Misandry: мизандрия

If misogyny is hatred or prejudice against women, what’s hatred or prejudice against men? This word is much less common in English: misandry. And how do you say “misandry” in Russian? Simple! Феминизм (feminism).

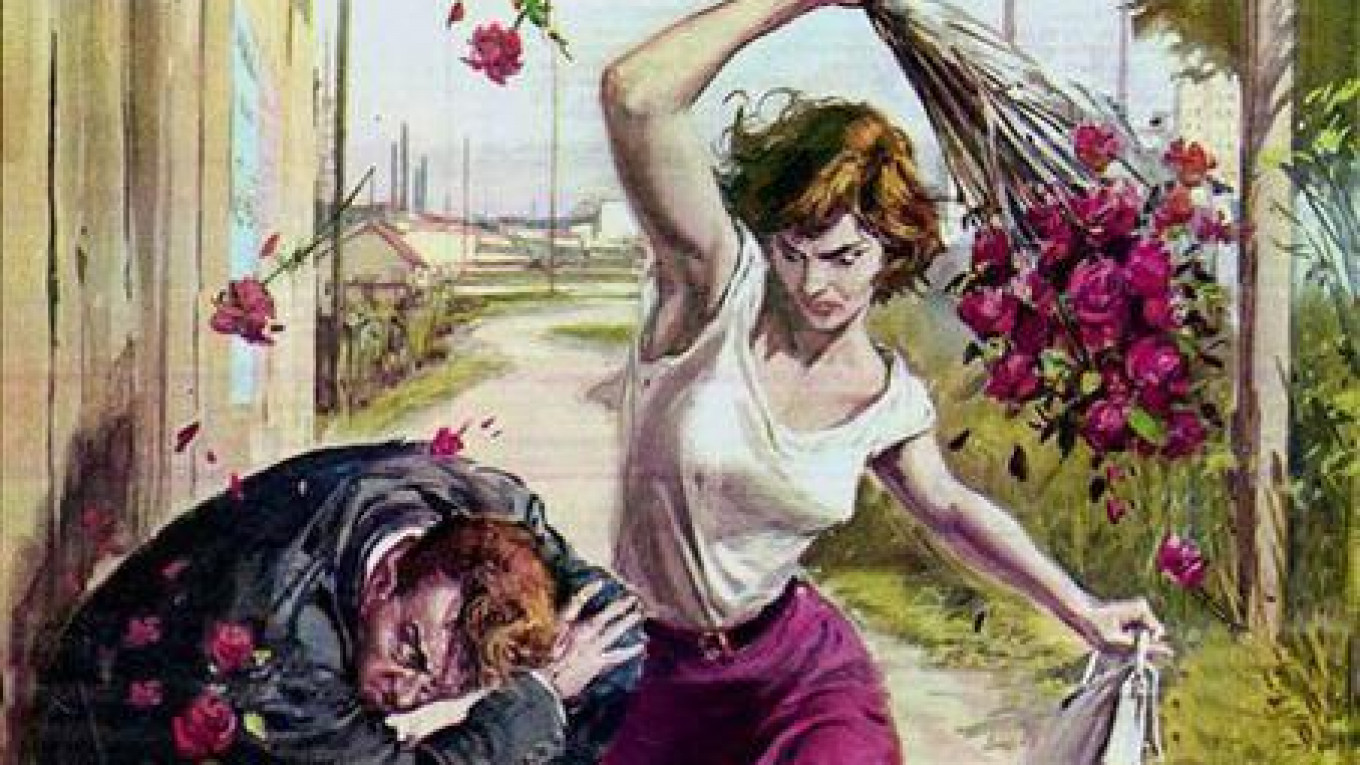

That’s a joke, folks. But as Russians like to say: В каждой шутке есть доля правды (There’s a kernel of truth in every joke). Феминизм in Russia is often associated with hatred of men rather than with the really exciting work of feminists, like lobbying for affordable childcare.

But back to hate speech, which I am still trying to master. In Russian there is an equivalent word for misandry — мизандрия. But it’s more a medical term that you’d hear it on a shrink’s couch instead of a word you’d hear around the kitchen table.

Like its counterpart мизогиния, мизандрия is better known as form of hatred: мужененавистничество (man-hating). Its practitioners are мужененавистницы (man-haters). These man-haters are women — you can tell by the –ица ending — but you also can find мужененавистники (male man-haters). On one of my favorite Russian websites where people ask questions about everything from the origin of idioms to the recipe for a sure-fire love potion, I found this query: Я мужчина и я мужененавистник. Это нормально? (I’m a man and I hate men. Is that normal?) Consensus from the opinionated public: Иди к врачу (Go see a doctor.)

But on that same fascinating site I found another kind of man-haters: plants. Yes, there are several kinds of indoor plants that Russians call мужененавистники (man-haters): Вьющееся комнатные растения — мужененавистники, чем круче растение тем хуже живется там мужчинам! (Climbing indoor plants are man-haters, and the more the plant twists, the worse it is for the men living there!)

Being called a man-hater is something women — and presumably plants — try to avoid, like this business executive: Я совсем не агрессивная феминистка и не мужененавистница (I’m really not an aggressive feminist and not a man-hater.) Apparently women have to be careful at work: Клуб мужененавистниц может стихийно образоваться (A club of man-haters can spontaneously appear). But it’s easy to spot such a club — the tip-off must be the preponderance of climbing vines on all the window sills.

But these all these man- and women-hating are, thankfully, fairly obscure forms of hatred and prejudice. More common are расисты, defined as те, кто считает кардинально другими людей другой расы (people who think other people of another race are fundamentally different).

Another garden-variety hater is националист (nationalist), although some people take pride in the moniker: Мне, как русскому националисту, за державу приятно, когда наши спортсмены выигрывают, получают золотые медали (As a Russian nationalist, I’m pleased for the state when our athletes win gold medals.) But most of the time being a nationalist puts you in bad company: Это националисты, фашисты, предатели родины, бандиты, преступники (These are nationalists, fascists, traitors, gangsters, and crooks).

Шовинисты (chauvinists) are extreme nationalists. With this word, the connotation is virtually always negative, although sometimes people pretend it’s okay: Да я шовинист, что плохого в этом? (Yes, I’m a chauvinist — what’s wrong with that?)

Then there are “phobes” — ксенофоб (xenophobe) и русофоб (Russophobe). The first is a person who fears and hates all outsiders. But the Russophobe is something else: a largely mythical creature who allegedly hates all things Russian. If you complain about Moscow’s icy streets, you’re русофоб. If you criticize the new monument of Vladimir the Great, you're русофоб. If you express concern over the Russian policy in Syria, you're русофоб. If you send out a snarky tweet about the attempts to decriminalize domestic violence in Russia, you’re русофоб.

In these cases, I just smile and say: Я не русофоб и я не феминистка. Я — мерзкая женщина. (I'm not a Russophobe and I’m not a feminist. I’m a nasty woman.)

Guaranteed to end the conversation instantly.

Michele A. Berdy is a Moscow-based translator and interpreter, author of “The Russian Word’s Worth,” a collection of her columns.

A Message from The Moscow Times:

Dear readers,

We are facing unprecedented challenges. Russia's Prosecutor General's Office has designated The Moscow Times as an "undesirable" organization, criminalizing our work and putting our staff at risk of prosecution. This follows our earlier unjust labeling as a "foreign agent."

These actions are direct attempts to silence independent journalism in Russia. The authorities claim our work "discredits the decisions of the Russian leadership." We see things differently: we strive to provide accurate, unbiased reporting on Russia.

We, the journalists of The Moscow Times, refuse to be silenced. But to continue our work, we need your help.

Your support, no matter how small, makes a world of difference. If you can, please support us monthly starting from just $2. It's quick to set up, and every contribution makes a significant impact.

By supporting The Moscow Times, you're defending open, independent journalism in the face of repression. Thank you for standing with us.

Remind me later.