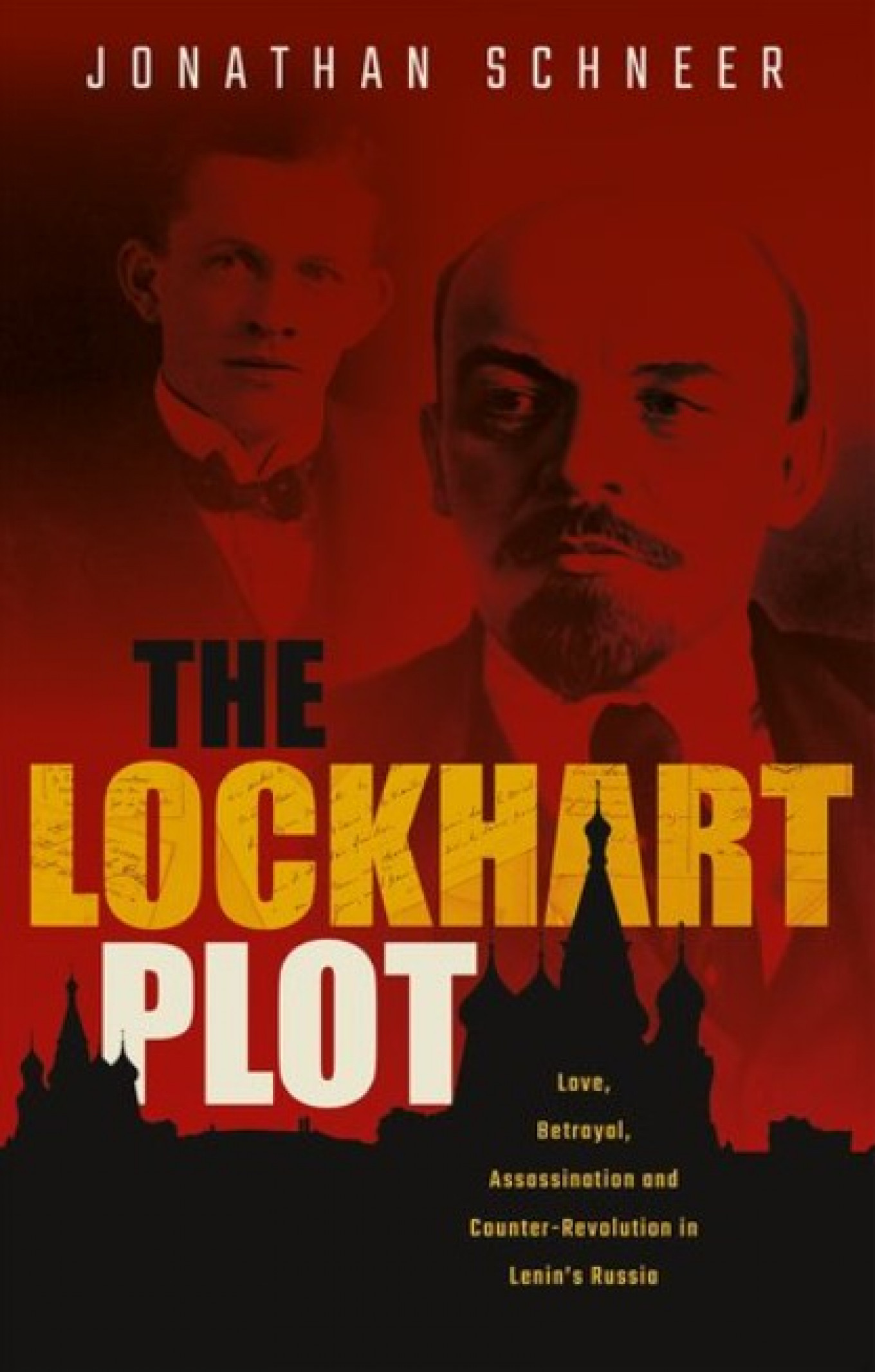

“It is like something in a novel,” wrote Vladimir Lenin of the original Lockhart plot — an ill-starred Anglo-French plot to overthrow the Bolshevik government in the summer of 1918. He may as well have been talking about Jonathan Schneer’s new book of the same name, a thoroughly researched, vividly novelistic account of politics, romance and espionage in the early days of post-revolutionary Russia.

The Oxford University Press watermark should not deceive. Though clearly of historical interest, “The Lockhart Plot” reads, at times, rather more like a riveting, old-school spy novel than an academic treatment of an unfairly neglected historical episode.

The (capital P) plot goes something like this: Shortly after the October Revolution, Bruce Lockhart, a multilingual Scottish gentleman diplomat and philanderer is ordered back to Russia by prime minister David Lloyd George, only months after having been sent home as punishment for a romantic misadventure with a suspected Bolshevik militant.

With newly established Soviet Russia teetering on the brink of destruction amid internal subversion, German aggression and the embryonic White Army, Lockhart is tasked with somehow getting Russia back into the war. Initially sympathetic to the Bolshevik cause, he ends up roped into a half-baked plot to overthrow Lenin’s government by suborning the Latvian riflemen who then comprised the core of the Red Guards.

The conspiracy’s discovery by the Bolshevik Cheka secret police — who allow the plotters to incriminate themselves and the capitalist West — ends our story with the death of some of our protagonists, and with most of the rest expelled from Russia.

Aided and abetted by his lover Moura Beckendorff, a renegade Ukrainian countess, and “Sidney Reilly,” a mysterious, Russian-born freelance spy who served as an inspiration for Ian Flemming’s James Bond, the unflattering comparisons to the airport spy thriller might write themselves, were it not all true.

And yet the book is so much more than that. In the book’s epilogue, Schneer describes “The Lockhart Plot” as “a story of love and romance and idealism — and of their curdling.” It is indeed all of these things. Helped along by Schneer’s colorful, free-flowing prose, we are given a remarkable study in the corruption of idealism against the roiling background of a revolutionary Russia lurching towards the Red Terror.

Lockhart, the Russophile initially convinced of the need to find an accommodation with the Bolsheviks, finds himself improvising a madcap plot to depose Lenin with orders to that effect, largely because he imagines that it might please his superiors. Even the implacable secret policeman Felix Dzerzhinsky, only one of the book’s astonishingly rich stock of historical cameos, is rendered in a deeply human — almost sympathetic — portrait of a man willing to go to abhorrent ends to protect and defend his life’s work.

Amid the book’s high drama emotional rollercoasters, it’s easy to forget what it offers to historians: an object lesson in how, at a crucial turning point in Russian history, Western policy to the new-born Soviet state was determined in no small part by a cast of characters seemingly plucked from the pages of a “Flashman” novel. That alone should recommend this extraordinary little book.

Excerpt from Chapter One of "The Lockhart Plot"

The Making of Bruce Lockhart

January 11, 1918: a gray and somber day in London during the fourth year of a war that had devastated half the world and whose outcome no one could yet predict. Two Russians representing the Bolshevik regime that had taken power in Russia the previous October, and two Britons representing the government of their own country, sat across from one another at a table in the Lyons Corner House in the Strand near Trafalgar Square. In such modest and incongruous settings the world may be shaped, or undone. The quartet had just finished lunch. Now, in a room barely lit by a few weak bulbs, and by the feeble, slanting rays of an overcast northern winter sky, one of the Russians was writing a letter in Cyrillic characters. He used the table at which they had just dined as his desk. When he finished, his companion quickly provided an English translation. The letter was addressed to “Citizen Trotsky, People’s Commissariat for Foreign Affairs,” and the first paragraph read:

Dear Comrade, – The bearer of this, Mr. Lockhart, is going to Russia with an official mission with the exact character of which I am not acquainted. I know him personally as a thoroughly honest man who understands our position and sympathizes with us. I should consider his sojourn in Russia useful from the point of view of our interests.

While the two Britons nodded their satisfaction, the author of the letter ordered a French dessert—“pouding diplomate” (diplomat pudding)—but the waiter returned a few moments later to say there was none left. This was a poor augury for the “official mission” referred to in the letter, yet, when the meal concluded and the four men departed the restaurant, at least one of them disappeared down Whitehall into the darkening afternoon with a spring in his step. Maxim Litvinov had been denied his “pouding diplomate,” but as usual, young Bruce Lockhart, whom the British government was about to send to Moscow to parlay with Lenin and Trotsky, had gotten just what he wanted. This time, it was a reference letter from the only person in England who could smooth his way with the Bolshevik government in Russia. Of course, he had no inkling that also he had set into motion a train of events that would culminate in the audacious plot that bears his name.

* * *

In 1918, Bruce Lockhart was 31 years of age. He stood, according to his passport, five-foot seven inches tall (the average height of a British soldier at that date was about five-foot five). He had blue eyes, brown hair above a high forehead, ordinary nose, medium mouth, and square face. He had jug ears and a stocky frame. He stares coolly from the century-old passport photo with an assessing, slightly skeptical, self-assured and intelligent gaze.

It is a true and revealing photograph, the impression it makes only reinforced by a description of Lockhart’s speaking voice provided later by one of his friends: “assertive and modest, arrogant and humorously depreciative at the same time.”

He was born in 1887 in Anstruther, Fife, Scotland, and proudly claimed to have no drop of English blood in his veins. He had spent his childhood in the bosom of a large, happy, close-knit and prosperous family. His mother’s side owned an old established distillery, Balmenach, at Cromdale near Grantown-on-Spey; his father’s side held extensive interests in the rubber plantations of Malaysia. His parents sent young Lockhart to the exclusive Fettes College in Edinburgh, where he distinguished himself not as a scholar but as an athlete. In fact, he inherited outstanding athletic ability. It gave him self-confidence—perhaps too much.

Upon leaving Fettes he did not go to Cambridge as his father had done, and where sports might again have distracted him, but rather to the “Institute Tilley” in Berlin, where he learned German and, finally, “how to work,” and then to Paris where private tutors took him in hand. The results were gratifying: the teenager who loved sports now found that he could pick up languages easily (he would claim to “speak some six or seven” only a few years later), displayed a wonderful memory, and discovered a passion for literature, poetry, theater, and art that never left him. Soon he could recite by heart passages from Heine in the original German, and the works of the aesthete and travel writer Pierre Loti in the original French.

In 1908 he returned to England to prepare for the Indian Civil Service exam. He buckled down to study for a serious test; he knew now that he could compete with the best students; a real career beckoned. Then one of the rubber plantation uncles visited the family and excited the young man’s imagination with tales of the romantic, mysterious Orient. Lockhart impulsively dropped his books and sailed east with his relative.

He was 21 years old, impetuous but formidable. He learned the Malay language as he had learned French and German, with ease. “He has exceptional abilities,” wrote his first employer in Malaya. Recognizing them, his uncle sent him to open up a new rubber estate near Pantei, in Nigeri Sembilan. The young man made a success of this too. But along with high intelligence, natural authority, and acute perception, he would soon display a dangerous streak of recklessness.

Early in 1910, he gave a party. His gaze fell upon the most beautiful girl he had ever seen, “a radiant vision of brown loveliness.” Her name was Amai, and he knew that he must have her. That she was about to marry into the highest reaches of local society did not deter him; perhaps the challenge excited him. His campaign of seduction nearly amounted to stalking, but he won her. Characteristically, he did not consider what might come after; and if he thought about the sacrifices Amai would have to make—and then did make—to be with him, they did not weigh heavily on his mind. Everyone opposed the match, including some who might take deadly measures to end it. After a period of months characterized by bliss with her and strife with practically everyone else, Lockhart fell desperately ill, probably with malaria, but possibly from poison. His suffering was intense, but he was too proud to seek professional help. Eventually Amai summoned a doctor who prescribed immediate flight, not directly to Lockhart, but on the young man’s behalf to his uncle. The next day this gentleman and a cousin bundled the weakened young Scot into an automobile and conveyed him to the ship that would provide the first leg of his journey home. Lockhart later claimed that he had protested—but could his relatives have overborne him if he truly had been determined to stay?

The elegiac tone of a 1936 memoir suggests that on one level he always regretted the end to this affair. But also it had been a narrow escape, for the life of a colonial planter never could have satisfied him, which he surely knew. At any rate, here was a pattern that would recur: more than once in the years to come, Lockhart would ignore convention and his own better instincts while pursuing an attractive young woman; would experience initial success and delight; but then would face the disapproval of powerful figures whom he dared not oppose, and to whom, after some heartburning, he would yield. The affair with Amai was a harbinger.

Back in Scotland, momentarily chastened, this time he agreed to take the Consular Service exam. He listed as referees the managers of the Malayan plantations on which he had worked, confident they would overlook his amorous misadventure. They did. “At all times honest, sober and well conducted,” wrote one of them. “I have the highest opinion of his character and capacity,” wrote the other. From his former headmaster he obtained the following testimonial: “R. H. B. Lockhart was educated at Fettes College. He had considerable intellectual capacity and was very prominent in games. I recommended his Father to endeavour to find him a career in the Consular Office, in which I think his abilities should make him very serviceable.” With this endorsement in his pocket, Lockhart headed for London to cram for the exam. This time he really did buckle down, which meant that no one could beat him. When the grades were made public his name appeared at the top of the list. He had come first in every category.

And reaped the reward. His first posting was a plum: vice consul in Moscow. A week before his departure his parents threw a farewell party in his honor. There he spied another vision of loveliness, this time of the Australian variety. Her name was Jean Adelaide Haslewood Turner. As with Amai, he knew immediately what he wanted, and did not think beyond. He had only seven days to gain his objective, but again he mounted an irresistible whirlwind campaign. In this instance no powerful forces intervened, and the pair would marry the first time he came home on leave a year later. But it would not be a happy marriage.

Excerpted from “The Lockhart Plot: Love, Betrayal, Assassination and Counter-Revolution in Lenin’s Russia,” by Jonathan Schneer, published by Oxford University Press. © Jonathan Schneer 2020. Used by permission. All rights reserved. Footnotes have been removed to ease reading. For more information about Jonathan Schneer and his book, see his publisher’s site here.

“The Lockhart Plot” has been shortlisted for the 2021 Pushkin House Book Prize.

A Message from The Moscow Times:

Dear readers,

We are facing unprecedented challenges. Russia's Prosecutor General's Office has designated The Moscow Times as an "undesirable" organization, criminalizing our work and putting our staff at risk of prosecution. This follows our earlier unjust labeling as a "foreign agent."

These actions are direct attempts to silence independent journalism in Russia. The authorities claim our work "discredits the decisions of the Russian leadership." We see things differently: we strive to provide accurate, unbiased reporting on Russia.

We, the journalists of The Moscow Times, refuse to be silenced. But to continue our work, we need your help.

Your support, no matter how small, makes a world of difference. If you can, please support us monthly starting from just $2. It's quick to set up, and every contribution makes a significant impact.

By supporting The Moscow Times, you're defending open, independent journalism in the face of repression. Thank you for standing with us.

Remind me later.