MAKHACHKALA — Days after twin suicide bombings in Volgograd claimed 34 lives just ahead of the New Year, Vadim Pushkin found himself pulled off a bus travelling from Makhachkala to Moscow and interrogated by police. The officers were alarmed that Pushkin had no form of identification and was traveling out of a city known for producing suicide bombers.

To them, Pushkin's story was suspicious, to say the least: A young Russian man with no documents or possessions to speak of, and an explanation that to most would seem like a tall tale.

He was what activists call a modern-day slave, rescued days earlier from a brick factory in Makhachkala, capital of the volatile republic of Dagestan, where he had been working for more than six months with no pay and in deplorable conditions.

Pushkin is just one of more than 100 Russians that rights group Alternative says it has freed from slave labor over the past year.

When asked by police in Rostov whether anyone could verify his story, Pushkin directed investigators to Zakir Ismailov, the 30-year-old coordinator of Alternative's Dagestan branch. The group tracks down and rescues people tricked into slave labor throughout Russia — a practice the group says is frighteningly common.

Hours prior to Pushkin's detention, a journalist from The Moscow Times was present for his send-off from a bus station in Makhachkala — the same place where many of the slaves brought from Moscow are sold, according to Ismailov.

A Delicate Operation

A day after Pushkin was pulled out of the factory in the dead of night, I stand huddled with him, Ismailov and a group of drivers between buses at Makhachkala's southern station as they discuss how to get a man with no documentation out of a city that is always under scrutiny.

It won't be easy, Ismailov warns: Most surrounding regions are off-limits, having been declared counter-terror zones in light of the Volgograd bombings that took place a few days earlier.

As the bus driver and Ismailov ponder what route to take to get Vadim home without incident, a young man in a red coat glares at us menacingly from a few feet away. Ismailov says this man assists the factory owners in acquiring modern-day slaves like Vadim. He is a fixer who arranges for vulnerable or gullible people to be brought from Moscow; they get between 15,000 to 30,000 rubles per head for their effort, Ismailov says.

"The order comes from here, in Makhachkala," Ismailov says. "There is an organized group that recruits these people in Moscow and transports them back here."

Ismailov is familiar with the group he speaks of: He pulled Pushkin out of the same brick factory on the outskirts of Makhachkala from which he saved four other men weeks earlier.

The only thing Pushkin had at the time was the clothes on his back and his phone, Ismailov says, and he only worked up the courage to call for help after talking to the four men who had already been rescued.

He wound up at the factory after falling for promises of decent work and a good salary while at a Moscow train station, where such forced labor scams often begin.

They usually involve trickery and promises of solid employment, Ismailov says, or, in the worst case scenario, a cup of tea laced with a tranquilizer. The recruiters find someone who seems to be down on their luck, strike up a conversation and feign empathy, then offer a cup of tea or a shot of vodka to drown their sorrows. After that, they put him on a bus to Makhachkala, where he will be met by modern-day slave traders upon arrival.

Preying on the Vulnerable

Dozens of down-on-their-luck Russians have found themselves caught in this trap.

Andrei Popov, a young Russian conscript who went missing in 2000, shocked the public in 2011 when he resurfaced and said he had been held as a slave at several brick factories in Dagestan.

Many scoffed at Popov's explanation of his disappearance at the time and chalked it up to the young soldier attempting to avoid being charged with desertion.

A court also deemed his excuse inadequate, ruling that there was no evidence to validate his story, and in March 2012, Popov was sentenced to two years in a penal colony.

Months later, however, his story began to sound more credible.

In January 2013, 39-year-old Dmitry Sokolov from Smolensk told Komsomolskaya Pravda that he had woken up in a minibus near Dagestan after agreeing to a cup of tea with a man at Moscow's Belorussky Station.

Sokolov woke up just in time to see a man he didn't know presenting his passport to police at a checkpoint while entering Dagestan, he said. There were several other men on the bus as well, he said, and the man had taken all of their passports.

As Ismailov explained, this man was working for the factory owner, who had put out the order for workers, ensuring that his "product" got to Makhachkala safely.

"It is easy for the recruiters in Moscow to find vulnerable people," Ismailov said.

"What sort of people do they find at the train stations? People who are having trouble getting somewhere, people who are homeless, and people who are looking for work … And then it is not hard getting them to Dagestan."

Although the existence of slave labor has received considerable coverage in the Russian press, Ismailov said many people shrug it off as nonsense.

"When you explain that people in Moscow are recruiting victims and bringing them here … when you explain that to them, they just laugh. 'That can't possibly be,' they say. 'How can there be slaves in the 21st century?'"

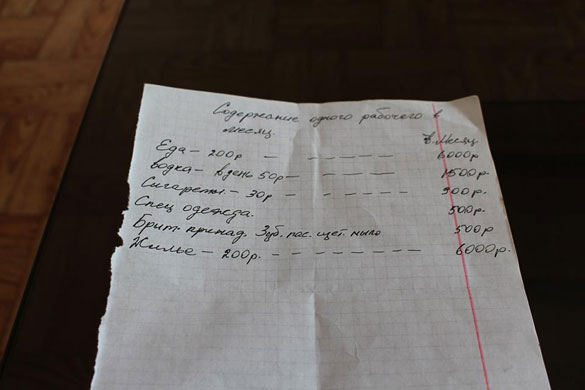

A list of expenses presented to victims of forced labor by a factory owner. The owner told them it was a legal document proving that they must pay him for everything from their uniforms to cigarettes and vodka, which he supplied them with daily.

A Broader Problem

While slave labor in Dagestan specifically has received considerable coverage by Russian media in the last year, there is reason to believe the practice is taking place in other parts of Russia as well.

Oleg Melnikov, the founder of Alternative, can testify to this. He gained prominence after breaking into a supermarket in the Moscow suburb of Golyanovo in November 2012 to free five women and four men who had been locked in a basement and allegedly enslaved for years. The victims, from Uzbekistan and Kazakhstan, reported being beaten by the store owner on a daily basis, and they were not allowed to leave the premises.

A criminal case was opened over the matter but later closed.

Although the Golyanovo case never made it to prosecution, it did feature in the U.S. State Department's 2013 Trafficking in Persons Report, an annual report that ranks countries based on the efforts they take to combat trafficking.

The report downgraded Russia from Tier 2 to Tier 3, saying the government was not doing enough to counter the problem. The report said the primary cause for concern was labor trafficking, which frequently relies on seizing passports and locking workers up. It estimated that as many as 1 million people are currently exposed to exploitative or forced labor throughout the country.

The situation in Dagestan is different, Ismailov said, in that it is easier to ignore.

Located in the turbulent North Caucasus region, Dagestan has dominated headlines in recent years for its growing Islamic insurgency, members of which are involved in almost weekly shootouts with security services. Many of the suicide bombers who have struck Russian cities in recent years came from the volatile republic.

"If it were happening in any other Russian city, Vladimir, Nizhny Novgorod … they would solve the problem quickly. But with us, no. We have more problems," Ismailov said.

"As long as people are being killed and blown up, slave labor just isn't as big of a problem — that's what people think. But it is a big problem."

In October, Melnikov went to great lengths to prove that modern-day slavery exists in Russia: He took up residence at Moscow's Kazansky Station, pretending to be a bum and acting as bait for traffickers.

Within a week, he was approached and offered a job by a man calling himself Musa, who took him to Tyoply Stan Station and handed him over to another man, Ramzan.

Melnikov said that he saw Ramzan give Musa money on the spot. When Melnikov then tried to backtrack, telling Ramzan that he had changed his mind, Ramzan suggested that the two discuss the matter over a drink.

The drink turned out to be drugged. Melnikov managed to send a text message to his colleagues from the bus he had been placed on to warn them that he was losing consciousness.

The bus was then stopped on the way to Dagestan by police who had been alerted of the situation. Melnikov spent days in a hospital recovering — he had nearly overdosed on the drug that was put in his drink.

Bus drivers who work along the Moscow-Makhachkala route said they still remember him lying unconscious in the aisle of the bus. While waiting for Pushkin's bus to leave the station in Makhachkala, one of the bus drivers reminisced about the incident, then said that he sees that sort of thing quite frequently.

According to Melnikov, Alternative has managed to raise public awareness about the problem, prompting Communist Party deputies and prominent human rights activists to push for tougher labor legislation. Now, passengers on buses from Moscow to Makhachkala have their passports checked and information recorded, complicating matters for the traffickers.

But the factory owners who put out the orders remain unfazed, Ismailov said.

When reached for comment, a man identified by Ismailov as the owner of the factory where Pushkin had been working, Ali Gamziradov, called the accusations against him "nonsense."

After first identifying himself not as Ali but as "one of Ali's relatives," and saying that he was not aware of conditions at the factory because it was being rented out, he finally admitted that he was in fact Ali.

He initially lied about his identity, he said, because he was sick of getting phone calls from people accusing him of keeping slaves.

When told that a complaint had been filed against him with police in Rostov —where Pushkin had been forced to recount his ordeal to police after being detained at a road checkpoint — Gamziradov said the complainant was "just confused."

He said that some workers had been bad seeds, known for "getting drunk at night and fighting with each other, and then destroying or stealing things," and that whoever complained about him was likely from that contingent.

Police in Dagestan were unable to provide information about the case.

According to a source familiar with the situation, the Interior Ministry's department for organized crime control and the Federal Security Service both got involved in the matter after Pushkin's detention in Rostov, and the organized crime unit conducted a raid at the Makhachkala factory. As a result of the raid, four workers who said they had been enslaved were sent home, the source said.

When contacted for comment, neither law enforcement body could provide information on the matter.

Networks of Corruption

While law enforcement appears to be paying more attention to the issue, it remains to be seen whether anyone will be prosecuted.

According to Ismailov, corruption is a complicating factor in prosecuting the factory owners, especially since most of them have relatives working in law enforcement.

Only two cases were ever successfully opened in Makhachkala, Ismailov said, and they were almost immediately closed due to a lack of evidence.

"Everyone is connected — that is the problem. It is just unheard of for any ordinary person to open up a brick factory here. He wouldn't be allowed," he said, adding that there are hundreds of factories across Dagestan.

"There was one case when we rescued a pregnant girl and her husband. We told the owner, 'We won't raise a big fuss if you pay these people.' They were each due about 25,000 rubles for their work. But he said, 'No, I won't pay them.'"

"So we went to his son, who works in the police. I tried to come to an agreement with him to pay the two. But he wouldn't — he said he didn't care," Ismailov said.

Prosecution is also impeded by the victims' reluctance to stick around for legal proceedings. The only criminal charge that can usually be proven is "illegally detaining" an individual, which carries a maximum punishment of eight years in prison. But such a charge requires the victim to act as a complainant.

Pushkin initially declined to file a complaint against his captor because he would have had to stay in Dagestan for three months. Many victims fear that if they stay, their captors might find them and punish them for leaving.

Ismailov said that he has seen this firsthand. "The people who do confront the owners about money, or ask when they'll be let go, get their teeth knocked out. They get beaten," he said.

"I asked Vadim why he didn't just confront the owner and demand the money. He said, 'What's the point? Then they'd just bury me somewhere out here,'" Ismailov said.

At the same time, many of the victims stay not because they are chained up or physically detained, but because they are so terrified of leaving. "They detain them morally, psychologically, not physically. They break them," Ismailov said.

Most of the time, the rescue operation is equally subtle.

"To rescue someone, we usually spend an entire week just observing the factory learning about the factory owners, and finding out if there's security. We talk to the slaves and find out how many are in there who need to be rescued. We have to do it all as safely and cautiously as possible," Ismailov said.

"If we just went and broke doors down and demanded that they give up the people — it wouldn't work."

Too Late for Some

In some cases, victims of forced labor are found when it's already too late to help them.

Lutfillo Ishankulov, an Uzbek laborer who said he had been enslaved in Dagestan after a man in Moscow promised him a decent, well-paying job, was found unconscious on the side of a road in Makhachkala last spring.

After being taken to a local hospital, doctors determined that he had been severely beaten and had developed "a whole multitude of illnesses."

Volunteers from Alternative gathered as much money as they could in donations to pay for Ishankulov's medical treatment, but he ultimately died within weeks, Ismailov said, showing a photograph he had taken at the hospital moments before Ishankulov's passing.

According to Ismailov, Ishankulov had developed a problem with his kidney, but when his bosses at the factory realized he was too sick to work, they dumped him on the side of the road with no documents instead of taking him to a hospital.

"His own family didn't come to say goodbye," Ismailov said. "They said they were afraid they would wind up in some basement too."

Contact the author at [email protected]

A Message from The Moscow Times:

Dear readers,

We are facing unprecedented challenges. Russia's Prosecutor General's Office has designated The Moscow Times as an "undesirable" organization, criminalizing our work and putting our staff at risk of prosecution. This follows our earlier unjust labeling as a "foreign agent."

These actions are direct attempts to silence independent journalism in Russia. The authorities claim our work "discredits the decisions of the Russian leadership." We see things differently: we strive to provide accurate, unbiased reporting on Russia.

We, the journalists of The Moscow Times, refuse to be silenced. But to continue our work, we need your help.

Your support, no matter how small, makes a world of difference. If you can, please support us monthly starting from just $2. It's quick to set up, and every contribution makes a significant impact.

By supporting The Moscow Times, you're defending open, independent journalism in the face of repression. Thank you for standing with us.

Remind me later.