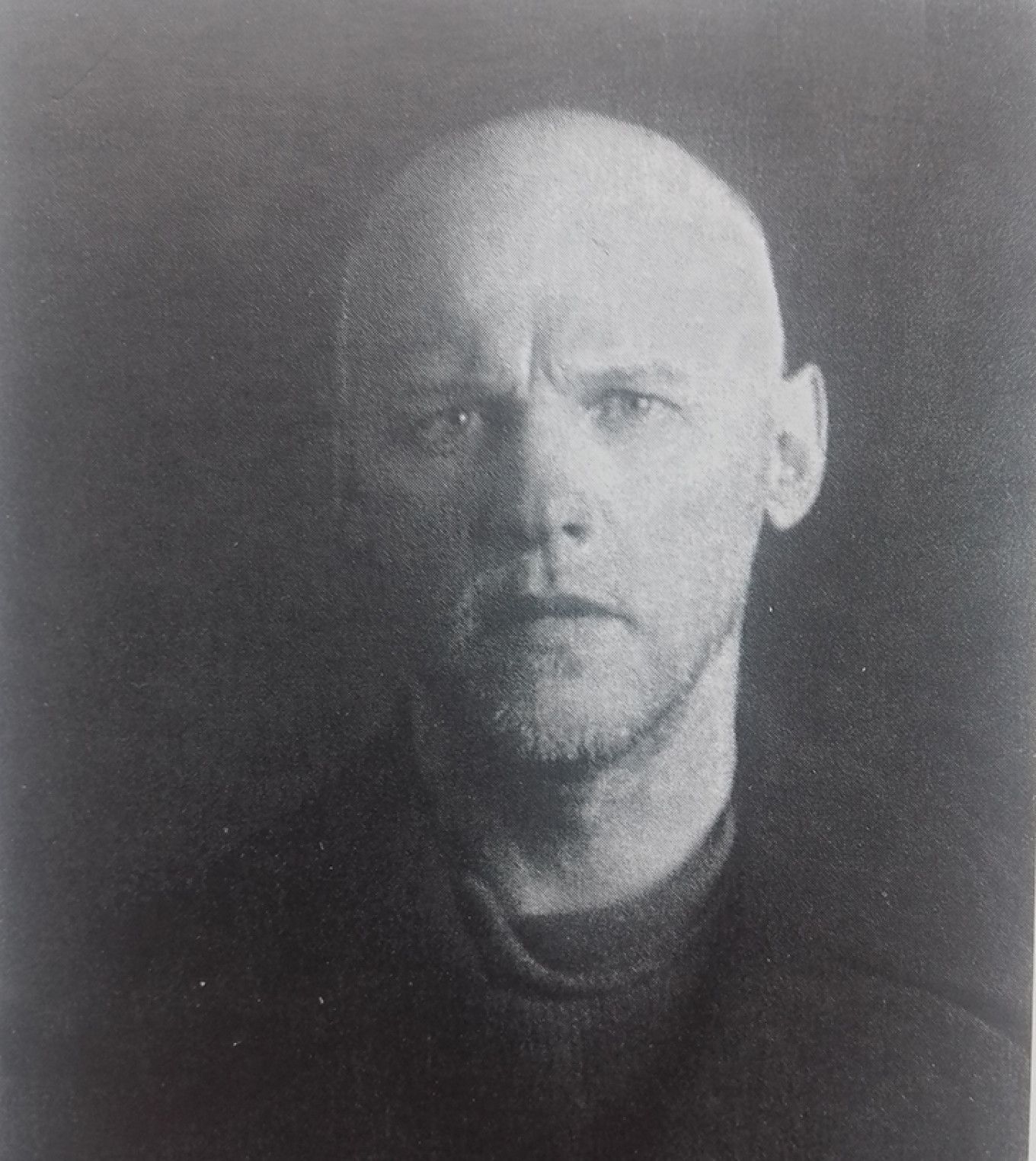

On Sunday, April 21, a small memorial plaque was installed in Moscow on the wall of an apartment house on Ultisa Myasnitskaya, where in 1938 the artist Aleksander Drevin was arrested and taken away to be eventually shot by the N.K.V.D. – the Soviet secret police.

Drevin was the most prominent artist killed in Stalin's 1937-38 operation against Poles and Latvians.

He had come to Moscow in 1914, joined the avant-garde group “The Jack of Diamonds” and participated in an exhibition of Latvian artists to raise funds for refugees in Petrograd. In 1920, Drevin began to teach in the painting department of the Higher Art and Technical Studios (VKHUTEMAS) and remained loyal to this educational institution until it was closed in 1930. In the same year, he married one of the “Amazons of the Russian avant-garde” — artist Nadezhda Udaltsova. They would have one son, Andrei, who became a successful and well-known sculptor. Among his works is the monument to Ivan Krylov at Patriarch's Ponds.

Throughout the 1920s Drevin continued to teach, exhibit and travel around the country on painting expeditions. He never lost touch with his compatriots, and when the Latvian cultural and educational society “Prometheus” was created in Moscow in 1929, he immediately plunged into its work.

In January 1936, an editorial entitled “Muddle Instead of Music” was published in the newspaper Pravda. It strongly criticized Dmitry Shostakovich's opera “Lady Macbeth of Mtsensk District” for “formalism” and “anti-popular” sentiments. Pravda soon published a second, even more devastating article against Shostakovich, after which a meeting was held to discuss these articles at the Moscow Regional Union of Soviet Artists. Drevin spoke at the meeting in support of formalism, which he said harnessed the “great power of dreams.”

In July 1937, the “Prometheus” society was liquidated, and on Nov. 30, the N.K.V.D. issued order No. 49990 against the Latvian diaspora in the Soviet Union. The arrests began. Almost everyone in the troupe of the Latvian theater Skatuve was arrested and executed. During the Great Terror, 21,300 people of Latvian origin were arrested and convicted of crimes, and 16,575 were sentenced to death.

Drevin was arrested on Jan. 17, 1938. Three days later the interrogations began. “The investigation has evidence that you are hostile to the Soviet government. Is that right?” the interrogator asked. Drevin said he was. “I supported formalism in art and opposed socialist realism,” he is reported to have said. “When I was instructed to adhere to socialist realism, I felt that my rights were infringed upon by the Soviet government, which was not permitting people to work freely. I believed the state was oppressing artistic freedom.”

During his interrogation on the next day, Drevin “acknowledged” his guilt of “participating in a counterrevolutionary nationalist organization of Latvians in Moscow.” He also admitted being opposed “to socialist realism and presenting content and forms alien to Soviet reality in art, focusing on western fascist artists like Braque and others.” Drevin admitted that his works had “counter-revolutionary distortions,” and said, “Instead of portraying a cheerful, prosperous, joyful collective-farm life, I drew a hard, sad collective-farm reality.” During his trips to Latvian ethnic collective farms, Drevin allegedly "conducted nationalist agitation."

As a result, according to the indictment, the artist was accused of participating in the "fascist nationalist organization of Latvians in the Prometheus society"; "sabotage"; and "nationalist propaganda." He also was accused of directly participating in the planning of terrorist acts against the leaders of the Soviet government.

On Feb. 11, 1938, Drevin was sentenced to “highest measure of punishment.” He was shot at the Butovo Polygon on Feb. 26, 1938. He was 49 years old.

For many years his paintings and even his name were banned. But artists knew and remembered him. His paintings were hidden in the storerooms of the Tretyakov Gallery and the Russian Museum. And they were lovingly preserved by his wife and son. When Drevin was arrested, Udaltsova said the paintings in the apartment were hers, so the family was able to save most of the artist’s works.

In 1957, Drevin was rehabilitated “for lack of evidence of a crime.” Art lovers were able to see his works for the first time since his death in 1959 at a retrospective exhibition of works of artists called the Latvian Red Riflemen, held in Riga. His first exhibition in Moscow took place only in 1971 at the State Museum of the Peoples of the East. In 2003 large exhibition of Drevin’s works was held at the Tretyakov Gallery.

The works of Alexander Drevin are in the collections of the Tretyakov Gallery, the State Art Museum of Latvia, and the Russian Museum in St. Petersburg.

A Message from The Moscow Times:

Dear readers,

We are facing unprecedented challenges. Russia's Prosecutor General's Office has designated The Moscow Times as an "undesirable" organization, criminalizing our work and putting our staff at risk of prosecution. This follows our earlier unjust labeling as a "foreign agent."

These actions are direct attempts to silence independent journalism in Russia. The authorities claim our work "discredits the decisions of the Russian leadership." We see things differently: we strive to provide accurate, unbiased reporting on Russia.

We, the journalists of The Moscow Times, refuse to be silenced. But to continue our work, we need your help.

Your support, no matter how small, makes a world of difference. If you can, please support us monthly starting from just $2. It's quick to set up, and every contribution makes a significant impact.

By supporting The Moscow Times, you're defending open, independent journalism in the face of repression. Thank you for standing with us.

Remind me later.