In his last visit to Ukraine as U.S. vice president, Joe Biden met on Monday with Ukrainian President Petro Poroshenko and Prime Minister Volodymyr Groysman, who heaped lavish praise on “dear Joe.”

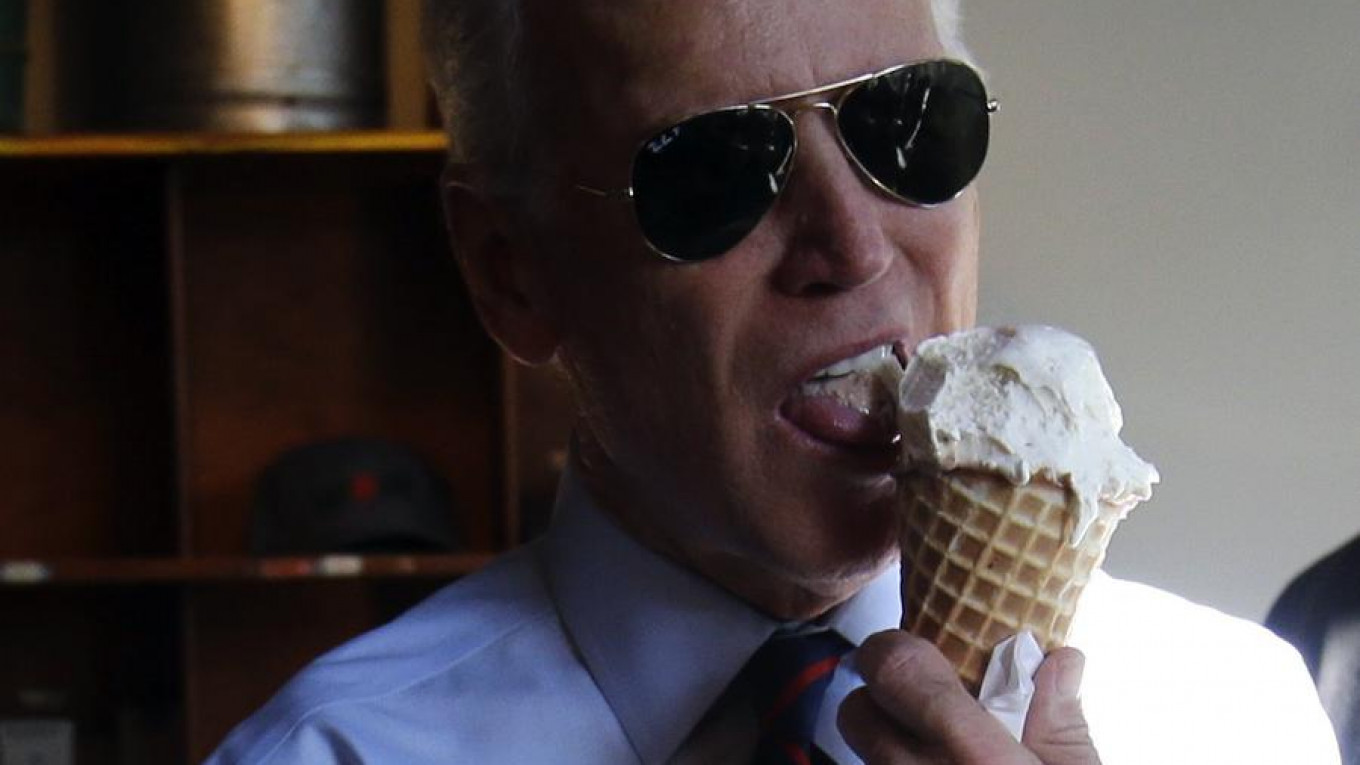

In the U.S., Biden is often portrayed in memes depicting the various impractical pranks he’d like to play on Donald Trump. Given the silliness of these jokes, it usually surprises Americans to learn that Biden has been Obama’s point man in Ukraine, where the vice president has played the role of the White House’s enforcer.

In his December 2015 address to Ukrainian parliament, Biden warned deputies that corruption was a cancer on Ukraine, and called on them to take action and not squander the opportunities created by the Maidan Revolution.

Among both elected officials and ordinary people in Ukraine, Joe Biden has wielded moral authority that’s usually absent from the country’s politics.

In Ukraine, Biden has also done more than just preach the virtues of good governance; when Poroshenko delayed in firing his corrupt pocket prosecutor, Biden threatened to withhold a $1-billion loan. Shortly thereafter, the prosecutor got the boot.

This was the sort of personal relationship Biden cultivated — one that could be warm and friendly, but very blunt, just as easily. It was a good mixture in Ukraine, where personal clout and candidness fuel projects at all levels of state and society.

In Ukraine, Biden often seemed to personify U.S. policy. The vice president made five trips to the country, following the Maidan protests, while President Obama never visited once. Whenever Biden left, he still maintained a strong presence in Kiev, phoning so often that he later joked, at his last joint press conference with Poroshenko, that he’d grown so accustomed to the Ukrainian president’s voice that he’ll need to keep calling him for a while more, simply out of habit.

Biden, of course, was never as powerful in Ukraine as he seemed. Though his trips were frequent, he didn’t deviate from the White House’s talking points. The vice president’s ability to accept limitations and speak in concert with the president made him a valuable asset to Obama, who acknowledged this service when awarding Biden the Presidential Medal of Freedom, reserved in recent administrations for just a handful of recipients, including Pope John Paul II.

This is not to say the Obama administration was always popular in Ukraine. The White House’s unwavering opposition to sending lethal military aid to Kiev, out of fear of escalating the conflict, was deeply unpopular in Ukraine. On this issue, U.S. Senator John McCain has far more support. More than once, when traveling through remote Ukrainian villages, I heard locals praise McCain over Obama.

But Biden’s continued involvement with Kiev was always a clear signal that Ukraine continued to be a high priority and would not be forgotten, whatever the momentary disagreements in Washington.

Now, as Obama and Biden step down, Ukraine will have to fight to stay on the international agenda.

Biden’s exit marks the end of an era for Ukraine. Already, generally less active diplomats have replaced the ambassadors who were in office during the Maidan protests. That previous generation of statesmen experienced firsthand the heights of activism in Ukrainian society and the influence foreign diplomats could wield with a well-placed comment. These men and women had no qualms about publicizing their displeasure, when leaders entered government and failed to live up to their promises.

One of the most active diplomats from this era was U.S. Ambassador Geoffrey Pyatt, whose successor, Marie Yovanovitch, is noticeably absent from Twitter and the media more broadly. Yovanovitch is perfectly competent, but it’s hard to imagine her summoning oligarch Igor Kolomoisky, as Pyatt once did, after Kolomoisky berated a Radio Free Europe journalist.

Naturally, diplomats work to maintain a delicate balance, but in the imperfect world of Ukrainian politics it's their criticisms that often provide a much-needed check on corruption and abuses of power.

In his final statement to the Ukrainian Presidential Administration, Biden again called on the country’s leaders to take personal responsibility for fighting corruption and pledged American support for sanctions on Russia, until the Minsk Protocols are fully implemented. That pledge, however, looks less absolute than it once did, with President-elect Donald Trump saying he might end sanctions in exchange for a reduction of Russia’s nuclear arms.

Despite the challenges since Trump’s surprising victory, Biden has committed himself to trying to ensure a smooth transition. This last trip to Ukraine had less to do with resolving urgent business than convincing the Trump administration that Ukraine should remain a priority for U.S. foreign policy.

At the end of the press conference, as Biden and Poroshenko left the stage, a reporter from The Atlantic asked the vice president how successful he expects to be in convincing Trump to stick with Kiev. “Hope springs eternal,” Biden answered.

Ian Bateson is a journalist living in Ukraine. His work has appeared in The New York Times, The Guardian, Foreign Policy, and Reuters.

A Message from The Moscow Times:

Dear readers,

We are facing unprecedented challenges. Russia's Prosecutor General's Office has designated The Moscow Times as an "undesirable" organization, criminalizing our work and putting our staff at risk of prosecution. This follows our earlier unjust labeling as a "foreign agent."

These actions are direct attempts to silence independent journalism in Russia. The authorities claim our work "discredits the decisions of the Russian leadership." We see things differently: we strive to provide accurate, unbiased reporting on Russia.

We, the journalists of The Moscow Times, refuse to be silenced. But to continue our work, we need your help.

Your support, no matter how small, makes a world of difference. If you can, please support us monthly starting from just $2. It's quick to set up, and every contribution makes a significant impact.

By supporting The Moscow Times, you're defending open, independent journalism in the face of repression. Thank you for standing with us.

Remind me later.