Your homeland is where you live,” the Soviet commissar tells the exhausted soldiers. “But the Fatherland is about how you live.”

Outnumbered and under-equipped, 28 men brace themselves for a battle to halt the Nazi advance on Moscow. The commissar’s lesson on patriotism is a timely reminder of why they are there, shoulder-deep in the freezing trenches and facing almost certain death.

Like much else in “The Panfilov 28,” a new state-sponsored blockbuster based on a famous Soviet WWII legend, the scene blurs fact and fiction.

The story of the Panfilov guards had clear propaganda value for the Soviet regime. It was a tale of heroic World War II self-sacrifice. Even after the fall of the Soviet Union, the story was widely accepted as fact. The reality, however, was more complicated. According to documents published by Russia’s state archive last year, the number of soldiers involved in the actual battle in 1941 was closer to ten thousand than 28. There were also other crucial differences.

Those caveats have not made it into the film or been acknowledged by state officials, which has led some leading academics to accuse the government of deliberate deception.

“It’s very bad when the government lies,” Russia’s former chief archivist Sergei Mironyenko told the RBC television station. “When the state makes up heroes instead of naming the real ones, it undermines faith in history.”

The Kremlin, however, is unapologetic. Under the leadership of the ultra-patriotic culture minister Vladimir Medinsky, who himself is a trained historian, Moscow has peddled a view of the past as a political instrument. By his own admission, historical accuracy should give way to a version of the past that stresses national unity and confers legitimacy on the current regime.

“Even if the Panfilov story was made up from start to finish, this is a sacred myth that should remain untouched,” Medinsky has argued. Challengers of that view, such as Miryonenko,who was demoted following the controversy over the Panfilov myth in March, are “scum bags,” he said.

Statue Mania

While World War II myths have long been considered sacred ground, the Kremlin this year showed that there was no historical period too distant, or controversial, to mine for symbolism.

A statue of Prince Vladimir, who is credited with bringing Christianity to ancient Rus, has long stood on the slopes of the Dnepr River in the Ukrainian capital, Kiev. Amid a protracted fallout with their immediate western neighbor, the Kremlin wanted to reclaim ownership of the tenth century ruler. So it installed its own 17-meter Vladimir holding a giant Orthodox cross right outside the Kremlin walls. The unveiling of the statue in November was attended by the highest Kremlin officials, including Vladimir Putin and Patriarch Kirill, his ally.

Critics have dismissed the statue as an eyesore. UNESCO, the world heritage organization, warned it would have a “negative impact” on the landscape. Prominent Russian architect Yevgeny Asse put it more bluntly: “It’s like driving a nail through someone’s skull,” he said on the Ekho Moskvy radio station.

A month earlier, the southern city of Oryol erected Russia’s very first statue of Ivan the Terrible, widely known for the deaths of thousands of people and the murder of his own son. Ignoring local protest and controversy, regional governor Vadim Potomsky recast the bloody ruler as Putin’s glorious predecessor. “We have a strong president who has forced the world to respect Russia, just like Ivan the Terrible did in his time,” he declared in a passionate speech.

The year also saw statues of Stalin pop up around the country as patriotic citizens took their cue from their government.

According to historian Nikita Sokolov, the continuous sparring over historical films and statues is less a sign of disagreement over Russia’s past than clashing views over its future. “Russian society sees itself as being tied to the country’s historical fate, so the issue of who is the hero and who is the villain here is really important,” he says.

Sokolov is one of the founders of the Free Historical Society, a group of independent academics pressing for the state to withdraw from historical debates. But interference seems to be growing.

In December, filmmaker Nikita Mikhalkov, a friend of the president, went on the attack against a museum devoted to Russia’s first president, Boris Yeltsin. According to Mikhalkov, The Yeltsin Center was “indoctrinating” visitors with ideas that destroy the “national consciousness.” Its sin had been to portray the '90s — a period of both unprecedented freedom and instability in Russian society — too positively.

The celebrity director called for the government to review the museum’s work. It did not take long for Medinsky to back the proposal, accusing the center of pandering to the “dogma of European civilization.”

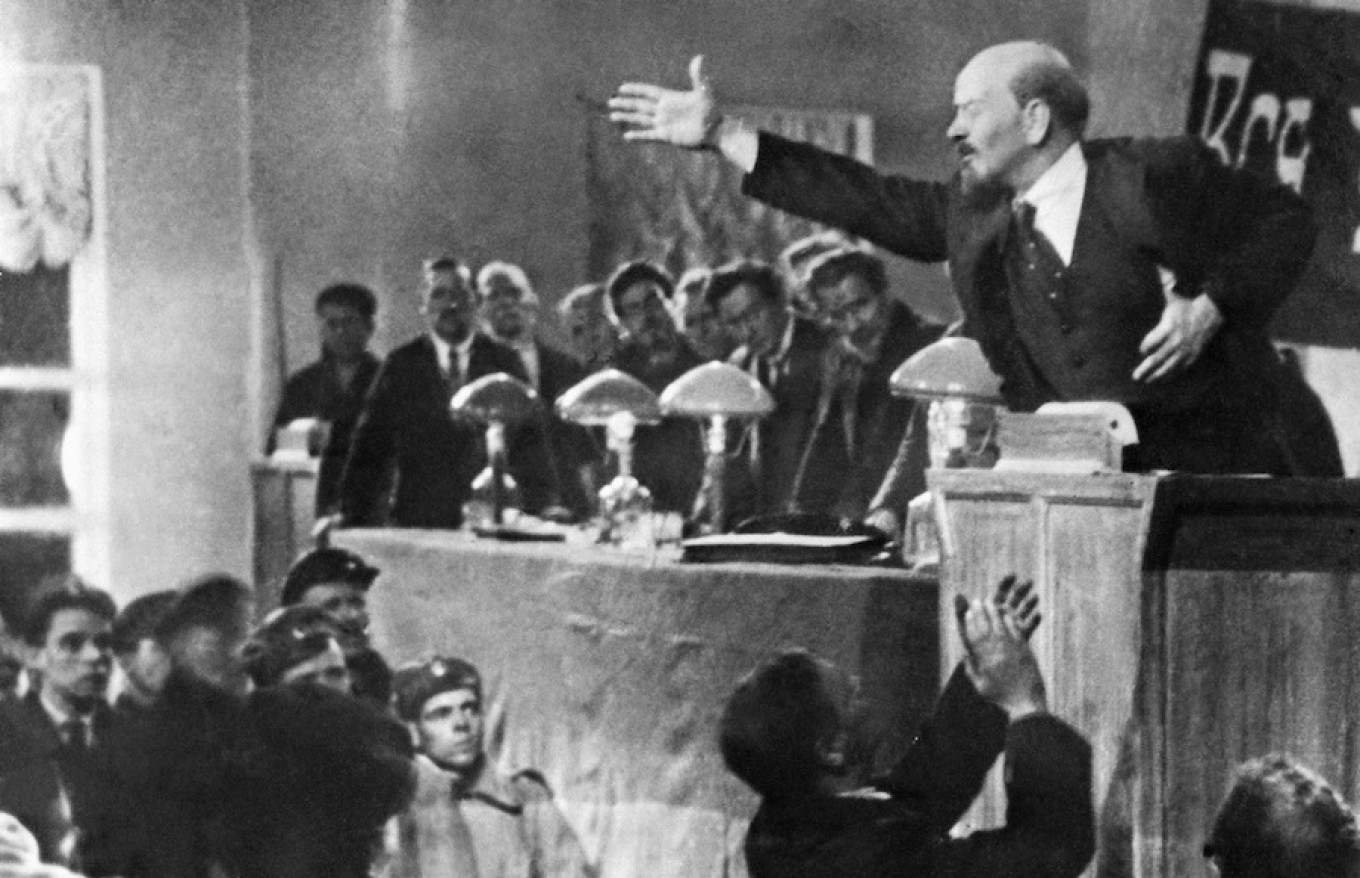

Awkward Anniversary

While sparks fly over how to interpret even Russia’s recent history, the Kremlin is unlikely to offer a coherent position on next year’s grand event: the centennial of the 1917 upheaval that toppled the aristocracy and founded the Bolshevik regime.

Putin’s regime is no fan of popular uprisings, having itself gone to great pains to quell any form of protest. The resurgence of the Russian Orthodox Church has also fanned renewed sympathies for the Romanov dynasty, particularly for the canonized Tsar Nicholas II. In what may be a warning of things to come, the ultra-loyalist Duma deputy Natalya Poklonskaya made headlines this year after requesting an investigation into a film about a ballet dancer reputed to have been Nicholas’ lover. Even though Poklonskaya had never seen the film, which is still being produced, she warned it could tarnish his image.

At

the same time, however, the Kremlin is unwilling to unequivocally

condemn the events the revolution set in motion or its Soviet past.

For historians and human rights activists, attempting to uncover the extent of Soviet-era repression is an uphill struggle. With archives of the intelligence services largely classified, Russians are left to create their own myths about what happened.

“The repression is still widely seen as a natural disaster,” says Yan Rachinsky of the Memorial rights organization. “There are victims, but no culprits. People are encouraged to think, ‘those were just the times.’”

This year, Memorial published the names of 40,000 people who were in the ranks of Stalin’s secret police during the height of the purges. According to Rachinsky, it is a first step towards a national reconciliation with the country’s bloody past that has so far been deliberately avoided.

“The authorities have explained away the actions of those who participated in the purges as ‘an abuse of authority,’ which is a euphemism and a mockery! Imagine Nazi criminals being judged in that way,” he says. “We need to call a spade a spade so that we can somehow move on.”

The Kremlin’s solution to the historical dilemma seems to be to avoid making any judgement on either the toppling of the Romanovs, or the Soviet regime that followed it.

At a preparatory roundtable discussion held in 2015, Medinsky, the culture minister, said the centennial would be used as an occasion to come together. “We can’t divide our forefathers into those who were wrong or right,” he said, referring to the conflict between Reds and Whites. “Both sides were clearly moved by patriotism.”

If there was a lesson to be learned from 1917, Medinsky said, it was that internal division results in “tragedy” and “leaning on the help of foreign so-called allies in domestic disputes is a mistake.”

To those listening, that statement sounded less like a lesson from the past than a lecture from the Kremlin today.

A Message from The Moscow Times:

Dear readers,

We are facing unprecedented challenges. Russia's Prosecutor General's Office has designated The Moscow Times as an "undesirable" organization, criminalizing our work and putting our staff at risk of prosecution. This follows our earlier unjust labeling as a "foreign agent."

These actions are direct attempts to silence independent journalism in Russia. The authorities claim our work "discredits the decisions of the Russian leadership." We see things differently: we strive to provide accurate, unbiased reporting on Russia.

We, the journalists of The Moscow Times, refuse to be silenced. But to continue our work, we need your help.

Your support, no matter how small, makes a world of difference. If you can, please support us monthly starting from just $2. It's quick to set up, and every contribution makes a significant impact.

By supporting The Moscow Times, you're defending open, independent journalism in the face of repression. Thank you for standing with us.

Remind me later.