Defending the ruble has cost Russia around $80 billion this year, and depending on who's doing the calculations, its usable hard currency reserves are now either starting to run low, or at a healthy $400 billion-plus.

While Russia has only slowed the ruble's slide, it looks all right by any yardstick of whether its reserves are adequate. According to official data on Thursday, its foreign currency and gold reserves were $414.6 billion in the latest week.

While down from $509.6 billion at the end of last year, the latest total would still cover more than a year of Russian imports, far above the three-month level generally considered to be the safe minimum.

The other leading measure requires reserves at least to equal a country's external debt payments for the coming year; Russia has four times that.

Russia's currency has lost about 45 percent of its value against the U.S. dollar this year due to diving prices for oil, Russia's main export, and Western sanctions imposed over the Ukraine crisis.

But since floating the ruble last month, the Central Bank has intervened on the currency market in only relatively small amounts. Instead it has tried to slow the slide by raising interest rates by 7.5 percentage points in two takes, even though the economy has already been crushed by the sanctions and oil collapse.

Doomsayers attribute this shift to a desire to conserve what, on closer examination, may be pretty sparse reserves.

Anders Aslund, a senior fellow at the Peterson Institution Washington D.C., is one of those who say the official headline reserves figure is deceptive. That's because it includes two "rainy-day" funds built up over the years, which strictly speaking should not form part of reserves, he says.

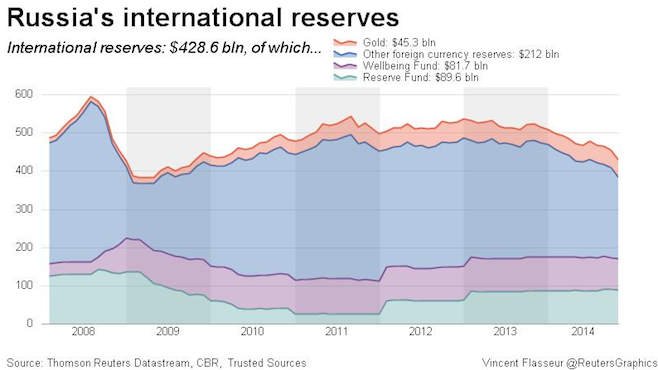

Aslund wrote this week in The Financial Times that stripping out the two funds with combined assets of $172 billion, plus gold worth $45 billion and $12 billion in International Monetary Fund drawing rights, would leave Russia with usable, or liquid, reserves of around $200 billion.

After accounting for Russia's current account surplus, which makes hard currency funds available for repaying foreign debts, the country would still have to delve rapidly into the reserves to meet its obligations.

"In each of 2015 and 2016, Russia has net external debt payments equal to $100 billion after subtracting its current account surplus. In other words Russia's liquid reserves would be finished after two years," Aslund said. "The Central Bank appears helpless because it is."

This graphic, based on data from Russia's Central Bank and consultancy Trusted Sources, shows the reserves breakdown:

President Vladimir Putin told a news conference on Thursday that the $415 billion worth of reserves was enough to cope with any crisis but would not be spent "thoughtlessly."

Officials are wary of spending the reserves too fast as the country is forecast to go into recession next year.

Without doubt, the situation is far bleaker than 2008-09 when reserves were $600 billion — well in excess of total external debt, private and public. Since then, a borrowing binge by companies has worsened the reserves-to-debt ratio.

Banks in particular — faced with weak earnings, shrinking deposits and hard currency debts — may need more Central Bank help, analysts at BNP Paribas said, estimating that the equivalent of $72 billion had already been disbursed this year.

A draft law aims to allocate an extra trillion rubles ($17 billion) to support the banking sector.

Many would argue there is nothing wrong with that, because the rainy-day money is meant for hard times such as now, when oil prices are low and companies cannot raise global capital.

More importantly, disbursing cash to the private sector from one of the two wealth funds will not entail a drop in reserves, said Citi strategist Ivan Tchakarov.

The Central Bank holds the rainy-day funds, usually in dollar assets, on behalf of the government. If the Finance Ministry wants to raid them to help a bank, the fund sells the dollars to the Central Bank in exchange for rubles.

"The overall reserves remain unchanged as what the [fund] is losing is gained by the Central Bank. The rubles that the Central Bank prints to buy the dollars are then used by the Finance Ministry to lend rubles to bank X," Tchakarov explained.

Printing currency is inflationary for the economy, Tchakarov admitted, but from a reserves point of view "there will be no change and Russian foreign reserves will remain as they were."

The question is how long the drain on reserves continues, especially if Western sanctions are extended and oil prices stay at current levels. Energy provides 70 percent of Russian export earnings and half its federal budget revenues, so at current prices Central Bank buffers are unlikely to be replenished.

Most companies are reckoned to have enough cash to fund their 2015 debt payments. Alfa Bank analyst Natalia Orlova said that even excluding the two reserve funds' assets, the remaining money would probably tide Russia over the worst of the crisis.

There is a caveat. Major changes are needed to bring more investment, diversify exports and allow Russia to reduce its dependence on energy. That seems unlikely for now.

"If you have a government that is doing reforms, the Central Bank can spend reserves. If there is no chance of structural changes happening, there is an issue because then, for the long term, $200 billion is not enough," Orlova said.

A Message from The Moscow Times:

Dear readers,

We are facing unprecedented challenges. Russia's Prosecutor General's Office has designated The Moscow Times as an "undesirable" organization, criminalizing our work and putting our staff at risk of prosecution. This follows our earlier unjust labeling as a "foreign agent."

These actions are direct attempts to silence independent journalism in Russia. The authorities claim our work "discredits the decisions of the Russian leadership." We see things differently: we strive to provide accurate, unbiased reporting on Russia.

We, the journalists of The Moscow Times, refuse to be silenced. But to continue our work, we need your help.

Your support, no matter how small, makes a world of difference. If you can, please support us monthly starting from just $2. It's quick to set up, and every contribution makes a significant impact.

By supporting The Moscow Times, you're defending open, independent journalism in the face of repression. Thank you for standing with us.

Remind me later.