The authorities have bumped up State Duma elections from December to September 2016 as nonchalantly as if they were merely doing a routine oil change on their car. It is obvious to everyone that the Kremlin administration made this decision, reasoning that the ruling authorities could achieve a stronger win in September before everyone has returned from summer vacation than in cold and gloomy December.

The shorter time frame will make it more difficult for the opposition to mount a serious campaign, and the traditionally low voter turnout in fall will work to the advantage of the authorities, who can more easily mobilize their administrative resources.

Many political analysts maintain that the ruling authorities will also benefit from the fact that half of the Duma deputies come from single-seat districts. According to the rules, such candidates are not required to state their party affiliation.

In districts where the ruling regime is unpopular, they can, for example, align themselves with the All-Russia People's Front, an organization that is not a political party and cannot take part in elections, but that serves as a convenient cover for a candidate's true affiliation with United Russia.

The Duma's so-called "opposition" parties that the Kremlin keeps in its back pocket dutifully agreed to the changes to their political life that were imposed from above, with the exception of a few "upstart" Communists who made the futile but valiant effort to shift the elections to October rather than September.

No one is particularly worried that the Constitution forbids this little shell game because it clearly states that "The Duma is elected for five years" — and one year still has 365 days, even in Russia.

Of course, that is not a problem that the Constitutional Court couldn't settle quickly with the proper interpretation of the text. But lawmakers figured, "Why bother the Constitutional Court with something so trivial?" And so they decided to shift the dates through a simple parliamentary vote.

However, officials are now offering the occasional far-fetched excuse for their hastily made changes, even though no one is asking for one. The Russian people are indifferent and no protestors are marching the streets yelling "Hands off our Duma!"

Speaker Sergei Naryshkin attempted to justify the new timing for the election by arguing that the budget for 2017 should be made by the deputies who will actually implement it. In the past, outgoing Duma deputies prepared the budget and nothing terrible happened. And besides, Duma deputies do not implement the budget. The government does — that is, unless lawmakers plan to change that also.

By comparison, federal elections in the United States have been held, without deviation, on the Tuesday following the first Monday in November ever since the 18th century. Never mind that the reason for that date has long since lost relevance — namely, to allow voters to finish the harvest, put the summer heat behind them and attend Mass on a Sunday with still enough time to reach the nearest polling station on Tuesday, even where there are no roads.

Russia, on the other hand, has probably broken all records for endlessly adjusting and modifying its electoral system over the brief 22 years of its existence. And every time, lawmakers introduced those changes in response to the political situation at that particular moment, and so as to give an advantage to those already in power.

As a result, over the last two decades, no election in Russia has been held under the same rules as the previous election cycle.

Paradoxically, on paper Russia has one of the best electoral systems in the world. It contains almost every conceivable procedure. However, the effectiveness of those procedures depends on how the laws are enforced in practice — and that largely depends on how the traditions and culture of political elections evolves over time. But how can a tradition or culture take shape if the rules are constantly changing?

In a little more than 20 years, legislators have made both major and minor changes to the laws governing elections of the president, Duma deputies and municipal authorities. Even the Duma itself has flip-flopped between using the mixed and proportional systems for electing its members.

Entry barriers ranged from 5 percent in 1993-2003 to 7 percent in 2007-2011, and will switch back to 5 percent in 2016. The number of political parties with the right to participate in federal elections has declined over time: 273 in 1995, 139 in 1999, 64 in 2003, 15 in 2007 and 7 in 2011.

There are now hundreds of registered parties, but the greatest number to clear the 5 percent barrier were the eight that did so 20 years ago. According to sources close to those who pull the electoral strings, the future Duma will host the same four parties now included, along with two or three deputies from relatively harmless opposition parties and single-seat districts.

The requirement for candidates to submit voter signatures in order to register has changed repeatedly. The line reading "against all candidates" no longer appears on ballots other than for local elections and a minimum "threshold of voter turnout" is no longer required to recognize elections as valid.

The right to form electoral blocs has been canceled. The requirements have been tightened for holding early elections and for using absentee ballots. It is easy to lose track of all the changes made to the rules and laws on election campaigns and campaign financing. It is even difficult to enumerate all of the major changes that lawmakers have introduced.

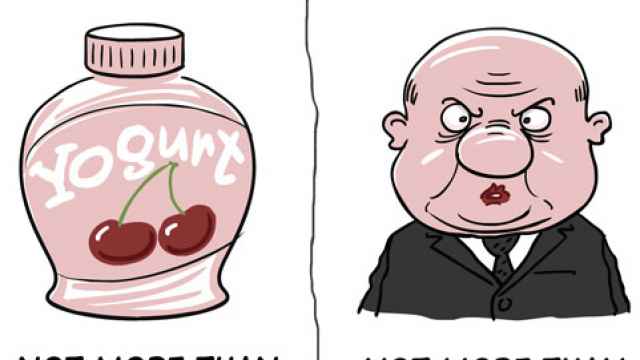

This endless meddling with the law is like a card game in which the dealer changes the rules with each new hand. It undermines the credibility of elections and prevents the formation of political traditions and practices that are no less important than the formal laws.

If only the authorities could stop messing with electoral law for 10 or 20 years and refrain from creating increasingly refined extra-legal practices for election commissions to follow, the situation might improve. But they keep molding and remolding the laws, twisting them this way and that like a pair of uncomfortable shoes that they would rather toss away completely were it not for the trace of decency stopping them.

Georgy Bovt is a political analyst.

A Message from The Moscow Times:

Dear readers,

We are facing unprecedented challenges. Russia's Prosecutor General's Office has designated The Moscow Times as an "undesirable" organization, criminalizing our work and putting our staff at risk of prosecution. This follows our earlier unjust labeling as a "foreign agent."

These actions are direct attempts to silence independent journalism in Russia. The authorities claim our work "discredits the decisions of the Russian leadership." We see things differently: we strive to provide accurate, unbiased reporting on Russia.

We, the journalists of The Moscow Times, refuse to be silenced. But to continue our work, we need your help.

Your support, no matter how small, makes a world of difference. If you can, please support us monthly starting from just $2. It's quick to set up, and every contribution makes a significant impact.

By supporting The Moscow Times, you're defending open, independent journalism in the face of repression. Thank you for standing with us.

Remind me later.