The exhibition of painter Robert Falk (1886-1958) in the New Tretyakov Gallery begins with a comment about the leader of the U.S.S.R. “Nikita Khrushchev was not prepared for this kind of painting,” it reads.

The painting in question was “Nude in an Armchair.” In 1962 the First Secretary of the Central Committee of the Communist Party, Nikita Khrushchev, called it “perverted.” It was being shown at an exhibition dedicated to the 30th anniversary of the Moscow Union of Artists. “For the present this kind of creativity is considered indecent,” said Khrushchev, whose taste leaned more to red banners and official portraits.

In the Soviet Union Falk’s “Nude” was reproduced only in black and white, which turned it into an unappealing muddle. The public called it “Naked Valka,” a derogatory play on the “Nude of Falk.”

Today when you finally see the original painting, it's instantly clear that it is a masterpiece. Falk painted it in the cold and hungry winter of 1922-23 at VKHUTEMAS, the art institute founded in the first years after the Revolution and then dismantled in the 1930s when socialist realism became the only approved artistic style.

Art historians like to tell stories about Falk’s model, the famous Stanislava Osipovich, who posed for many famous Russian painters and sculptors. She was drawn by Valentin Serov, carved in marble by Sergei Konenkov and Lev Kerbel. In the first years after the Revolution when artists’ studios were filled with little puffs of frozen breath and the artists worked in fur coats, warming their hands over coal braziers, Osipovich stood nude, motionless, frozen blue, and as stiff as iron. Artists wrote in their memoirs that she agreed to pose nude at any temperature.

There is a legend that she posed for Falk next to a stove, which explains why her side closer to the heat “got roasted” while the other side was blue from the cold. Falk used his unique color scheme of warm and cold paints, unerringly choosing the palette mastered in the studios of his French artist friends: deep dark red, brown, gold.

Specialists also see the influence of cubism on Falk in that period. The show displays another painting called the “Crimean Nude” (1916). Its palette echoes the colors of the painting that so disturbed Khrushchev, but this one seems to burst out of the frame that can't contain the grand forms within. Art historians call this the “force of powerful form typical of the Jack of Diamonds,” a group of painters in the early 20th century which included Falk, Pyotr Konchalovsky, Alexander Kuprin, and Ilya Mashkov.

The exhibition of works by Robert Falk is the first show in Russia to fully present his oeuvre. On display are 200 works: paintings and graphics, from portraits to sketches for theatrical sets. As Alexei Mokrousov noted in his fine review in Novaya Gazeta, “people have waited for the show a long time, for 60 years, so we shouldn’t be surprised at its success...”

To France and back

In his early career Falk, like all the other Russian avant-garde painters, went through a period of impressionism. The portrait of Lyala Falk — the artist’s cousin — is reminiscent of Renoir and other French portrait painters. In 1928 Falk went to France for a period that his biographers consider the most mysterious and difficult to understand in his artistic biography, where he painted a gray, bland, sunless world in muted colors.

At the end of 1937 Falk returned to the Soviet Union. In France he’d missed the extraordinary changes taking place at home: Russian art had been shackled; authorities battled against formalism and invented socialist realism; instituted this new policy and identified dissidents, who expressed deep regret. His long absence from the Soviet context protected him and let him live the life he wanted to live, not the one imposed on him. That’s why he was able to preserve the style that irritated Khrushchev so much.

With the help of his influential friends, Falk was issued a studio in the famous Pertsov House on Prechistenskaya naberezhnaya, where all Moscow came to see art unlike the works on display in Soviet museums: works by the Wanderers, even works by the founders of the Stalinist style, such as Pavel Sokolov-Skal (whose studio Falk miraculously inherited) or Fyodor Reshetnikov (“Another ‘D’), Alexander Laktionov (“Letter From the Front”) or Yuri Neprintsev (“Rest After the Battle,” Mao Zedong’s favorite painting).

Falk was an iconic figure in post-Stalinist Moscow during the second half of the 1950s. The writers Veniamin Kaverin and Ilya Ehrenburg, who coined the use of “the thaw” to describe the early Khrushchev years, made literary characters based on him.

The two posthumous exhibitions of Falk’s work held in the Soviet Union in 1958 and 1966 were hugely popular and confirmed that the public wanted to see something that wasn’t so “soviet.”

Portraits, landscapes, and interiors

The exhibition has many interesting portraits: of poet Ksenia Nekrasova, writer and literary critic Viktor Shklovsky, and Solomon Mikhoels, the brilliant actor and director assassinated by Stalin’s henchmen. The portraits of Falk’s wives are particularly fine. In each portrait, male or female, Falk reveals himself to be not only a master of color but a subtle psychologist. An excellent example is the portrait of Midkhat Refatov, a Crimean-Tartar writer who translated Tolstoy’s “War and Peace” into Turkish and was executed by the White Army in Crimea in 1920.

Another very fine portrait is of the artist Alexander Drevin. Done in 1923, it is held by the Sepherot Foundation in Liechtenstein. Drevin is downcast, and it almost seems that Falk foresaw the tragic fate awaiting his subject, who was executed in the Polish-Latvian Campaign of the NKVD in 1938.

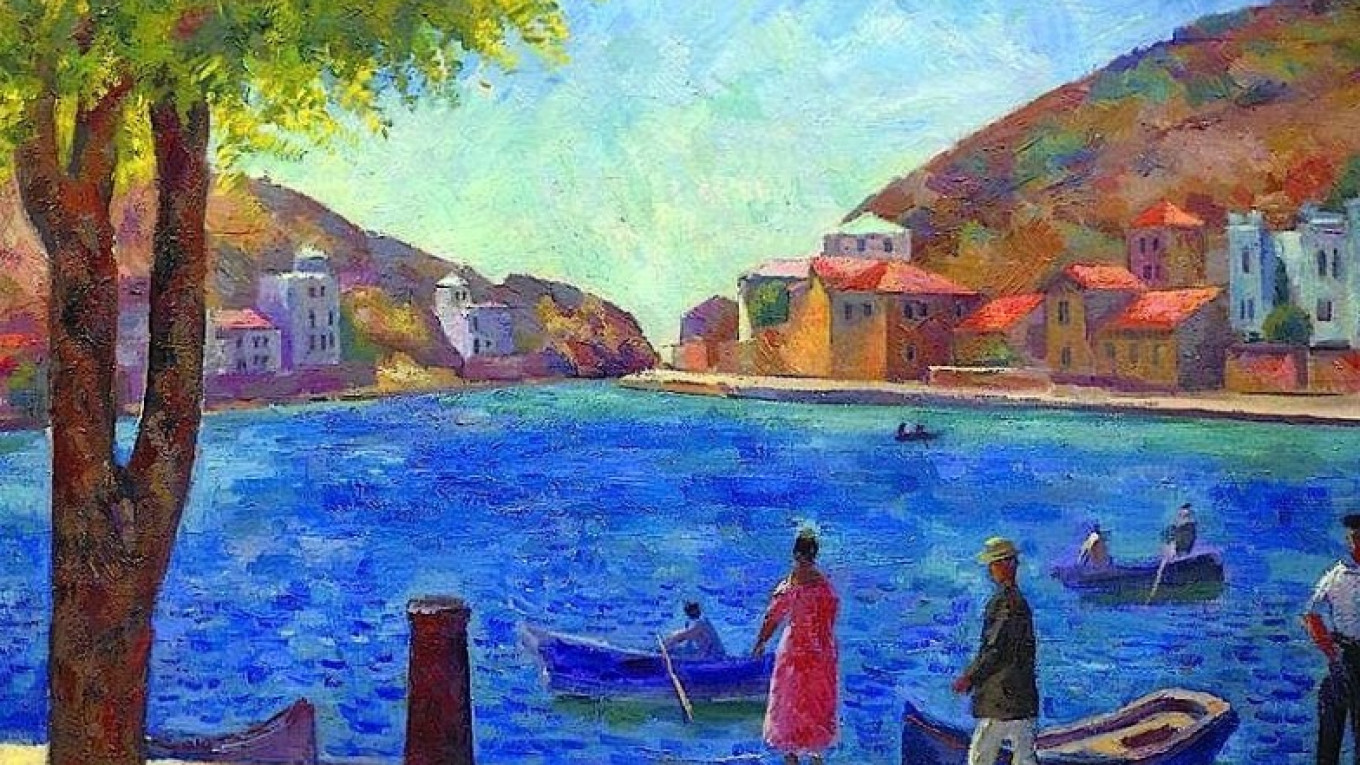

Falk also painted many landscapes of Crimea, including the fine “Bay in Balaklava.” Falk’s mastery of color is on center stage here: he brilliantly captures the complex blue color of the Black Sea.

Of course, the exhibition also includes the famous painting “Red Furniture,” a still-life/interior that has enthralled viewers with its complex color palette. The painting has been reproduced many times and is part of the Tretyakov’s permanent collection, but presented here in the context of all of Falk’s works, it makes a particularly powerful impression. The variegated red upholstered furniture hang, as it were, on the stretch white tablecloth, giving the painting a sense of wholeness and space. “Red Furniture” has such magnetism that even the most inveterate anti-formalists stand before it, transfixed.

Over time, toward the end of his life, Falk’s works seem to grow duller, as if he’d used up all the tubes of paint he’d brought back from Paris. Soviet strictures began to repress him, and he was no longer capable of innovative experiments.

But in this exhibition, we can finally see the entire arc of his creativity.

The exhibition runs until May 23. For more information about the show, see the site here.

A Message from The Moscow Times:

Dear readers,

We are facing unprecedented challenges. Russia's Prosecutor General's Office has designated The Moscow Times as an "undesirable" organization, criminalizing our work and putting our staff at risk of prosecution. This follows our earlier unjust labeling as a "foreign agent."

These actions are direct attempts to silence independent journalism in Russia. The authorities claim our work "discredits the decisions of the Russian leadership." We see things differently: we strive to provide accurate, unbiased reporting on Russia.

We, the journalists of The Moscow Times, refuse to be silenced. But to continue our work, we need your help.

Your support, no matter how small, makes a world of difference. If you can, please support us monthly starting from just $2. It's quick to set up, and every contribution makes a significant impact.

By supporting The Moscow Times, you're defending open, independent journalism in the face of repression. Thank you for standing with us.

Remind me later.