MAGAS — More than anything else, Zakri Mamilov is disappointed with Moscow. Why, he asks, has the Kremlin remained silent?

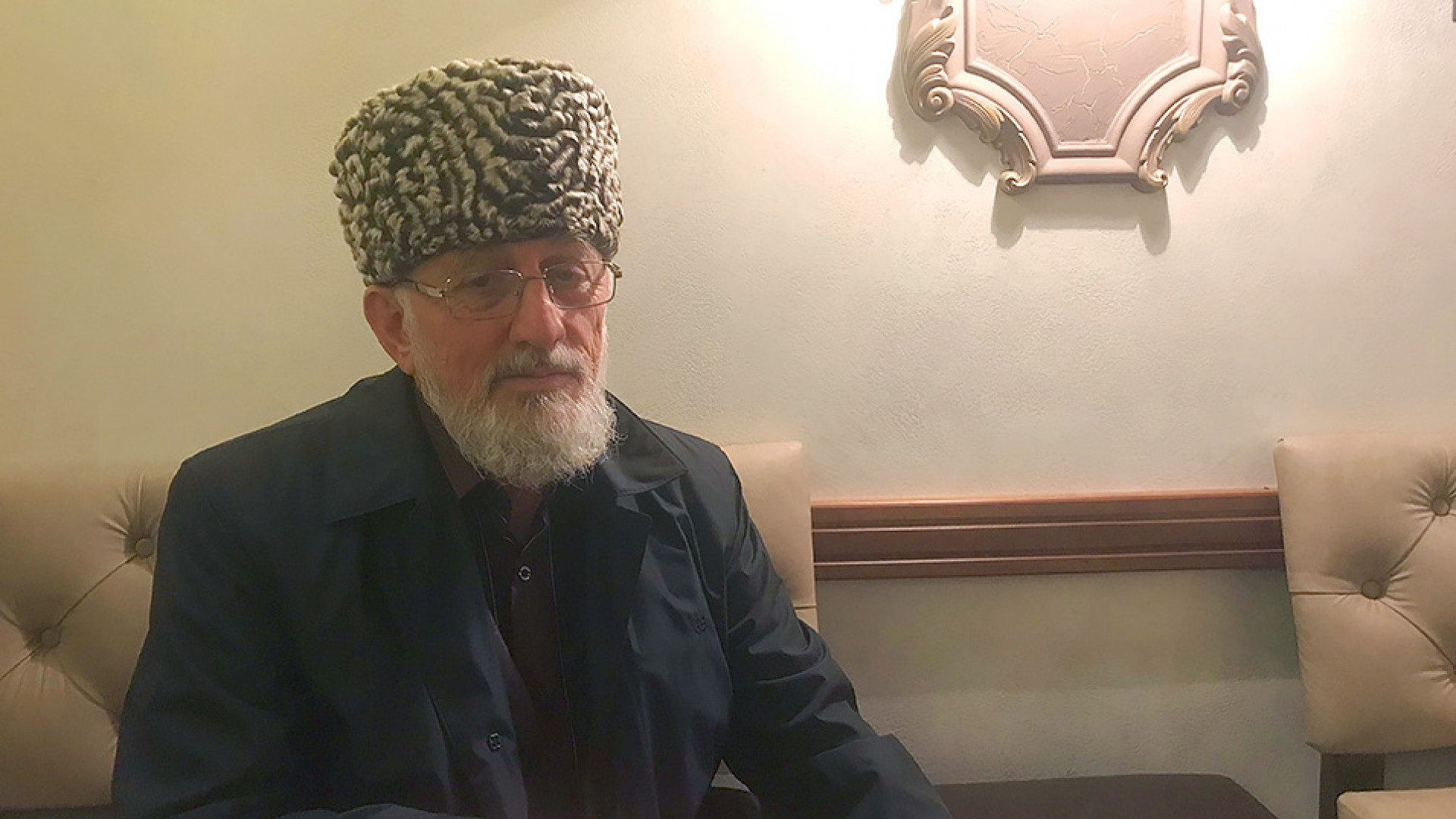

“It has outraged me to the depths of my soul,” the Ingush deputy who ran in recent elections as a candidate for the ruling United Russia party said on Monday. “Ingushetia is a subject of the Russian Federation. And when we are in the midst of such trouble, the Kremlin and state media have ignored us.”

Mamilov was referring to an Oct. 4 land-swap agreement with the neighboring republic of Chechnya that has roiled Ingushetia for the past weeks. In Magas, the republic’s capital, tens of thousands of protestors have taken to the streets.

The swap, they say, should be annulled because it was pushed through undemocratically. The Ingush and their representatives, they claim, weren’t consulted. They also believe it was a raw deal: Some estimates have shown that Ingushetia, already Russia’s smallest region, gave up 26 times more territory than Chechnya.

On Monday, Mamilov recalled hearing rumblings about the swap on social media long before Yunus-bek Yevkurov, the head of Ingushetia appointed by President Vladimir Putin, even informed deputies on Sept. 26 it was taking place. When Yevkurov finally did make the announcement, Mamilov said, he also made clear that he had already signed the agreement.

In response, deputies pushed for an opportunity to ratify it. On Oct. 4, Yevkurov allowed them to vote anonymously. Worried that their votes could be falsified, the deputies showed each other their ballots: “A minimum of 10 had voted against” the swap, Mamilov said. But when Yevkurov announced the results, there were only three “no” votes. Fifteen deputies have since signed a document seen by The Moscow Times attesting they voted against ratifying the deal.

When deputies exited the Assembly to announce the news, several hundred protestors gathered outside erupted in anger. To clear the crowd, security forces fired automatic weapons into the air. All the signs pointed to local authorities using force to quell further unrest.

But what has unfolded over the past two weeks has stunned protestors and outside observers alike, who say that the demonstrations are unprecedented in Putin’s nearly two-decade rule. They also say that the unrest could lead to conflict and that the Kremlin must take urgent measures.

Unprecedented protests

At the scene of the protests on Monday, “well over 1,000 people” milled about at different points throughout the day, estimated Tanya Lokshina, the Russia program director at Human Rights Watch, who was present.

Speakers took turns addressing the crowd, which had been sequestered to a barricaded square along the main street since the protests were sanctioned by authorities on Oct. 7. Those voices unanimously spoke about their land being given away without their consent.

Territorial questions are sensitive for the Ingush. In 1944, Josef Stalin abolished Ingushetia and deported its residents en masse to Central Asia. When the republic was restored 13 years later, it had lost 20 percent of its original territory to neighboring republics. The Ingush maintain that the land belongs to them, and the recent swap comes as another blow.

On Monday, protestors emphasized the sacred nature of their land. The current land swap, they said, gave Chechnya many of their ancestral “birth villages.”

Accentuating the point, Ruslan Albakov-Myarshkhin, a local human rights defender, recounted his grandfather’s final breaths. Having been displaced by Stalin to Azerbaijan in 1944, he took a plane back to Ingushetia instead of remaining on his deathbed.

“He died en route,” said Albakov-Myarshkin. “But we were still able to drive his body to his birth village and bury him there.”

At the scene of the protests, Lokshina said that the situation reminded her of the mass demonstrations in Moscow in 2011-12. Those erupted after it became clear that Putin had gamed elections so he could stay in power by swapping seats with Prime Minister Dmitry Medvedev.

“Just like then, the people today came out to the square because they felt lied to, they feel that their opinions don’t matter, that this decision — a very emotional one — was made without them, without authorities ever even trying to maintain some illusion that they were part of the process,” Lokshina said.

Protesters in the predominantly Muslim republic on Monday spent much of the day praying. Local police supervising the proceedings joined too. That police and protestors have at times seemingly united has been one of the hallmarks of the protests so far: Last week, Ingush security forces even prevented federal security forces from entering the protest grounds.

“It is unprecedented that parts of the elite and parts of the siloviki” — officials with ties to law enforcement — “have supported protestors,” said Yekaterina Sokirianskaia, director of the Conflict Analysis and Prevention Center think-tank. “Not just in this region, but anywhere in the country under Putin.”

That the president has not yet used force to disperse demonstrators has come to them as a surprise.

“That first night, when the protests weren’t yet sanctioned, we were expecting troops and siloviki to come down and leave our heads on the ground,” said Azmat Archakov, a 57-year-old pensioner.

Isabel Yevloyeva, a local journalist turned activist, speculated that perhaps the president is worried about incurring additional Western sanctions. But according to organizers, the protests have not been quashed because, from the outset, their message has not targeted authorities.

“We are of course concerned about other problems,” said Bagauidin Khautiev, 28, a protest leader and the head of the Council of the Youth Organizations of Ingushetia. “We have the highest rate of unemployment in Russia, we are second to last place in quality of life, we have rampant corruption, we can’t vote for the head of our republic, we have low quality of medicine and we have a high death rate of newborns.”

“But today all we are saying is this: Give us back our land,” Khautiev added. “If we start going in different directions, everything will be ruined.”

The past two weeks, however, have not all been smooth sailing for those gathered in the Ingush capital.

While the demonstrations have been allowed to continue, protest leaders said they have faced unannounced, middle-of-the-night searches of their homes and seizures of their cell phones and computers. Others have been fined for participating in unsanctioned protests or are facing criminal charges. Others said they have been pressured into leaving their jobs.

Outsiders have been subjected to pressure, too.

On Monday, Amnesty International reported that one of its researchers was abducted on Oct. 6 in Magas, where he was observing the protests. He was then stripped, threatened, beaten, abused and threatened with mock execution.

Still, for now, Putin has given no indication that authorities will invoke a broader crackdown: In an interview with the independent radio station Ekho Moskvy last week, Yevkurov, the head of the republic, said that Putin had advised him to not use force.

The situation could nonetheless escalate whether or not the instigator is the Kremlin, says Sokirianskaia.

“It is very wise that the Kremlin has so far decided against using force which could have greatly escalated the situation,” she said. “But there are other risks too: If they let this simmer for too long, new dynamics could be unleashed, increasing inter-ethnic tensions. We are already seeing some signals.”

Many in the neighboring republic of Chechnya, Sokirianskaia said, see the protests as having an anti-Chechen agenda. She pointed to a YouTube video that claims to speak on behalf of the Ingush denouncing Chechen strongman Ramzan Kadyrov that has garnered hundreds of thousands of views. And Kadyrov himself has said it “suits them to fight.”

“Such provocations on either side can escalate tensions, that can potentially spill over to other regions," Sokirianskaia said. “I understand that in Moscow security forces are taking measures to prevent this from happening. The authorities need to start constructively engaging with the protesters as quickly as possible.”

Carving up the republic

On Tuesday, Putin sent his representative in the Northern Caucasus Alexander Matovnikov and his domestic policy chief Andrei Yarin to meet with eight protest leaders. But after a two-and-a-half hour meeting, the locals left dejected. According to a representative of their delegation, the Moscow officials underscored that the law had already gone into force.

“We’re going to inform the people and they will decide what we do next,” said local clan council leader Malsag Uzhakhov by phone after the meeting. With the protests only sanctioned until Wednesday evening, he acknowledged that the “situation is becoming more tense.”

Several hours after the Tuesday meeting, Yevkurov announced that the protest leaders would be getting another meeting on Wednesday: this time with a government commission examining the land transfer question.

Earlier, Barakh Chemurziev, a member of the protestor delegation, had said that only an annulment of the agreement, not any amendments, would end the protests.

“If the authorities believe that we will give up anytime soon, they are wrong,” he said over shashlik and tea at Cafe Del Magas, a restaurant adjacent the protest area that has become a de-facto gathering point for protestors and local police alike.

“The people gathered here aren’t some hipsters in St. Petersburg,” he said. “These are strong, broad-shouldered men who have served in police and militia forces. These people can defend themselves with their bare hands.”

And because authorities crossed “a red line they should never have crossed,” Chemurziev said, the Ingush will not stop protesting, whether the authorities allow their demonstrations or not.

“It is no mistake that, on a map, our land looks like a bone,” he said. “Wolves keep taking bites out of our meat. We need to stop being weak and start defending ourselves.”

A Message from The Moscow Times:

Dear readers,

We are facing unprecedented challenges. Russia's Prosecutor General's Office has designated The Moscow Times as an "undesirable" organization, criminalizing our work and putting our staff at risk of prosecution. This follows our earlier unjust labeling as a "foreign agent."

These actions are direct attempts to silence independent journalism in Russia. The authorities claim our work "discredits the decisions of the Russian leadership." We see things differently: we strive to provide accurate, unbiased reporting on Russia.

We, the journalists of The Moscow Times, refuse to be silenced. But to continue our work, we need your help.

Your support, no matter how small, makes a world of difference. If you can, please support us monthly starting from just $2. It's quick to set up, and every contribution makes a significant impact.

By supporting The Moscow Times, you're defending open, independent journalism in the face of repression. Thank you for standing with us.

Remind me later.