordered all building and neighborhood chats to migrate from WhatsApp and Telegram to the new messenger. According to former Moscow City Duma deputy Yevgeny Stupin, the edict comes directly from the Construction and Housing Ministry. Posters instructing residents to download Max are appearing in apartment building entrances across major cities, including Moscow and St. Petersburg.

In the republic of Bashkortostan, housing management companies were required to transfer all resident chats by Aug. 25. The State Housing Inspectorate has sent similar directives to management companies in the Moscow, Tula, Nizhny Novgorod, Krasnodar and Belgorod regions, as well as the republic of Bashkortostan, Ostorozhno Novosti reported.

Educational institutions in over 20 regions are also being forced to transition to Max, with the republics of Tatarstan, Mari El and Altai, as well as the Khanty-Mansi autonomous district and the Vladimir and Tver regions, participating in a pilot project to move all school chats there. Tatarstan authorities announced that Education Ministry workers, school and kindergarten principals and staff, students and their parents must all transition to Max by November.

A teacher from Tatarstan told the exiled news website Vyorstka he was "frightened that coercion [from the authorities] will start again."

"They'll probably once again force us to pressure children and parents [to use Max]," the teacher said.

"At work, we were told that soon we will all be required to switch to Max. They didn't specify what exactly that means, or how we'll use it. It's unclear if I can refuse. Knowing that Max is a tool of state control, I would really rather not," a 63-year-old pediatrician in St. Petersburg who asked to remain anonymous told The Moscow Times.

According to Vyorstka, at least 57 regions are forcing public-sector workers and officials to transition to Max, impacting schools, housing services and local governments. St. Petersburg State University claims to be "Russia's first university to begin using the national messenger," while the city's governor declared St. Petersburg the first region to use Max for municipal services.

Technical flaws and privacy risks

Max's rapid expansion has exposed its fragility.

When VK launched a public bug bounty program in July, security researchers uncovered several critical vulnerabilities within weeks. According to VK, it has paid out more than 220,000 rubles ($2,700) in rewards, with the company now offering up to 5 million rubles ($62,000) for discovering serious security flaws — underscoring both the risks of rushed development and the urgency of patching flaws.

Max can only be installed using Russian or Belarusian phone numbers, with virtual SIM cards blocked and registration from other countries impossible. This effectively cuts off Russians abroad from communicating with family and friends in Russia via Max unless they somehow obtain a Russian or Belarusian number.

A recent independent analysis described Max as highly intrusive, noting that it collects IP addresses, geolocation and contact lists, with its privacy policy explicitly stating it may share this data with government bodies and "company partners." The app requests access to a phone's camera, microphone, Bluetooth, notifications and biometrics. Developers also rely on open-source code from foreign countries, including Ukraine — a fact that critics argue undermines Moscow's claims of technological sovereignty.

Security researchers have documented scams targeting Max users, with attackers impersonating technical support and offering "protection activation" services to trick victims into revealing SMS verification codes.

Memes and mockery

Social media has been filled with memes comparing Max to "mandatory Soviet-style queues" and joking that soon "Max will come pre-installed on our kettles and fridges." Others mock the app's glitches, posting screenshots of frozen chats with captions like "sovereign technology in action." On X, one user quipped: "Max works even at sea — but not in my kitchen."

"Public-sector workers in Russia are the most powerless people, on par with migrant laborers. So they’ll carry out any nonsense handed down from above," blogger Anatoly Nesmiyan said.

This humor underscores widespread unease: people may download Max because they are told to, but few appear eager to embrace it voluntarily.

The bigger picture

Max's rise reflects both Russia's digital ambitions and its insecurities. The app is promoted by celebrities and enforced through state decrees, while foreign competitors face growing technical restrictions.

Whether Max becomes a trusted everyday tool or remains a symbol of state coercion will depend on VK's ability to close security gaps, as well as on whether Russians embrace the app as more than just a mandatory download.

Notably, the authorities are not abandoning previous digital initiatives but consolidating them into Max.

Sferum, Russia’s state-run educational platform that combines messaging with online learning tools and has been mandatory in schools since 2022, is being folded into Max. The Education Ministry said Sferum's features will be available within Max starting in the new school year, with pilot regions launching on Aug. 25 and a nationwide rollout by Sept. 15. The Sferum website now directs users to download Max to access its services through the national messenger.

As one teacher from the Vladimir region said of the previous Sferum rollout: "We registered in Sferum when required, but we communicated with other messengers." That pattern could repeat with Max: formal compliance masking continued reliance on foreign platforms — at least while they remain accessible.

The push for Max serves as a critical test of whether Russia can impose digital sovereignty through administrative pressure rather than technological superiority.

With voice calls on WhatsApp and Telegram now blocked, millions of Russians face a stark choice: embrace a messenger they do not trust, or lose convenient communication with friends, family and colleagues.

As the Sept. 1 mandatory pre-installation deadline approaches and more regions enforce the transition, Max may succeed not because Russians want it, but because they have no alternative.

A Message from The Moscow Times:

Dear readers,

We are facing unprecedented challenges. Russia's Prosecutor General's Office has designated The Moscow Times as an "undesirable" organization, criminalizing our work and putting our staff at risk of prosecution. This follows our earlier unjust labeling as a "foreign agent."

These actions are direct attempts to silence independent journalism in Russia. The authorities claim our work "discredits the decisions of the Russian leadership." We see things differently: we strive to provide accurate, unbiased reporting on Russia.

We, the journalists of The Moscow Times, refuse to be silenced. But to continue our work, we need your help.

Your support, no matter how small, makes a world of difference. If you can, please support us monthly starting from just $2. It's quick to set up, and every contribution makes a significant impact.

By supporting The Moscow Times, you're defending open, independent journalism in the face of repression. Thank you for standing with us.

Remind me later.