Ilya Yashin, the Russian opposition politician sentenced to eight-and-a-half years in jail by a Moscow court last week for speaking out against the Russian army’s civilian massacre in Bucha, is a familiar face in Russian politics but remains little known internationally. What can his two decades in politics tell us about the state of the opposition in Russia?

Born into Moscow’s liberal intelligentsia in 1983, Yashin began his political career in 2000 when he joined Yabloko, a liberal party then represented in the Duma, and the only major faction to have opposed the Second Chechen War. He describes himself as "a normal, European, left-wing liberal." He is a liberal in the Russian sense: he wants to see his country become a constitutional democracy modeled on European values where the rule of law is respected.

While Yabloko’s repeated electoral defeats took their toll on the party’s old guard, it provided young, energetic activists such as Yashin with much-needed motivation. He quickly rose through the party’s ranks, organizing new forms of protest better adapted to the conditions in which Russian elections were fought.

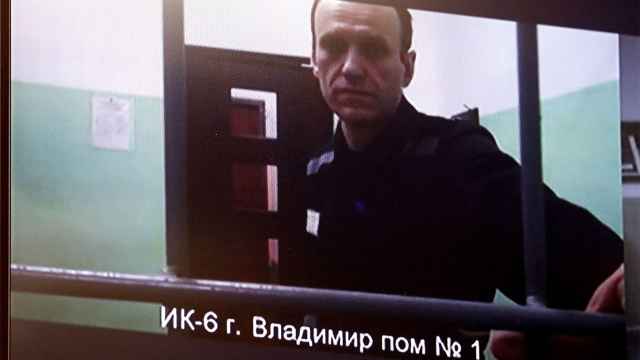

Comparisons between Yashin and Alexei Navalny, a fellow Yabloko member with whom he shared an office at one time, are inevitable. Though Yashin was never a member of Navalny’s organizations, the two men built a lasting friendship and alliance. So much that Navalny described Yashin as his “first friend in politics” in a statement of support issued from his own penal colony on learning of Yashin’s long sentence.

Confident, ambitious, and determined, both men were, in the words of political scientist Tatyana Shukan, “imbued with the cultural capital and charisma that makes a political leader” and represented a new generation of opposition politicians seeking to replace an old guard that seemed forever doomed to failure.

Yet there are significant differences between the two men as well. While Navalny is known for being brash and quick-tempered, Yashin is more mild-mannered and polished, and unlike Navalny in his earlier years in politics, had no interest in fusing nationalism and liberalism.

Even at that time, Yashin believed that trading freedom for security was a ticking time bomb, and these fears proved to be remarkably prescient as the political opposition in Russia was slowly dismantled and Yashin himself was forced to make the transition from oppositionist to dissident.

Ukraine’s Orange Revolution in late 2004 made a strong impression on Yashin who traveled to see the Maidan in Kyiv and later became the informal leader of Oborona, an unregistered youth group for liberal activists inspired by the success of a wave of “color revolutions” across the former Soviet Union. Oborona sought to take the fight against authoritarianism to the street, breaking with routinized forms of protest by organizing provocative performances and flash mobs instead. By this time, Yashin was already what his friend Alexis Prokopiev calls “a European-style politician,” someone who in France or Germany “would have been a member of parliament or a minister.”

In 2008, he co-founded Solidarnost, a movement seeking the Holy Grail of Russian liberalism: a way of uniting its warring factions, which succeeded in winning the support of Boris Nemtsov, then one of Russia’s most prominent opposition leaders. However, Yashin’s extra-curricular activities led to his expulsion from Yabloko, though he has subsequently claimed that the real reason was his criticism of Grigory Yavlinsky, the party’s domineering veteran leader.

Now a close friend and associate of Nemtsov, Yashin joined his political mentor in the liberal People's Freedom Party (PARNAS), and following Nemtsov’s assassination in 2015, helped complete his final project: a report on the war in eastern Ukraine, which had begun the previous year, concluding that “attempting to stop the war is true patriotism.”

In 2011, Solidarnost organized a rally in Moscow to protest against fraud in the recent legislative elections. The event was an unexpected success, kickstarting what came to be known as the For Free Elections movement, the most important protest cycle during Putin’s rule to date.

Already a talented and fluent speaker, Yashin gained a more prominent platform from the For Free Elections movement and was among the opposition activists who refused to leave Pushkin Square on the day after Putin’s return to the presidency was announced.

Like many other Russian opposition figures, Yashin was repeatedly denied the chance to hold any real political power as the system ensured that all his attempts to win political office ended in failure. In 2017, as repression in Russia continued to grow, Yashin set his sights on a far more modest goal — that of becoming a municipal deputy in Moscow’s Krasnoselsky district in order to gain “experience in real government.”

Yashin swept through the district and duly became the local council leader and was soon eyeing a run for the Moscow Duma. It turned out that his election in 2017 would be a one-off event, however, as most opposition candidates were disqualified from running in these elections.

The invasion of Ukraine on Feb. 24 heralded the end of any electoral hope for Yashin within Putin’s system, however. As soon as wartime censorship was adopted in March, Yashin knew the authorities would be coming for him.

Yashin’s final words in court were unwavering: “Do what you must, come what may. When the hostilities began, I did not doubt what I should do even for a second. I must remain in Russia, I must speak the truth loudly.”

It's obviously too soon to say how spending years of his life in prison — the fate of so many dissidents — might affect Yashin, but the trajectory of his uncompromising career from party member, street activist, and local politician to a prison camp tells the tragic story of Russia’s liberal opposition in the 21st century.

A version of this article originally appeared in German in Dekoder.

A Message from The Moscow Times:

Dear readers,

We are facing unprecedented challenges. Russia's Prosecutor General's Office has designated The Moscow Times as an "undesirable" organization, criminalizing our work and putting our staff at risk of prosecution. This follows our earlier unjust labeling as a "foreign agent."

These actions are direct attempts to silence independent journalism in Russia. The authorities claim our work "discredits the decisions of the Russian leadership." We see things differently: we strive to provide accurate, unbiased reporting on Russia.

We, the journalists of The Moscow Times, refuse to be silenced. But to continue our work, we need your help.

Your support, no matter how small, makes a world of difference. If you can, please support us monthly starting from just $2. It's quick to set up, and every contribution makes a significant impact.

By supporting The Moscow Times, you're defending open, independent journalism in the face of repression. Thank you for standing with us.

Remind me later.