AMSTERDAM — A tsar, who rose to the throne through the murder of a young heir, is asked to stay in power by an impoverished populace for the sake of their nation’s stability.

Yet haunted by the ghosts of his past, he descends into paranoid madness as a pretender to the throne marches on Moscow.

Modest Mussorgsky’s opera “Boris Godunov,” the story of a late-16th-century boyar who ascended to the top of tsardom during the crisis following Ivan the Terrible’s death, offered a wellspring of material for the exiled director Kirill Serebrennikov to craft a towering allegory of modern Russia for the ages.

Based on Alexander Pushkin’s play of the same name, the opera explores themes that continue to resonate in present-day Russia: the corruption of power, complicity amid widespread injustice, fatalism among the masses, the futility of resisting tyranny, and the nature of life and death itself.

“In Putin’s Russia, people remain speechless out of self-preservation, or swear loyalty to the regime. The state literally buys loyalty, offering the poorest villagers money to go to war and kill neighbors — sums they never imagined before. There is no resistance. Those who protested are now imprisoned or exiled,” Serebrennikov said in an interview ahead of the opera’s premiere in Amsterdam.

“But what’s wrong with people who send loved ones to war for a paycheck? Why do the widows thank the state instead of cursing it? How did we get here — where complaints are about rusty rifles or bad food, not the killing of innocents?” he said.

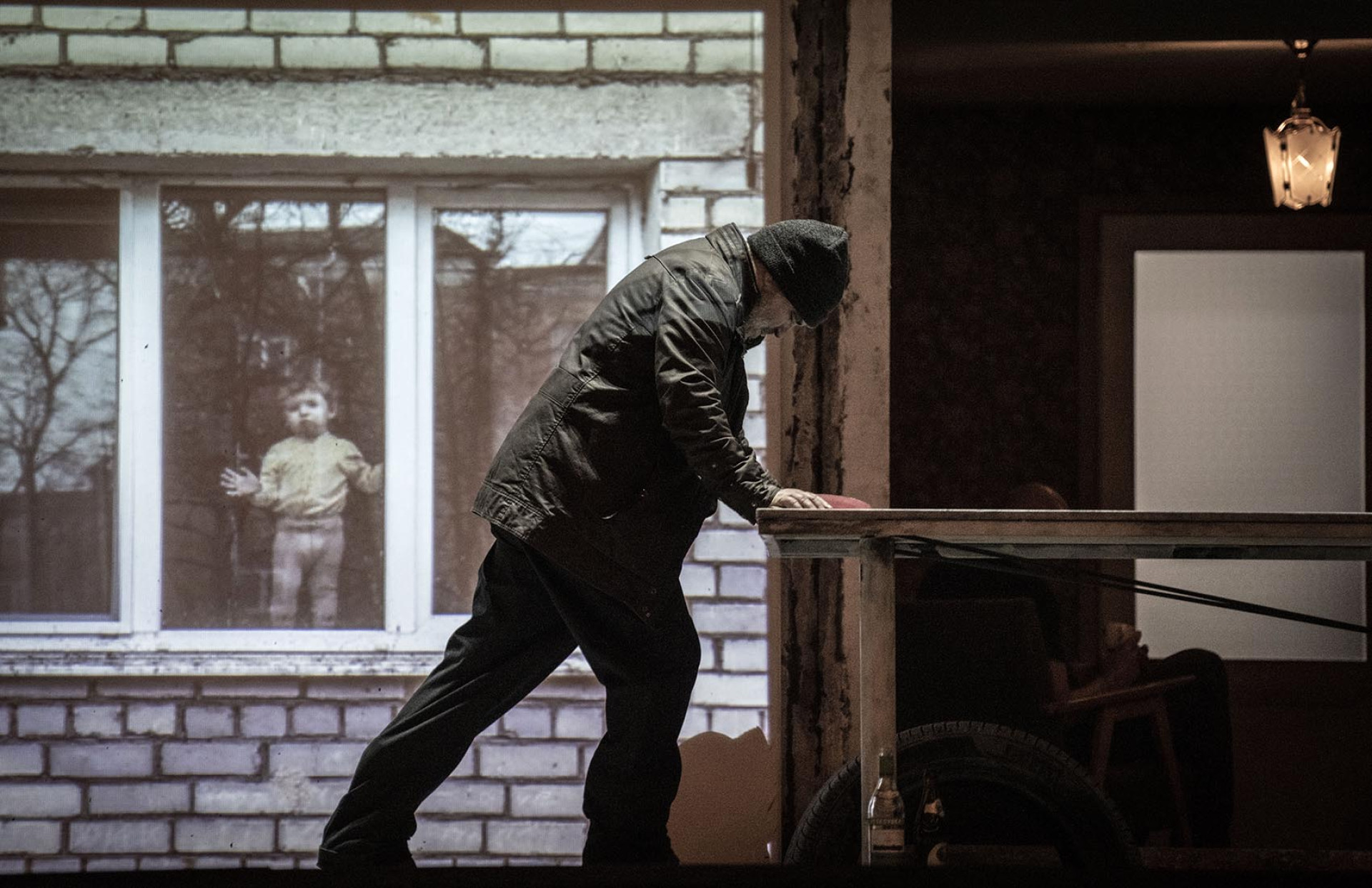

The set design, a grid of prefabricated Soviet-era apartments behind a sparse courtyard, offers a sprawling panopticon of Russian society that indulges the viewer’s gaze with its own side plots away from the main performance.

Anyone who has spent time in Russia will appreciate details like the swans made from car tires often found in residential courtyards, or the street sweepers with their wildly inefficient twig brooms.

Accompanying the set design are photos by the late photographer Dmitry Markov, who died of a drug overdose one day before Alexei Navalny’s death in prison in February 2024.

Like Markov’s photography, Serebrennikov’s production is an unvarnished, unflinching, yet empathetic and unjudgmental depiction of his home country.

The show’s beating heart is The Simple Man, a dissenter who has just served a political jail sentence — and whose fourth-wall-breaking soliloquies are drawn from the final court statements of real political prisoners in Russia.

“Life takes on meaning only when you test fate. I've known that to be true for a long time,” The Simple Man tells the audience. “But what is a person actually to do? The only thing you can do: forget your illusions and be yourself, no matter what. Just like the old prison saying: ‘Don’t fear, don’t believe, don’t hope’.”

In Russian fairytales, the archetype of Ivan the Fool is often the hero of the story, rewarded for his naivete, kindness and simplicity.

But in the bleak world of “Boris Godunov,” there is no lucky twist of fate for people like The Simple Man, who hold on to their conscience and convictions in defiance of the ever-creeping darkness. Nor does the death of the tyrant bring any certainty of a brighter future.

So we beat on, boats against the current, borne back ceaselessly into the past.

“Boris Godunov” is running at the Nationale Opera & Ballet through June 29.

The opera will be live-streamed online on July 13 on Mezzo Live and from July 25 through November 25 on OperaVision.

It will also be screened in Amsterdam on June 22 for Opera in the Park.

A Message from The Moscow Times:

Dear readers,

We are facing unprecedented challenges. Russia's Prosecutor General's Office has designated The Moscow Times as an "undesirable" organization, criminalizing our work and putting our staff at risk of prosecution. This follows our earlier unjust labeling as a "foreign agent."

These actions are direct attempts to silence independent journalism in Russia. The authorities claim our work "discredits the decisions of the Russian leadership." We see things differently: we strive to provide accurate, unbiased reporting on Russia.

We, the journalists of The Moscow Times, refuse to be silenced. But to continue our work, we need your help.

Your support, no matter how small, makes a world of difference. If you can, please support us monthly starting from just $2. It's quick to set up, and every contribution makes a significant impact.

By supporting The Moscow Times, you're defending open, independent journalism in the face of repression. Thank you for standing with us.

Remind me later.