The Moscow Times and Project1917 continue to share the most compelling stories of 1917.

In the fourth installment of the series, which takes place this week one hundred years ago, Gorky tweets about his personal life, Lenin talks business in letters to his lover and the leader of the State Duma describes how Russian powers used to operate in 1917 (clue: it's about the same as in 2017.)

Read previous episodes here.

February 13:

Kazemir Malevich writes down his thoughts on art, history and Russian life. His notebooks look like the personal Facebook an edgy artist might have today. He'd certainly get all the likes.

Color and number and sound rule the world.

Meanwhile in New York, Leon Trotsky is astonished by the conveniences of life in the United States. “Electric lights, a gas stove, a bath, a telephone, an automatic service-elevator.” These would have been unthinkable in workers’ districts in Europe!

We rented an apartment in a workers’ district, and furnished it on the instalment plan. That apartment, at eighteen dollars a month, was equipped with all sorts of conveniences that we Europeans were quite unused to: electric lights, a gas stove, a bath, a telephone, an automatic service-elevator and even a chute for the garbage. These things completely won the boys over to New York. For a time the telephone was their main interest; we had not had this mysterious instrument either in Vienna or Paris.

February 14:

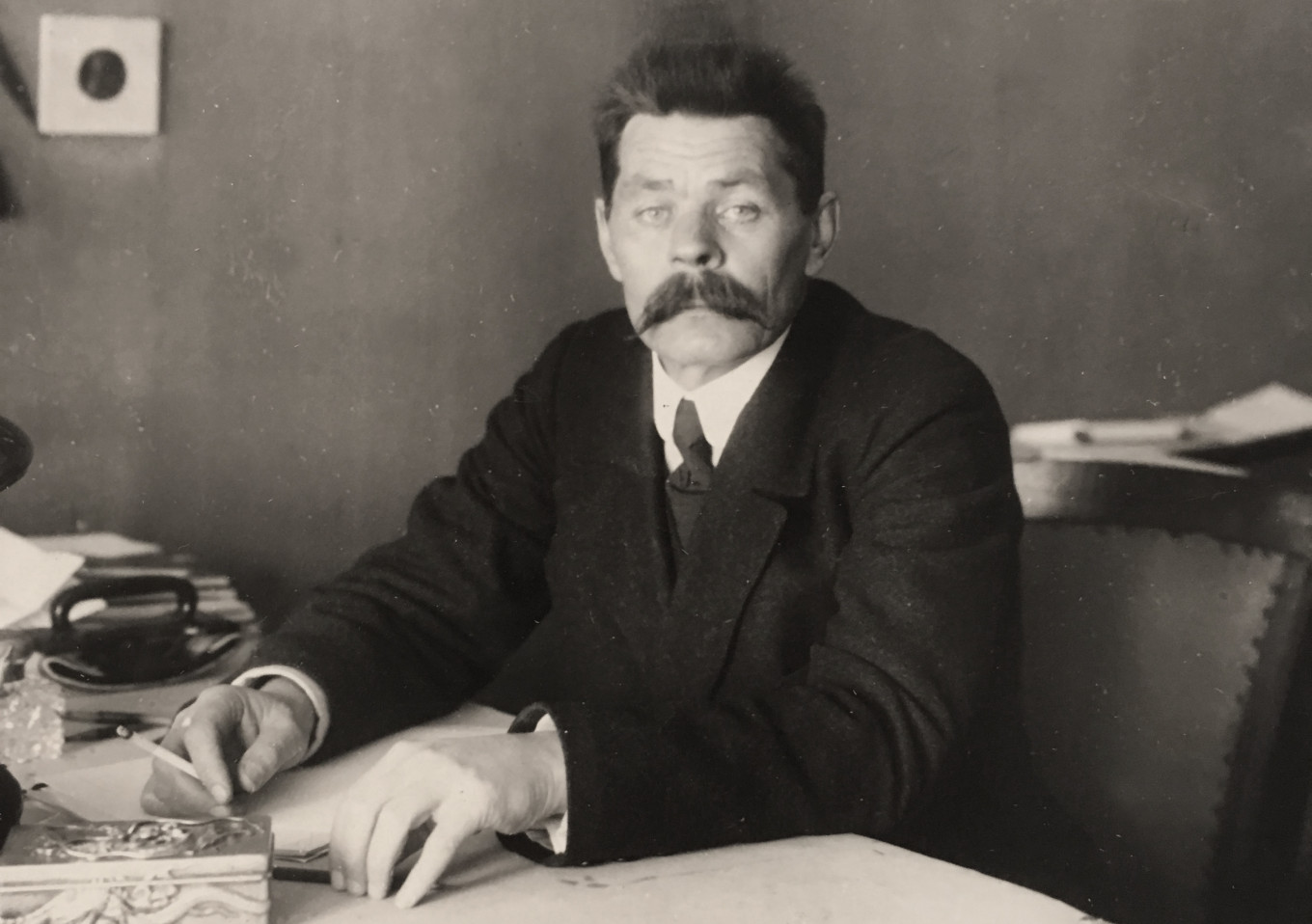

Maxim Gorky is feeling down, if his letters are anything to go by.

Life is becoming a nightmare — especially difficult for those who have no personal life. Personal life, a moderately dirty and uncomfortable place, is at least somewhere you can rest.

February 15:

Lenin is dry and as to the point in his letters to lover Inessa Armand as he is in any of his business letters to other revolutionaries. Revolution requires full concentration, don't you know? This is not a time for tenderness.

Dear Friend,

I am sending you a leaflet. Will you please translate it into French and English?

Please translate it in vigorous language, and in short sentences. Please write it in duplicate, on thin paper, and as clearly as possible to avoid misprints.

Yours, Lenin

February 17:

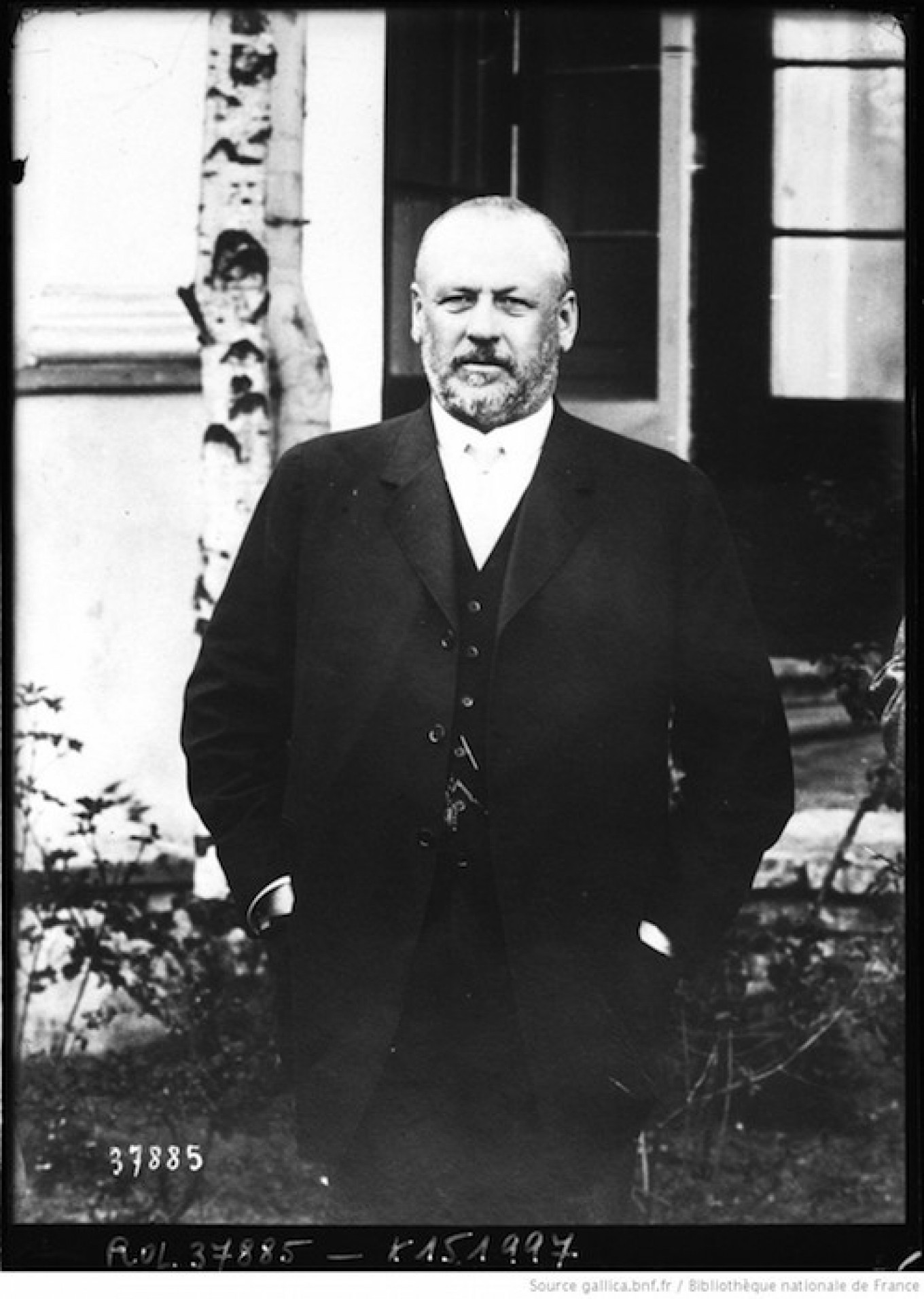

The head of the State Duma Mikhail Rodzyanko describes the way the Russian authorities operate. The strangest thing about this entry is that it was written in 1917, not 2017.

It is unthinkable that a doctor should be entrusted with the building of a bridge. It is likewise unthinkable that an engineer would be asked to cure patients. But it is even more inconceivable that the economic life of the country should be taken from the direction of those who are informed, and handed over to those who are, at best, amateurs, and at worst, pure ignoramuses.

A Message from The Moscow Times:

Dear readers,

We are facing unprecedented challenges. Russia's Prosecutor General's Office has designated The Moscow Times as an "undesirable" organization, criminalizing our work and putting our staff at risk of prosecution. This follows our earlier unjust labeling as a "foreign agent."

These actions are direct attempts to silence independent journalism in Russia. The authorities claim our work "discredits the decisions of the Russian leadership." We see things differently: we strive to provide accurate, unbiased reporting on Russia.

We, the journalists of The Moscow Times, refuse to be silenced. But to continue our work, we need your help.

Your support, no matter how small, makes a world of difference. If you can, please support us monthly starting from just $2. It's quick to set up, and every contribution makes a significant impact.

By supporting The Moscow Times, you're defending open, independent journalism in the face of repression. Thank you for standing with us.

Remind me later.