“Hello! Hello! Mom, can you hear me? You’re freezing up. Let me try calling back without video.”

Over the past couple of weeks, I (and many others) have said these phrases about a minute into almost every call I make home to Russia via Telegram or WhatsApp.

Attempts to block Russia’s most popular messaging apps (WhatsApp is used daily by 67% of Russians, Telegram by 62%) have affected tens of millions of people in Russia and hundreds of thousands abroad, for whom these apps are a lifeline to family and friends.

On audio calls, the words often lag or cut out entirely. Sometimes the connection suddenly improves and you can at least talk in halting bursts; sometimes you can’t hear anything at all.

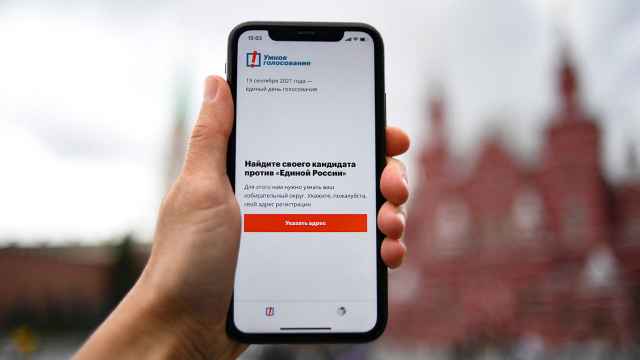

The goal of blocking these apps and replacing them with the Russian-made messenger Max is obvious: total information control, cutting the public off from uncensored news from various current and future “foreign agents,” making it impossible to coordinate protests and gaining full access to users’ messages and interests. The authorities’ official explanation — that the ban is to fight scammers — is best answered with the line from The Godfather: “It insults my intelligence.”

But that claim does not match the facts. According to Kaspersky, in the first quarter of 2025, scammers used mobile phone calls in 43% of cases, not messengers. The Russian Central Bank reports almost the same: scammers accessed sensitive data via mobile calls or SMS in 45% of cases. Only 16% managed through messaging apps.

Roskomnadzor, for some reason, is in no hurry to ban mobile calls. The issue clearly is not exclusive to Telegram or WhatsApp. Scammers have already begun conning gullible users in the brand-new, government-backed Max messenger.

You can still use Telegram and WhatsApp via a VPN — standard or with obfuscation, which masks traffic to look unencrypted — or using the built-in anti-censorship tools already in the apps. But circumventing blocks and Roskomnadzor’s countermeasures is an arms race. Keeping ahead of the authorities is challenging for ordinary people, especially the elderly.

There are many stories where people tried to set up VPNs remotely and teach relatives how to use them, only for them to surrender to Max’s convenience, even though it functions far less reliably than “enemy” counterparts.

Administrative pressure plays a big role. In Putin’s Russia, public-sector workers — long treated like serfs — have no choice over what apps they use. Government agencies, universities, and schools have been ordered to move their work chats to Max. The same demands go out to property management companies, which are told to move building-wide chats into the state’s surveillance messenger.

It may not be long until we see a final block on Telegram and WhatsApp, plus mandatory linking of the new Russian messenger to everything from the state services portal to bank and online store verification codes. This is already being discussed.

If you want to know what that will look like, just look at China’s national messenger WeChat, in place since 2011. More than 90% of the population uses it. It is fully integrated with all possible services and entirely under state control.

Privacy level? Zero. There is no end-to-end encryption; the company that “owns” it, Tencent, can read any messages, personal or group. The system automatically scans for keywords to delete opposition content.

Stories of memes (like comparing autocrat Xi Jinping to Winnie the Pooh) or messages suddenly disappearing from chats are routine in China. Accounts with frequent negative content or criticism of the Chinese Communist Party (which has its own cell inside Tencent) can be monitored and lead to punishment, including criminal charges.

For example, in 2017, Shandong resident Wang Jiangfeng received a one-year and ten-month prison sentence for calling Xi Jinping a “steamed bun” in a group chat. A Chinese court ruled it was defamation and “disrupting public order.” In 2019, journalist Ding Lingjie and two human rights activists were sentenced to 20 months in prison for a video parodying Xi Jinping.

The Russian Max messenger is clearly just as open to the FSB as WeChat is to Chinese state security. Programmers on GitHub published the results of their study of Max, which concluded: “This is not just a messenger — it’s a damn center for total data collection!”

It is easy to imagine the enthusiasm with which Russian security officers will prowl Max’s group chats and private messages to cook up showcase criminal cases. Right now, people are already jailed for “discrediting” the army or spreading “fakes” via social media posts. But soon, the same charges could be applied to group messages in the “sovereign” messenger.

Professional informers will be the only losers — their job will no longer be needed when users’ own devices report them. Send a picture of Navalny or a link to an FBK investigation to a “closed” group of 20 people, and you could be shipped off to serve time. One can only hope that most Russians, saddled with this digital snitch by the state’s “voluntary-compulsory” order, will have the sense not to incriminate themselves this way.

And to ensure that the multiethnic Russian people harbor no doubts about the benevolent intentions behind Makh, State Duma deputy Sergei Boyarsky decided that the pro-government bloggers and bots singing the app’s praises weren’t enough, and proposed checking its most vocal critics for “foreign influence.”

Is Russia becoming a digital gulag? There are two scenarios for how this could play out.

The most optimistic is that authorities fail to block Telegram and WhatsApp. After all, they already tried with Telegram in 2018, and everyone knows how that ended. People keep using them as their main messengers and, if pressured, hide Max on a burner phone with minimal sensitive data.

The more pessimistic (and sadly most likely) outcome is that Max becomes firmly established among the majority and what little social and political activity exists will retreat offline. The tiny fraction of people still able to dodge surveillance via VPNs or alternative messengers (say, Armenian or Arab ones) will face infiltration by provocateurs.

In either case, communication between those abroad and those who remained, as well as among people in Russia, will become much harder. It will not quite amount to a full communications Iron Curtain, since contact will still be possible with effort. But the majority — intimidated and easily drawn into conforming — will be entirely under propaganda’s sway.

For the repressive Russian regime, cutting off war critics and critics of Putin from their families is, of course, a special pleasure.

Last but not least, communication between emigrant journalists and sources inside Russia — which has already grown far more difficult over the past three and a half years — will become impossible or nearly so. Russian society will sink even deeper into apathy and hopelessness.

Even loyal Russians are unlikely to be thrilled at the idea of being under constant FSB surveillance. In Perm, approval for a rally against internet censorship obtained by the political party Rassvet (Dawn) was revoked the same day — apparently because the authorities realized too many discontented people in the million-strong city might show up. No governor or mayor wants to be punished for that.

As for President Vladimir Putin, who professed lover in chief of all things sovereign, he could not care less about who or why is upset. All his Kremlin wants to do is extend its control.

A Message from The Moscow Times:

Dear readers,

We are facing unprecedented challenges. Russia's Prosecutor General's Office has designated The Moscow Times as an "undesirable" organization, criminalizing our work and putting our staff at risk of prosecution. This follows our earlier unjust labeling as a "foreign agent."

These actions are direct attempts to silence independent journalism in Russia. The authorities claim our work "discredits the decisions of the Russian leadership." We see things differently: we strive to provide accurate, unbiased reporting on Russia.

We, the journalists of The Moscow Times, refuse to be silenced. But to continue our work, we need your help.

Your support, no matter how small, makes a world of difference. If you can, please support us monthly starting from just $2. It's quick to set up, and every contribution makes a significant impact.

By supporting The Moscow Times, you're defending open, independent journalism in the face of repression. Thank you for standing with us.

Remind me later.