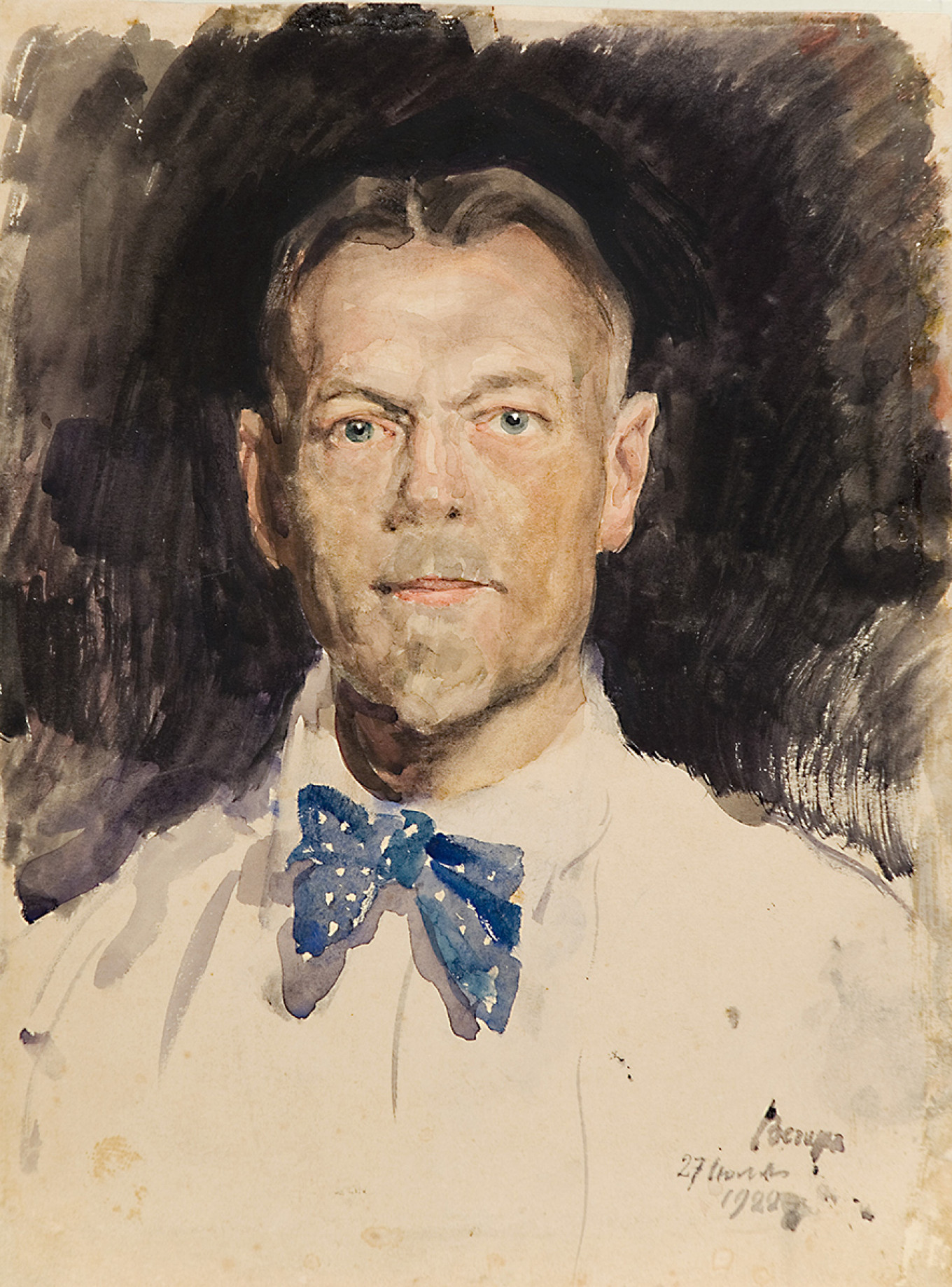

This fall the Museum of Russian Impressionism opened an exhibition called “Sergei Vinogradov: A Painted Life,” about a brilliant artist who worked in the late 19th and early 20th centuries and yet is almost unknown today. The exhibition is a voyage of discovery, introducing the public to works by a painter of the same caliber as Isaak Levitan, Valentin Serov, and Konstantin Korovin. As an émigré, he was unfairly forgotten and removed from the context of Soviet and Russian art for many decades.

A remarkable eye for art

Vinogradov was born on June 7 (19 New Style), 1869 in a large family of a rural priest in a village in what is now Yaroslavl oblast. From 1880 to 1889 he studied at the Moscow School of Arts, Sculpture and Architecture under the artists Konstantin Makovsky and Vasily Polenov, who introduced him to Isaak Levitan. In the spring of 1901, he went to Paris where he discovered the paintings of old masters in the Louvre, visited the studio of August Renoir and became acquainted with Claude Monet.

To a very great degree, the works of the great foreign artists of the turn of the century appeared in Russian thanks to the taste, breadth of knowledge, and intuition of Sergei Vinogradov. It was Vinogradov who convinced Mikhail and Ivan Morozov to begin collecting Western art and later curated their collection that included works by Paul Cezanne, August Renoir, Claude Monet, Edgar Degas, Vincent Van Gogh and many others. Many of those works that were first recognized as brilliant by Vinogradov are now in Russia’s finest state museums.

Vinogradov later recalled a buying trip with Mikhail Morozov:

“When Misha and I were buying works by Renoir, in Ambroise Vollard’s gallery we saw the first few paintings by Paul Gaugin that had just arrived from Tahiti, where Gaugin lived like a local Tahitian. The works were very interesting in terms of color, but they were so unusual, done with such primitive forms that it took quite a bit of courage to purchase one of those canvases at that time. But all the same, once I got over my first strange and astonished impressions, I sensed that this was real art, and significant art. I tried to convince Mikhail Morozov to buy one painting that was particularly marvelous in its colors. The works cost almost nothing. Misha began to hoot with laughter and said no. Then I decided to buy the painting myself. With that Misha caved in and bought it for 500 francs.”

On Oct. 29, 1912, Vinogradov was given the honorary title of Academician of the Imperial Academy of Arts. In 1916, he was elected an acting member of the Imperial Academy.

Vinogradov spent the last years of his life in Latvia and was buried in Riga.

Today Russian art lovers can see images from the distant past, from a world that has disappeared forever: manor houses lit by the sun; actresses and dancers such as Karolina Otero (1868-1965), who thrilled Belle Epoque audiences. Her portrait from the Museum of Fine Arts in Karelia opens the exhibition.

A world captured on canvas

Music sung by Fyodor Chaliapin, Vinogradov’s fishing partner, and Anastasiya Vyaltseva, a celebrated mezzo soprano of the time, plays in the background of the show. The curators note that Vinogradov refused to accept the revolutionary changes going on around him and continued to pay homage to the patriarchal world of the empire, both rich and poor.

The show displays images of simple peasants who look as if they might have been the models for the illustrations in Richard Pipes’ book “Russia Under the Old Regime.” Here they all are: hermits, pilgrims, and beggars.

This world is especially vibrant in a section of the exhibition called “Manor House Life 1907-1910,” which has paintings of interiors and facades of country estates. Vinogradov spent a great deal of time in Golovinka, which belonged to Vsevolod Mamontov, the younger son of Savva Mamontov. Vinogradov also captured on canvas the interior of the house owned by artist Konstantin Korovin near the village of Ratukhino by the river Nerl. Korovin, a great lover of hunting and fishing, bought the property from Savva Mamontov and then designed and built a wooden house and studio there.

But the most memorable works at the exhibition are his intoxicating, sun-filled Crimean landscapes. Vinogradov spent the summer months of 1915-1917 in Crimea — that is, the two years before the October Revolution when his world would collapse. At the time Crimea was the vacation spot of Nicholas II and other Russian noble families. The artist adored Crimean vistas, which he often painted with lovely women, deep in thought, staring into the distance of the Black Sea. The poster for the exhibition has a painting with this kind of pre-Revolutionary beauty in a panama hat. Her head is turned to the right so her face isn’t visible, and viewers can image their own version of this beautiful stranger. On the table before her lie peaches covered by a deep blue shadow that exists only in Crimea.

There are several paintings of the famous mountain of Crimea: “View of Ai-Petri,” loaned by the Kovalenko Art Museum in Krasnodar, and “Alupka. Crimea. 1917” from the State Museum of the Republic of Tatarstan. This painting depicts Ai-Petri, cypresses, and a local couple, frozen in a serious conversation. His paintings of this period have something in common with the works of Konstantin Korovin, whom Vinogradov often visited in the Crimean town of Gurzuf.

Crimea was where Vinogradov fell in love, where he courted his student, 15 years younger than him — Irina Voitsekhovskaya. She became his muse and closest friend. They married in 1918 and lived together until Vinogradov’s death. Voitsekhovskaya then moved to Canada and died in Montreal in 1953.

Below see a performance and tour of the exhibition (in Russian.)

In 1923 Vinogradov was one of the organizers of a major exhibition of Russian art in the U.S. The show, which opened on March 8, 1924 in the Grand Central Palace, displayed more than 1,000 works done by about 100 of Russia’s best artists. It was a great success. But Vinogradov used the chance to leave the Soviet Union with the paintings, and he never returned. He settled in Latvia and worked in Latgale with his students.

“There he worked a great deal, wrote, taught, traveled and missed his homeland. He published lengthy texts about the his life in Moscow that he loved so much, and he died in 1938, on the eve of tumultuous events that were even more enormous than what he’d already experienced,” curator Yulia Petrova noted.

This exhibition of works by Sergei Vinogradov is a prime example of the museum’s charter to explore, discover and rediscover Russian impressionism. The curators have introduced art lovers and visitors to Sergei Vinogradov, one of the founders of Russian impressionism, in all his variety and complexity.

For more information about the exhibition and online events, see the museum site.

Below see a lecture in Russian about Sergei Vinogradov with a tour of the exhibition.

A Message from The Moscow Times:

Dear readers,

We are facing unprecedented challenges. Russia's Prosecutor General's Office has designated The Moscow Times as an "undesirable" organization, criminalizing our work and putting our staff at risk of prosecution. This follows our earlier unjust labeling as a "foreign agent."

These actions are direct attempts to silence independent journalism in Russia. The authorities claim our work "discredits the decisions of the Russian leadership." We see things differently: we strive to provide accurate, unbiased reporting on Russia.

We, the journalists of The Moscow Times, refuse to be silenced. But to continue our work, we need your help.

Your support, no matter how small, makes a world of difference. If you can, please support us monthly starting from just $2. It's quick to set up, and every contribution makes a significant impact.

By supporting The Moscow Times, you're defending open, independent journalism in the face of repression. Thank you for standing with us.

Remind me later.