One of the most important events of last year was the exchange of political prisoners in Russia for Western-incarcerated members of the Russian security services. The media wrote extensively about this unprecedented event — the first time since the Cold War when democratic countries rescued Russians opposing the regime and not just their own citizens.

This is true, but if we look at the event not in terms of its symbolism, but in terms of numbers, it is only 16 people — a drop in the ocean of the general situation in Russia. In November, the OVD-info project published a detailed list of oppositionists facing criminal charges. According to the data, almost 1,500 people are already in prison, and many more are awaiting trial. This article is dedicated to all these people.

Since contributors to this article, poets and translators, also run the risk of being accused of terrorism and extremism, no names will be used. In their monologues, as in their poems, they describe Russian everyday life and the repression that is now part of that life. But each poet processes the situation in their own way.

The first poet feels everything as deeply as possible. They have a multi-layered relationship with fear and write in the first person. In this text life appears as a series of crimes; in this space it is impossible to breathe without breaking the law.

The second poem describes casual chatter about prison in a cosmetics store. The lyrical heroine Asya Akatova just plays the role of an observer eavesdropping on someone's telephone conversation. The poet describes daily reality as an attempt to balance on the edge of risk and safety.

The third author is as detached as possible. Their poem is not about a specific situation or any particular person. They observe all that happens from historical perspective and a broader view. The poet says that they live life while trying to avoid thinking about the possibility of going to prison.

я фальсифицирую

я воспрепятствую

я дискредитирую

я пропагандирую

я распространяю

я злоупотребляю

я отказываюсь

я финансирую

я приобретаю

я употребляю

я содействую

я надругаюсь

я принуждаю

я изготовляю

я покушаюсь

я разглашаю

я оскорбляю

я уклоняюсь

я организую

я превышаю

я совершаю

я призываю

я причиняю

я разжигаю

я вовлекаю

я нарушаю

я укрываю

я одобряю

я угрожаю

я отрицаю

я склоняю

я посягаю

я умираю

* * *

i disseminate

i repudiate

i discredit

i influence

i distribute

i organize

i reach out

i threaten

i disclose

i bankroll

i encroach

i infringe

i produce

i approve

i execute

i support

i involve

i shelter

i violate

i misuse

i coerce

i obtain

i kindle

i resist

i insult

i avoid

i abuse

i plead

i apply

i bring

i deny

i fake

i die

It came into my head just before I fell asleep — that’s the way I usually write. I have to be exhausted, in the space between sleep and waking, so that I can meet my subconscious fears. The lines of poems come, I get up, go to the kitchen, smoke and write notes on my phone. I think it was Iggy Pop who said that thousands of brilliant lines were lost because someone had them at night but was too lazy to get up. I try to write more, but usually when I turn on the light, that's it. So a few key moments come in the night like that, and then you turn it over in your mind and finish the next day.

“I die” at the end came right away — it was clear that the text had to end that way. It doesn’t mean that I was killed. It’s that I was born, went to school, and so on, that is, like in “Fight Club” — but about modern Russian life. “Discredit” also came quickly. Now the word is used a lot because of the new section in the criminal code about “discrediting the RF army.” Before the war, the word was rarely used outside academic circles; you could only find it in some monographs in a context like “the industrial revolution has been discredited.” Now the state appropriates language, annexes words so that it’s hard to continue to use them independently in a different cultural context.

Another word that came to me was “distribute”— now you hear it all the time — it’s in the part of the Criminal Code about distributing narcotics. I went through the Criminal Code digging words out so that I wouldn’t forget what else was there. I wanted to collect as many words as possible.

The words in the text are arranged conceptually according to their length. The final one is the shortest, and from the beginning to the end the words thin out and disappear. I wanted this visual transition to be barely discernible, for the reduction of words to be seamless, and for it to be visual poetry.

Most of all I am afraid of becoming a person who is always afraid. Some of my acquaintances and friends are going mad with fear. They are afraid to go outside, to talk to anyone, to use the internet. Of course, we have to take into account the extraordinary situation we are in, but fear should not be the starting point for everything in life. We need to put it away, to fight it.

At the beginning of the war, I read Viktor Frankl's memoirs about the concentration camp he was in. There is his famous line that the first to perish were those who thought it would soon end, the second were those who thought it would never end, and the only ones who survived were the ones who continued to live each day, accepting reality as it was. That’s what I try to do. In my circle of friends this is one of the most important topics, but lately I've gotten tired of discussing it. I don't think it's bad or abnormal if you meet someone, sit in a cafe, drink coffee for three hours and never once talk about the war. You can’t talk about it every day. I was at a protest once, eight years ago. I don't participate in collective actions, I don't want to feel like I’m part of a crowd under any circumstances; I feel physically ill in a place where individuality is lost. And unfortunately, we can’t expect the situation to be changed from the bottom up. It’s already clear that this is impossible and that state pressure is only increasing. My protest is what I write.

I haven't “disseminated” any false information, but I’m sure I’ve “discredited” something and “disclosed” something else. I’ve probably “supported” some negative rumors, “approved” some things I shouldn’t have, and I certainly have not “died”... I haven't “avoided” the draft yet. I’m of draft age and that means something, but for now I have a deferment since I'm studying. If anything, my plan is to do a Kharms. There is a legend that he said something like “I will surrender on the first day. If you need a soldier like me, you can have me.” They put him in a mental hospital where he died, so it didn't save him in the end. But I'm not going to get involved in this war. I'd rather go to prison. I think there's a better chance of survival there.

Ultimately these are very depressing thoughts, but Frankl helped me with that, too. If they come after me or put me in a paddy wagon or something like that, I really don't want my tongue to go numb with horror and be all “I can't sleep, I can't eat.” In this sense I really like the way Ilya Yashin behaves, although in general I’m not a big fan. But throughout all these trials he was psychologically stable and always spoke as a mature person coping with the challenges of the external environment. Navalny was different. Yes, he was always smiling, but I thought he was very tense. But Yashin has always behaved with restraint, and you had the sense that he was the same when the camera was off. He wasn’t falling apart. I would like to behave like that.

Of course, torture is more frightening, and the fear of it is invincible. I once was certain that this was unthinkable these days, but it turned out to be thinkable. It was after the Mayakovsky Readings case, when three poets were tortured — that this was now our reality. I was shocked. The violence and humiliation over just words — I didn’t think it was possible — and so openly — to torture someone in Moscow, to force them to apologize... I pray that all this isn’t systemic and institutionalized, because if it is, it’s the end of the last remnants of civilized society.

Asya Akatova

Подружка

в розовом магазине подружка выбирала карандаши для глаз и говорила по телефону. больше молчала, чем говорила, но иногда говорила.

так и чё. так и посадили его или нет? а дело-то завели? как это посадили но не завели.

выбрала чёрный.

Girlfriend

in the pink “girlfriend” shop she chooses eye liners and talks on the phone. she’s silent more than she talks, but sometimes she talks.

so whatsup? is he in jail or what? did they charge him with something? what do you mean, jailed without a charge?

She chose black.

When the war started, I had to go on a business trip for a month. It was a nightmarish week, because my sister had gone to a protest rally and had been put in jail, and a very close friend had a mental breakdown — he was suicidal, so I stayed with him for a couple of nights. I was also bringing care packages to my sister. I was really afraid that she would be beaten up or raped. At the time I had no idea how violent these men were, and I was drawing conclusions based on what I knew of the Belarusian protests in 2020. I had to leave in a few days, and I had a lot of work to do and packing… I almost didn’t sleep for several days, so I don’t remember them well. But they were the worst days of my life. It took me almost a year to recover. And then on top of it all many people dear to me (including my sister) left the country soon after. I felt abandoned, I felt that I’d been left alone in a hard, cruel world.

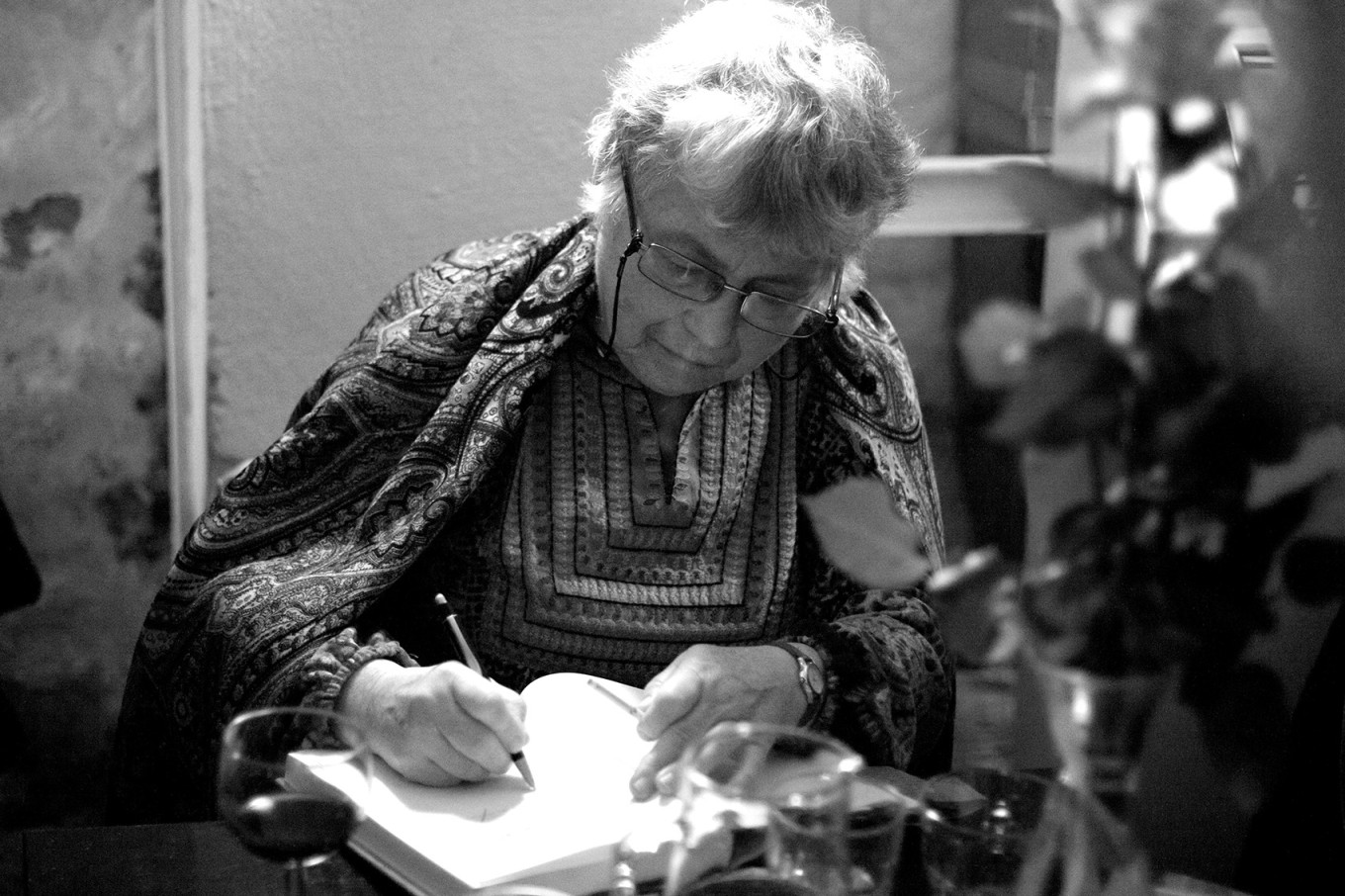

When I came out of my depression, my creativity boomed. I finally switched on the world around me. More than a year had passed since the war started. Emotions had settled down a bit. The crazy panic and confusion was over. It was a period of stagnation, detachment, getting used to it. This is inevitable. My text is about how terrifying and serious things like someone's incarceration become as mundane as choosing eye liner.

I wrote it very simply. I went to the store “Girlfriend” to buy something like tampons or mascara; there was a girl in line next to me talking on the phone. I just remembered two of her phrases. I don't do this on purpose. I really don’t like to eavesdrop, but I just happened to jot down what I heard. And then I sent it to the ROAR (the Resistance and Opposition Arts Review) website along with another text that I liked better. But they chose this one.

I included the name of the store because everyone who's been there knows how bright it is — ultra-girly, Barbie pink. In this beautiful, doll-like, delicate setting, a sweet girl is picking out cosmetics and discussing things like this... Pink is contrasted with black. It may be banal, but that's the contrast that got me. She spoke completely calmly, mentioning the fact of incarceration in passing... She said something else, but I only remembered those two lines.

We don't know what social stratum this girl is from, what her circumstances are. Maybe half of her classmates are in jail for petit larceny or for selling hash. If this had happened a few years ago before the war, I probably wouldn’t have first thought it was a political arrest — she didn't say what that person had been imprisoned for. But at that time literally every day someone was imprisoned for oppositional views, and I was immediately certain that’s what had happened. Besides, there was a nuance — the girl says he was “jailed without being charged.” The processing of political cases is typically absurd. The accusation is often made up without any evidence. And the procedures and rights of suspects and defendants are violated.

I think a lot about art under censorship; how anyone could write or make a film in those conditions; how people survived in similar situations in different countries and different eras. It's definitely better to write than not to write, better to do than not to do, and even in a situation of strict censorship you can express yourself creatively... I'm not interested in entering into discussions with people who think that artists who do something under censorship are somehow guilty for the war. It’s ridiculous to hold them responsible; we are hostages to this situation. My personal responsibility is to not support the state, to not say what I don't believe in.

I publish my works in ROAR under a pseudonym and I would not read these texts publicly anywhere. I am afraid of being charged with discrediting the army or something like that, although there is nothing like that in the texts. The censorship is opaque, obscure and random. Arraignments and sentences are illogical and have nothing to do with the meaning of what is written. I don't want to play this lottery. I'm extremely cautious in general. I don't show my face anywhere. I don’t protest or use my name to make any public statements. I immediately realized that it was very dangerous and that in my case it was not worth it. I am not a journalist or an activist; that’s not my path. And I think that I would not survive the arrest, that my psyche would not withstand such a dehumanizing experience.

My sister was only in jail for five days, but to me it felt like a really long time. I'm very close to her, and I think she's fragile and delicate. She does things because “I had to do something…” I never imagined that she would be treated like that. To be fair, according to her it was relatively okay. She said, “I just lay there and read the books you brought me.” She was in jail with some very nice people, girls like her who went to the protest — a philosophy student and a journalist, something like that. But it was in a very unpleasant and unhygienic place — she hardly ate a thing the whole time she was there, and when she came out she was pale and miserable, but she said she was fine.”

Это укоренившееся заблуждение

что слэм изобретён в Америке

или где-то-там ещё

слэм конечно придумали

изначально в России

только в Российской версии слэма

судьи – это реальные судьи

и поэт за стихи

получает не баллы

а сроки

(по-тюремному если – «срока»)

Мандельштам

Хармс

Введенский

Олейников

Заболоцкий

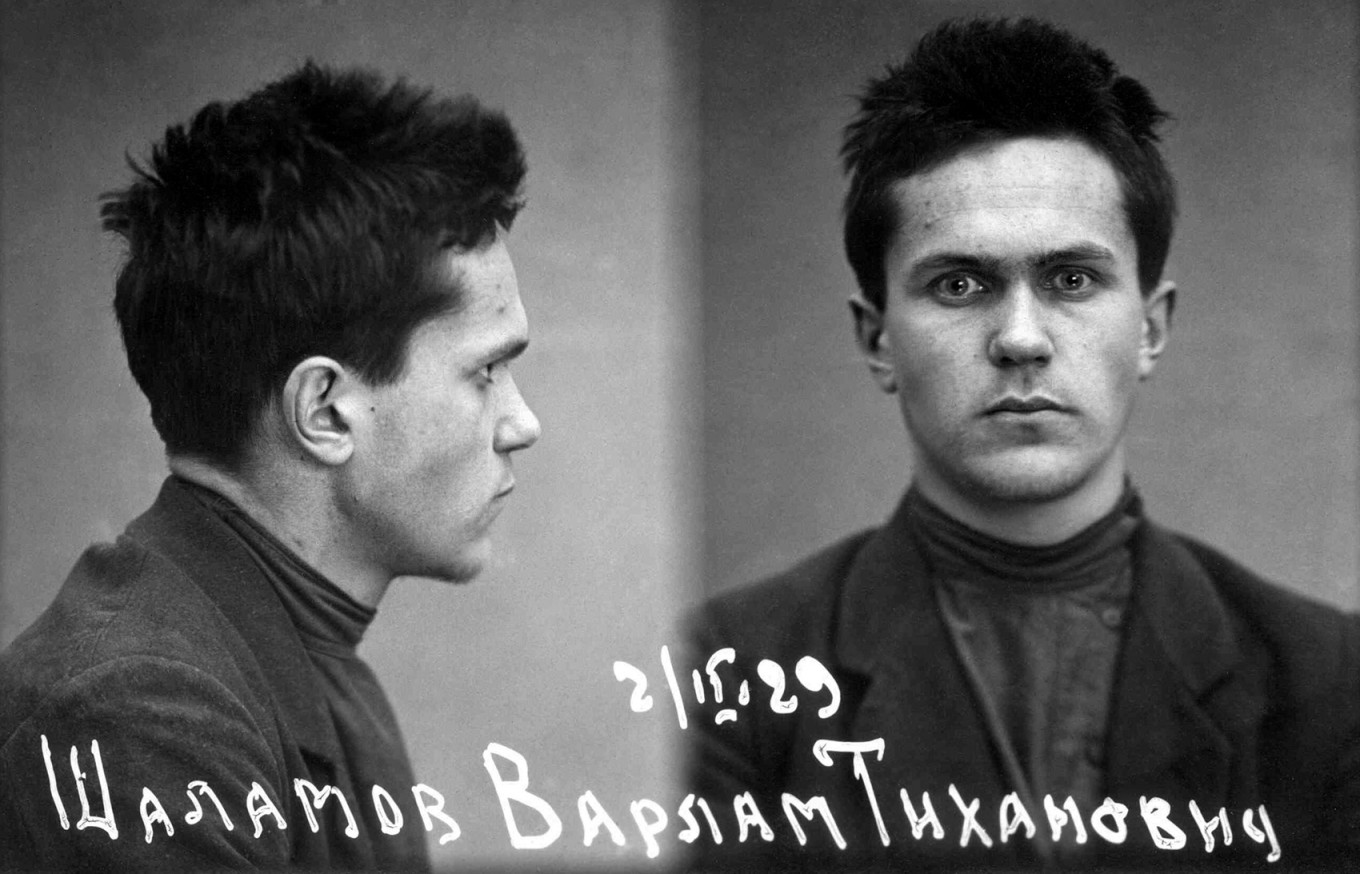

Шаламов

Домбровский

Есенин-Вольпин

Чертков

Делоне

Горбаневская

Бродский

…

это только общеизвестные

а сколько их было на самом деле?

сколько будет ещё?

русский слэм продолжается и продолжается

Александра Скочиленко

Артём Комардин

Егор Штовба

Евгения Беркович

Слава Малахов

* * *

There’s a deep-seated misconception

that slam poetry was invented in America

or somewhere else

but of course slam

was invented in Russia

only in the Russian version of slam

judges are real judges

and for the poetry a poet

doesn’t get points

he gets a jail term

(in prison talk it’s “doing time”)

Mandelstam

Kharms

Vvedensky

Oleynikov

Zabolotsky

Shalamov

Dombrovsky

Esenin-Volpin

Chertkov

Delaunay

Gorbanevskaya

Brodsky

...

these are just the ones we know

how many have there really been?

how many more will there be?

Russian slam goes on and on

Alexandra Skochilenko

Artyom Komardin

Egor Shtovba

Yevgenia Berkovich

Slava Malakhov

It was after the final slam — 2023 when all those detentions happened — Petriychuk and Berkovich, the Mayakovsky case — and the slam was kind of sleepy. There were some great people there, but it was as if they were ashamed to perform powerfully. It was unclear how to continue without making the tragedy worse. Later we could talk about the same things as before, but with a bit more energy and inspiration. But at the time we couldn’t. It was like there was a kind of internal seesaw tossing you up and down even though the circumstances were the same. We were depressed. On our way back, we went into a courtyard. It was New Year's Eve, and there was a Christmas tree all lit up, a house on one side and the prison wall on the other with a playground right next to it, completely empty... The next day or a couple of days later, I wrote this poem.

The idea of short performances on the border between rap and poetry somewhere in a bar, where you are judged by the bar’s visitors, originated, of course, in America, somewhere in the 1980s and 1990s. And then it spread. In Russia slam appeared thanks to the writer Vyacheslav Kuritsyn, who in 2001 organized one in Moscow and St. Petersburg. Since then slam has changed a lot. Slams have been held in different places and in very different ways. I joined in 2006. I didn't know anything about slams then. Instead of three minutes I read for almost six minutes. I didn’t sense how long I was speaking because a spoken text isn’t the same as a text written on paper, and I had a lecturer’s habit of speaking slowly and clearly. But now I'm already kind of a veteran. I've won five times and once went to an international championship in Paris.

Slams are probably not really a natural part of the Russian cultural tradition. I think it appears in a city just because there’s someone to organize it. Historically, we have had some elements of slam, like when Igor Severyanin was elected king of the poets. That was something similar, perhaps an echo of the influence of the Italian Futurists, a desire to transplant something unusual to our environment.

The beginning of the poem, about slam being invented in Russia, is a bit ironic. It brings to mind an anecdote about how Stalin ordered his minions to find analogs to all world's great inventions in the USSR.

“They come to Stalin and say, ‘We found everything, and Russians invented the radio and the steam engine, but the only thing we didn’t find was the blow job. They say the French invented the blow job.’ Stalin demands that they find proof that the blow job was also invented in Russia. So they dig through the archives and bring a letter from Ivan the Terrible to the boyars where he says ‘I f*ck you all in the mouth and see right through you!’ So the Russians invented X-rays, too!”

But since I wrote the beginning of the poem knowing what would come next, it’s a kind of pseudo-irony. I understand almost literally that slam has existed in our country in the insidious way I describe. But there was no word for the process: a person reads a text, but then it’s not a drunken judge or a customer to a bar giving him points, but a real court deciding on a sentence. There is a process, but there is no word for it. Why not call it Russian slam?

In the poem I listed only poets I remembered off the top of my head who were jailed for their poetry. I put these names in roughly chronological order, as I remembered, and then I didn't change anything. They created quite a rhythm.

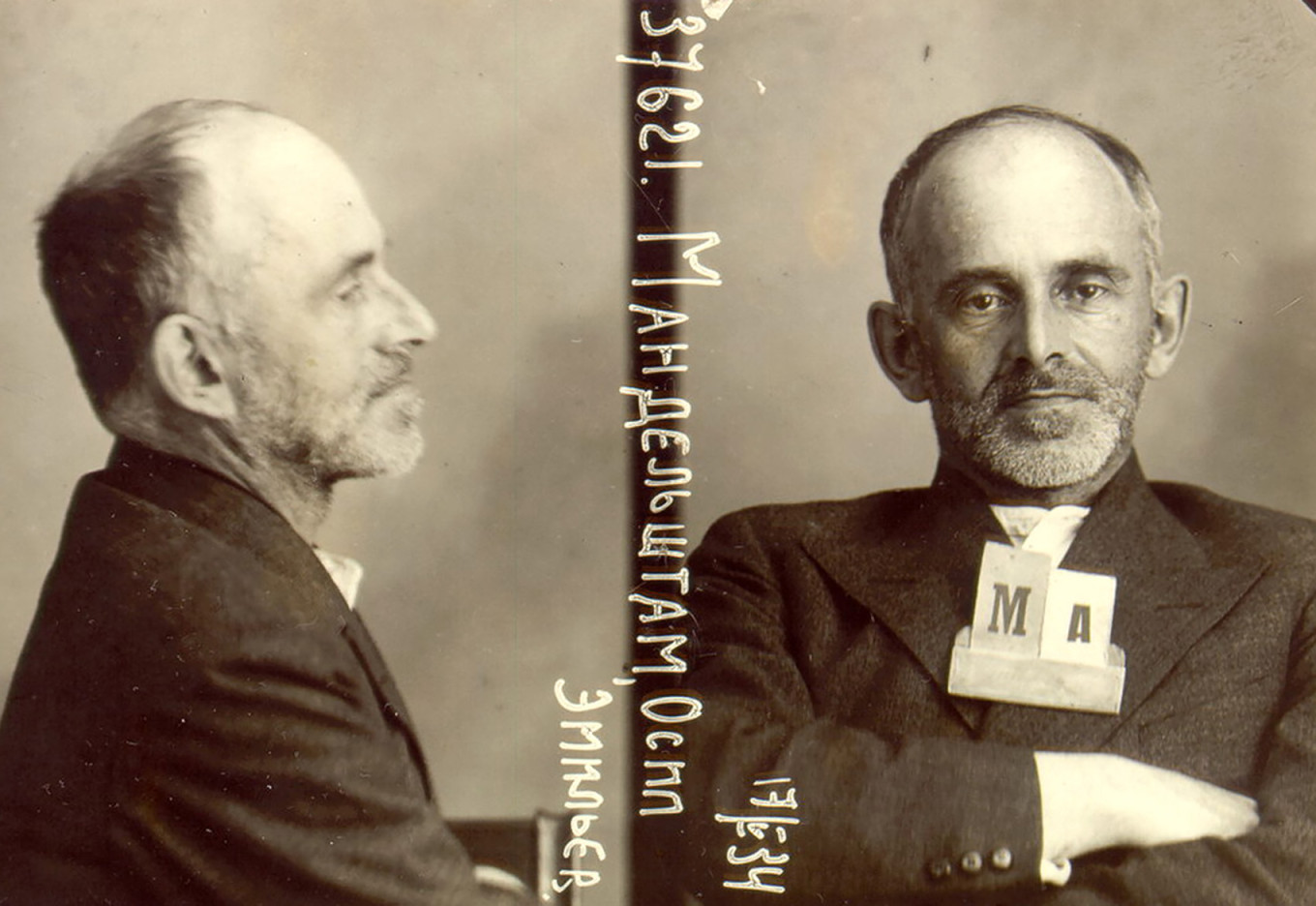

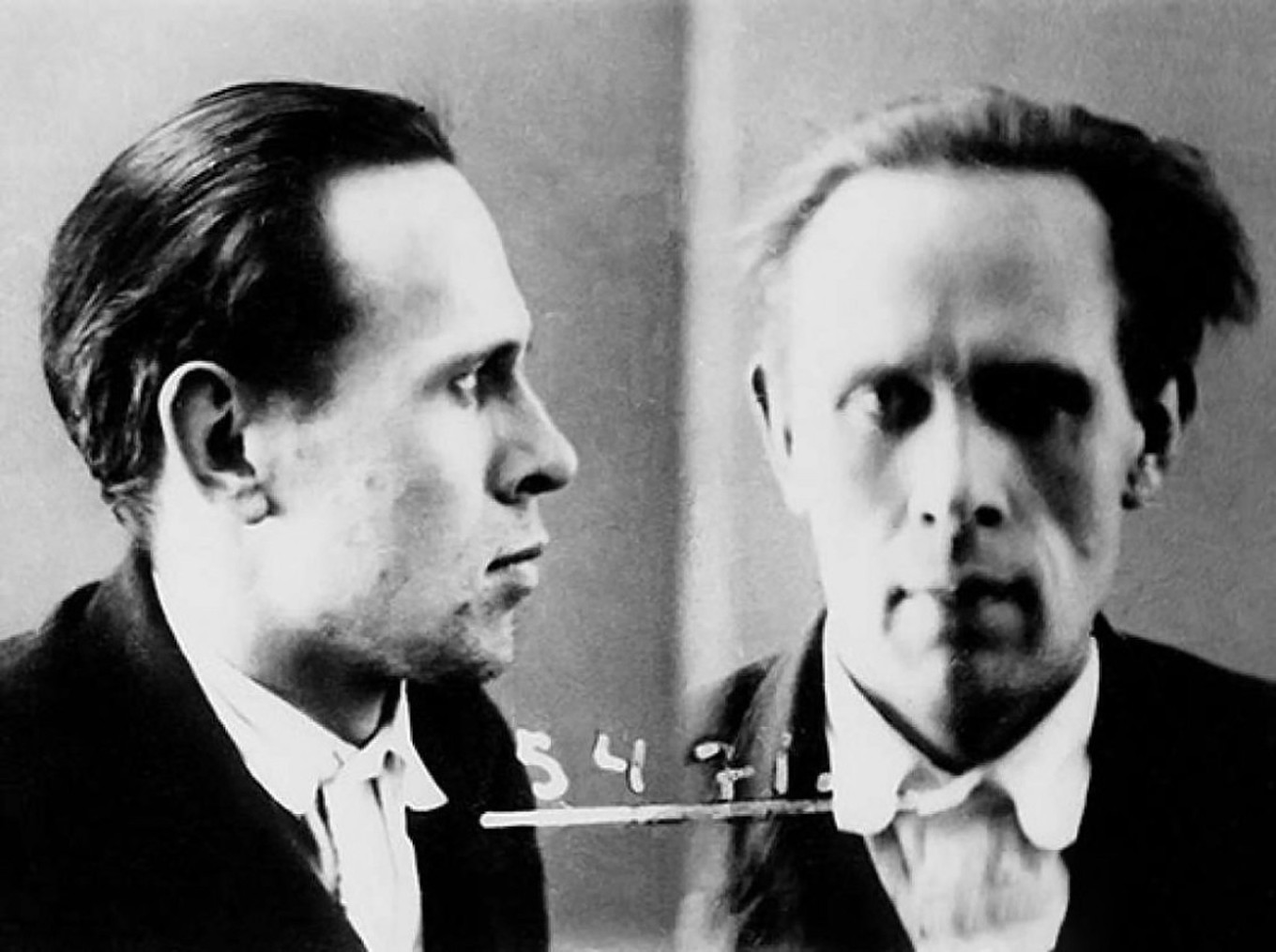

Osip Mandelstam was arrested for an epigram against Stalin and exiled to Cherdyn, then arrested again a few years later and died in a transit camp. In the 1930s Daniil Kharms, Alexander Vvedensky, Nikolai Oleinikov, Nikolai Zabolotsky — poets of the OBERIU group — fell into the system’s meat grinder. Oleinikov was shot, Vvedensky died in transit, Kharms starved to death in a prison psychiatric clinic. By some miracle, Zabolotsky survived. After the camps and exile he returned home and was even published. In one of the prefaces to a collection of Zabolotsky's poems, it is evasively written that from 1938 to 1945, Zabolotsky's literary activity was “interrupted.”

Varlam Shalamov spent more than fifteen years in the camps. Yury Dombrovsky wrote works where the most valuable thing is the feeling of desperate freedom in the last frontier. Alexander Esenin-Volpin was author of the memo “How to behave at interrogations.” Leonid Chertkov organized a home poetry club and was sentenced to five years in the post-Stalin era. Vadim Delaunay and Natalya Gorbanevskaya took part in the demonstration against Soviet troops entering Czechoslovakia. I even managed to see Gorbanevskaya when she came to Russia in 2010. And Brodsky, everyone knows about Joseph Brodsky — not only about his poems, but also about the “trial of the slacker Brodsky”.

And then modern poets… I put Activist Alexandra Skochilenko — who was released in the prisoner exchange — among the poets, because what she was imprisoned for was, in fact, the poetry of direct action. The others are still in jail. I know Slava Malakhov personally.

Since 2022, of course a feeling of the underground and a little bit of danger has appeared, although all my compositions are character-based — I transform into some other being and try not to feel my own feelings as much as possible. I am an introverted person, I rarely talk about anything in public, my voice is soft. I don’t discuss anything about this with students. Sometimes they’ll come up to me and ask me how I feel about things, and then I might say something. Sometimes I have to take censorship into account [at performances] so as not to get the organizers in trouble, but in general I don't think [about the possibility of arrest] at all. My brain hides my fears from me.

It's like with children. Their psyche protects them. They run along the edge of cliff and don’t even think for a second that they might run the wrong way and fall. That protects them because if you start to imagine it, then you’ll definitely run off the cliff. I think this is our general state. There is a general feeling of false security because if you don’t have it, it’s difficult to do anything... When you have some illness and have to go to work, your body suppresses it. The illness develops inside, but outwardly everything is normal while you’re at work. Then you come home and immediately get sick and die.

A Message from The Moscow Times:

Dear readers,

We are facing unprecedented challenges. Russia's Prosecutor General's Office has designated The Moscow Times as an "undesirable" organization, criminalizing our work and putting our staff at risk of prosecution. This follows our earlier unjust labeling as a "foreign agent."

These actions are direct attempts to silence independent journalism in Russia. The authorities claim our work "discredits the decisions of the Russian leadership." We see things differently: we strive to provide accurate, unbiased reporting on Russia.

We, the journalists of The Moscow Times, refuse to be silenced. But to continue our work, we need your help.

Your support, no matter how small, makes a world of difference. If you can, please support us monthly starting from just $2. It's quick to set up, and every contribution makes a significant impact.

By supporting The Moscow Times, you're defending open, independent journalism in the face of repression. Thank you for standing with us.

Remind me later.