Safer. Greener. Cleaner. Better. This is what Sergei Sobyanin has promised Moscow if he is re-elected as the city’s mayor on Sunday for another five-year term.

Or, put another way, the whirlwind changes that the capital has already seen under his watch will go on.

Since Sobyanin was selected for the post in 2010, Moscow has undergone a drastic makeover. Public transport has been revamped and expanded; sidewalks have been widened and repaved; roads have been renewed and equipped with bike lanes; waterfronts have been cleaned up and remodeled; and parks all over the city have been refurbished — all at a vast expense.

Despite these myriad improvements, his critics are unimpressed: Behind Moscow’s Western-style veneer, they argue, are Sobyanin’s Soviet-style governance tactics along with a long tradition of cronyism and corruption.

Nonetheless, Sobyanin has only shored up his position as the proprietor of Moscow.

The last time Sobyanin ran for office, five years ago, he was nearly forced into an unexpected run-off against opposition leader Alexei Navalny. This time around, the mayor has sidelined the opposition.

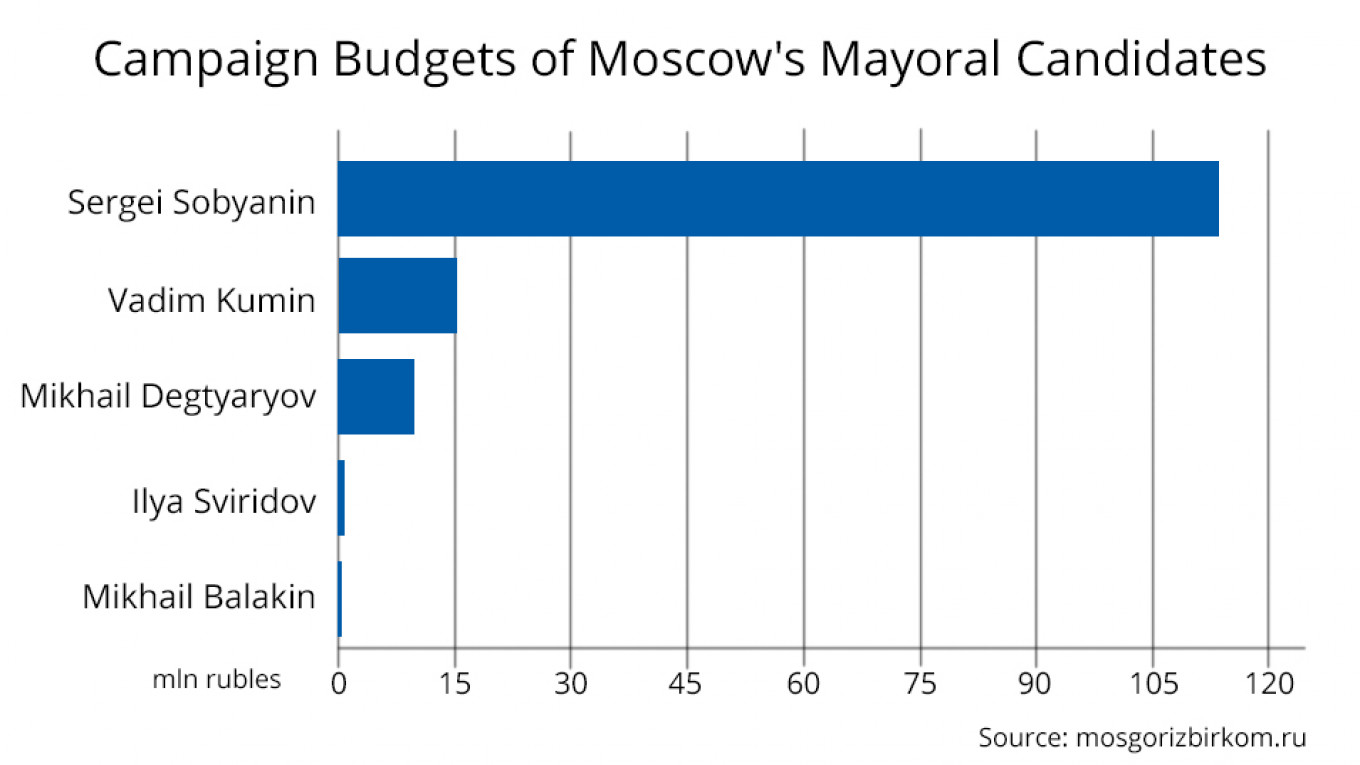

Opposition candidates have been blocked from participating (Navalny himself will spend election day in jail for organizing unsanctioned demonstrations earlier this year) and Sobyanin’s campaign budget is about 10 times the size of his nearest rival (none of whom are polling above 1 percent). When voters head to the polls on Sunday, nearly 70 percent (of an expected 31.8 percent turnout), according to state-run pollster VTsIOM, are prepared to cast their ballots for the incumbent.

“He’s in a comfortable position,” says Alexei Levinson of the independent Levada Center pollster. “He’s not worried about anyone taking his throne.”

Above all, Sobyanin has the Kremlin’s backing. “The president values [Sobyanin] highly and supports his work,” Kremlin spokesman Dmitry Peskov told The Moscow Times ahead of the vote.

That his political stature has risen so dramatically has stunned observers. Just eight years ago, when Sobyanin was parachuted from the regions into the capital to turn the city around, he was all but unknown.

Political pragmatist

“He has always been a political pragmatist,” says political analyst Nikolai Petrov of Sobyanin, who was born in 1958 in an ethnic Mansi village in oil-rich western Siberia.

Petrov, who is an expert in Russia’s regions, has followed Sobyanin’s political career since the early 1990s, which Sobyanin spent mostly in low-ranking positions in his native Siberia and the Urals.

Key to his climb up the bureaucratic ladder, Petrov believes, have been his longtime connections with Vladimir Putin, which go as far back as when the president was still an aide in St. Petersburg Mayor Anatoly Sobchak’s administration.

As the independent RBC outlet reported in 2016, one of Sobyanin’s closest confidants, Vladimir Kalashnikov, and the man famous for recommending Putin to Sobchak, Nikolai Yegorov, have been close friends since the early 1990s. Today, they are both partners in a Tyumen-based oil company.

Sobyanin himself helped the company get off the ground back in 2005, RBC found, when he was governor of the Siberian region — his first significant political role. Soon after, Putin summoned Sobyanin to the capital, naming him the head of his presidential administration.

Meanwhile, Moscow’s then-mayor, Yury Luzhkov, was coming to the end of his leash with Russia’s elites. The bombastic, colorful politician had been running the city since 1992, shortly after the fall of the Soviet Union. As Moscow’s population swelled with the real estate boom of the early 2000s, Luzhkov failed to manage the city’s infrastructure. Just before his ousting in 2010 by President Dmitry Medvedev — officially on corruption charges — the city suffered the longest traffic jams among major global cities.

When Medvedev named Sobyanin mayor, the transplant soon began working on improving the city’s underground rail network. “Sobyanin received a large chunk of federal money to build up the city’s metro system,” says Petrov. “At the time, it was seen as a move to make sure Sobyanin did not look weak.”

Riding a wave of modernization promoted by Medvedev, Sobyanin also had other improvements in mind, pledging to transform Luzhkov’s Moscow — famous for its traffic, garish buildings and countless commercial kiosks — into a “more European” city. In 2011, he tapped Sergei Kapkov, a State Duma deputy, to renew Gorky Park — to Moscow what Hyde Park is to London, or what Central Park is to New York.

The improvements — potholes and stray dogs swapped for bike lanes and a pleasant river embankment, among other changes — were an immediate hit. Not long after, Sobyanin promoted Kapkov to become the city’s culture minister.

“He figured out what Moscow wanted and ran with it,” Kapkov recalls today. “If I was the ideas guy, he was the one to make sure things got done.”

Many critics, however, argue that Sobyanin has been empowered to refashion the city into one that could appease disaffected liberals following the quashing of mass 2011-2012 protests. As evidence, they point to his colossal budget totaling nearly 25 percent of the rest Russia’s regions put together.

After the annexation of Crimea in 2014 and amid the Kremlin’s saber-rattling rhetoric, Kapkov resigned. (It had seemed as if Sobyanin had grown “tired of me,” Kapkov told The Moscow Times). Some wondered if Moscow’s brief experiment with Western-style renewal was over.

But even as Russia’s relations with the West have soured, Sobyanin has continued working with leading Western architects (Renzo Piano, Rem Koolhas) and companies (McKinsey & Company, the Boston Consulting Group). The mayor’s latest prestige project, Zaryadye Park, at walking distance from Red Square and the Kremlin, was designed by Americans.

Paternalistic traditions

Sobyanin has piled up praise from those on high for his prestigious projects: At Moscow’s Urban Forum in July, Putin said the capital had become a “true trendsetter” among modern cities under Sobyanin. But his policies have at the same time elicited some of the loudest protests. According to Levada Center’s latest figures, 48 percent of Moscow residents do not approve of his work.

To his critics, Sobyanin is a symbol of everything that is wrong with Putin’s regime, including a top-down governance style that bestows gifts upon the people without ever consulting them.

One of the most prominent examples of this was a spontaneous, dead-of-night demolition of dozens of Luzhkov-era retail pavilions in 2016. Sobyanin ordered them razed, calling the stalls “unsightly.”

But if there has been a single issue that has most stirred dissent to Sobyanin, it has been his plan to tear down thousands of Soviet-era apartment buildings, which is set to kick into high gear after his expected re-election. According to the plan, some 1.5 million residents will be resettled into new buildings in their same neighborhoods. In late spring of 2017, thousands took to the streets to protest.

One of those protesters was Gleb Smyslov, a 48-year-old business consultant who was born and raised on the historic Arbat Street. His main issue with Sobyanin, he told The Moscow Times, is that it sometimes feels as if he “breaks citizens over the knee” to get things done.

Even Sobyanin admitted as much in a recent interview with the Kremlin-friendly Expert magazine. “Paternalism and reliance on the state have been strong traditions since Soviet times,” he said.

For Ilya Oskolkov-Tsentsiper, the founder of Strelka institute, which has been a flag-bearer of Moscow’s urbanist movement, the tradition harkens back even further, to the turn of the 18th century.

“We had a tsar who wanted to build St. Petersburg and said he would make it more European than any city Europe has even seen,” he said. “And if the citizens didn’t behave the right way, well, he said, we’ll just chop off their heads.”

Ultimately, many Muscovites simply do not trust their mayor. They suspect his urban renewal drive is simply a ploy to cover up corruption.

There is evidence to back up those concerns. For instance, RBC has reported that several contractors are linked to relatives of Deputy Mayor Pyotr Biryukov. And just last week, the independent Meduza outlet reported that Kalashnikov, the longtime Sobyanin confidant, is earning money off the mayor’s drive to replace trolleybuses with electric buses throughout the city.

And while Moscow’s budget has ballooned since Sobyanin’s first year in office — nearly doubled, according to City Hall — Ilya Yashin, a local municipal deputy who has long opposed Sobyanin, is concerned that the share spent on social services like healthcare and education is insufficient.

“They are taking money that should be going to doctors and teachers and have shifted it to construction projects,” Yashin alleged. “It’s easier to steal this way than just taking directly from those people’s pockets.”

A carefully curated image

Not unlike Putin himself — who was largely an enigma when he rose to power in the early aughts — those who know Sobyanin describe him as unremarkable and difficult to read.

“He’s like a ghost,” said a person who has worked closely with City Hall on a number of renewal projects but asked not to be named. “You sometimes can’t even tell when he’s in the room.”

Central to his rise, observers say, is that, as zealous as he has been about refashioning Moscow, he has also delved equally into fashioning a propaganda empire that only Putin’s rivals.

Last fall, Alexei Kovalev, a Russian journalist and media watcher, found that City Hall had instructed local Moscow outlets to mention Sobyanin’s name three times and include one of his quotes in any story about him.

In addition, the mayor has a network of sham websites, Kovalev said, that no one is reading and are constantly writing about him. “And all of this is to affect Russia’s main ratings website, Medialogia, because he is the most dull, uninspiring person in the world who rarely makes any public appearances or statements, but our ratings are based on mentions in the media,” Kovalev said.

As of the latest Medialogia ratings in July, Sobyanin is cited by bloggers the most out of any public personality — nearly twice as much as second place Chechen leader Ramzan Kadyrov — who is “constantly on social media,” as Kovalev put it.

“It’s probably the most expensive and expansive image- building program that I have ever seen in Russian politics,” Kovalev says. “He’s gone from an obscure nobody to basically one of the most powerful and public people in Russia in just eight years.”

For some, everything he has done, even — including urban renewal — has been aimed at crafting an image.

Or, as Sergei Polyakov, a political analyst who is also helping run the campaign of A Just Russia party candidate Ilya Sviridov, put the point more unsparingly: “Everything he does is to please federal officials. But behind this nice facade that he’s built, there is a whole set of problems that are only growing.”

Political future

For years now, observers have wondered where next Sobyanin might end up in Russia’s political vertical.

As long ago as 2013, political analyst Yevgeny Minchenko noted that Sobyanin could be a palatable successor to Putin. "In the eyes of the elites, Sobyanin has an established, positive track record,” Minchenko said then. “They see him as a mediator who can safeguard their interests."

Today, Minchenko is wary of making predictions in Russian politics — after all, he notes, Sobyanin wasn’t chosen to be the mayor back in 2010 until the very last moment. But Minchenko does offer this much: “Sobyanin is one of the most powerful people in Russia.”

Some analysts, like Petrov, are less wary of forecasting the future. Pointing to unpopular pension reforms, announced this summer by current prime minister Medvedev, and which have seen Putin’s ratings fall sharply, Petrov said, “I don’t exclude that Sobyanin may be replacing Medvedev sooner rather than later.”

Whatever his next role, though, Petrov says Sobyanin is eyeing the long game.

“He has this northern style not only because of his inscrutable face, but also because he is a hunter, and a very specific one,” Petrov says. “He can sit in cover for many hours, without any rush, and without giving away his plans or ambitions. But when the time has come, he has always been ready to pounce.”

A Message from The Moscow Times:

Dear readers,

We are facing unprecedented challenges. Russia's Prosecutor General's Office has designated The Moscow Times as an "undesirable" organization, criminalizing our work and putting our staff at risk of prosecution. This follows our earlier unjust labeling as a "foreign agent."

These actions are direct attempts to silence independent journalism in Russia. The authorities claim our work "discredits the decisions of the Russian leadership." We see things differently: we strive to provide accurate, unbiased reporting on Russia.

We, the journalists of The Moscow Times, refuse to be silenced. But to continue our work, we need your help.

Your support, no matter how small, makes a world of difference. If you can, please support us monthly starting from just $2. It's quick to set up, and every contribution makes a significant impact.

By supporting The Moscow Times, you're defending open, independent journalism in the face of repression. Thank you for standing with us.

Remind me later.