The four wild boars that wandered into Krylatskoye on the city’s western flank not long ago were bearing a message: Something is not right with the Moscow region’s woods.

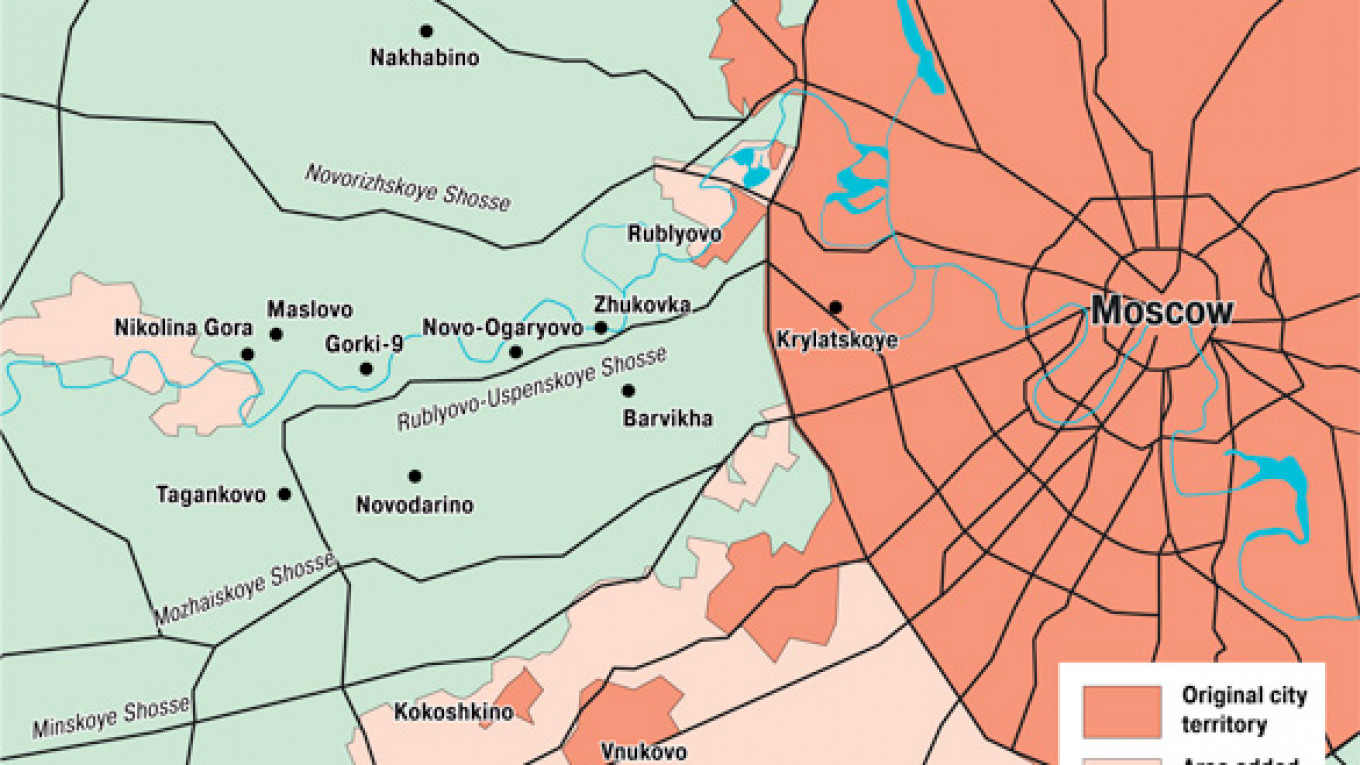

Local environmental officials interpreted the animals’ flight toward the city late last month as further proof that the once dense forest areas off Rublyovo-Uspenskoe Shosse are shrinking as developers manipulate zoning rules, level forests and build luxury properties on Russia’s most expensive real estate.

Rublyovka, a vaguely defined zone of pine and birch woods extending along a highway that skirts the south bank of the Moscow River in the Odintsovo district of the region, has over the past two decades become synonymous with wealth, power and garish mansions lurking behind high fences and closed-circuit television cameras.

And the irony is not lost on those who know local history: Leonid Brezhnev himself was fond of strolling out the door of one of the many government dachas in the area to hunt boar in the very woods that are now disappearing because of the concentration of power and wealth.

But now, this unique district could become the venue for the latest showdown over the Moscow region’s forests.

Environmentalists, politicians and residents of one of the most prestigious dacha communities have recently banded together to try to stop corrupt officials and unscrupulous businessmen who they say are involved in a mass looting of woodlands.

The Paper Trail

Between March and May, activists claim that anywhere from 500 to 1,500 hectares of official forestland in the Moscow region — the vast majority in Rublyovka — was reclassified as “residential land” attached to communities it bordered, under orders signed by outgoing governor Boris Gromov.

On paper, that is perfectly legal. But activists say the transfers took place without required public consultations, and have resulted in the possibility of building on the territory, which was essentially impossible while it was protected by its status as being part of the forest fund.

The scheme, they say, is simple. After the land is reclassified as fit for habitation, offshore companies lease plots from the regional government at a token price and then begin to clear trees in order to build on them.

This latest method follows a long and sordid history of pseudo-auctions for legitimately renting woods, in which powerful people would get chunks of land next to their homes for a song.

“We’re talking about places like Zhukovka, Barvikha, Gorky, and they are ‘renting’ it for the absolute minimum price, maybe 5,000 rubles ($154) per hundred square meters. Can you imagine?” said Oleg Mitvol, a former deputy head of the state environmental watchdog Rosprirodnadzor and the founder of Green Alternative, a new political party.

To get an idea of Mitvol’s incredulity, it is worth revisiting the apocryphal stories the district has given rise to.

This is a district where in the toiletries sections of supermarkets one can find gold-headed toothbrushes retailing for 5,000 rubles, and then stop next door to pick up the latest model of Maserati. Businessmen defending their alleged incomes have even been heard to use their lack of a house on Rubylovka as evidence of their incorruptibility.

A Matter of Prestige

The area has been favored by government officials since Soviet times, but the property boom started after President Vladimir Putin moved into his Novo-Ogarevo residence in Usovo, a settlement on Rublyovo-Uspenskoe Shosse, during his first presidential term in the early 2000s.

Dmitry Medvedev moved into the luxuriously refurbished former dacha of Boris Yeltsin, about 6 kilometers down the road from Putin in Gorki-2, after he was inaugurated as president in 2008.

While not the best of neighbors — the two-lane Rublyovo-Uspenskoe Shosse is regularly closed to other traffic while the leaders or their visitors are whisked to and from the center in motorcades, resulting in massive jams and abusive comments on Yandex.probki — the district remains the residence of choice for the rich, famous and connected.

But as addresses along Rublyovo- Uspenskoye Shosse proper have been snapped up, developers have begun to cast the net wider – with obvious consequences for the local trees.

“Basically, along Rublyovka you have prestigious old dacha communities, and then you have newly built homes. But it became so popular in recent years that the land between Rublyovo-Uspenskoe Shosse and Novorizhskoye Shosse to the north has now become the focus of construction,” explained Anton Beneslavsky, head of Greenpeace Russia’s Boreal Forest Campaign.

That pressure was what the recent forest grab was all about, said Beneslavsky.

Real estate prices in the area peaked just prior to the 2008 crisis, with a hundred square meters of Rublyovka land selling for between $30,000 and $100,000 depending on proximity to the city, water and, no less importantly, trees.

In those halcyon days, the land here was so valuable that to control it people were prepared to resort to violence — and even to kill.

In 2007, Valery Yakovlev, a former local government official in charge of property sales in the Odintsovo district, was blown up as he drove his Lexus down Rublyovo-Uspenskoye Shosse, apparently because of his influence over the area’s lucrative local real estate market.

Today, property prices are climbing back to their pre-crisis levels, though no one has apparently been killed over it recently.

But environmentalists maintain that corrupt officials pulled off this spring’s massive land grab, and they are demanding an investigation, which newly appointed Governor Sergei Shoigu ordered.

“We are not planning on giving up forest plots in order to build low-rise housing,” Moscow region official Andrei Sharov told Vedomosti last month, referring to an alleged plan by Gromov. “And instead we are going to expand the amount of woods.”

Tricky Mice

There are other methods available to take over woodlands, said Mitvol: Maps can be redrawn to classify forestland as burnt or otherwise useless, which is used as an excuse to transfer it to a beneficiary. Or, alternatively, the unscrupulous can bribe officials to classify their developments on forestland as nonpermanent dwellings, which are allowed in certain cases under the forest code.

One particularly remarkable machination was used near Nikolina Gora, an old dacha community founded in the 1920s for the Soviet Union’s scientific and artistic aristocracy, whose residents today include filmmaker and staunch Putin supporter Nikita Mikhalkov.

The official plan of the area had been conveniently “eaten by mice,” and back-up copies lost in a fire, and when the document was finally resurrected, about 20 hectares of what were woods had become private property, Mitvol said.

However, the outcome, he said, is the same: the mass deforestation of the region for building lucrative real estate.

Confused record keeping and constant redrawing of boundaries make it impossible to estimate the actual rate of loss of woodland in the area in recent years, said Beneslavsky.

Now some of the area’s most prestigious residents, fed up with seeing their woods flattened, have joined the fray.

In an open letter to Putin published in last Thursday’s Kommersant, several prominent residents of Nikolina Gora — including opera singer Yevgeny Nesterenko, journalist Andrei Karaulov, host of the long-running “Moment of Truth” news program, and five people’s artists of the Soviet Union — appealed to the president “as a guarantor of the Constitution and as a man” to halt the clearance of woodland around the nearby villages Maslovo and Chesnokovo.

The letter writers complain that 250 hectares of the 1,000-hectare forest are being privatized by unidentified “dealers, various traders and unscrupulous authorities” with a view to profiting from development there.

“With the help of loopholes in legislation under the guise of leases, they have already removed more than 250 hectares from the forest fund and are now registering it as the property of various businesses with the aim of a future resale and transfer of the received profits to offshore accounts abroad,” the writers said.

The Natural Resources and Environment Ministry has confirmed the claim by environmentalists about the flurry of reclassifications at the end of Gromov’s reign. Plots ranging in size from 6.7 to 118 hectares ceased being woods and became property attached to a variety of settlements, including Maslovo, Novodarino and Tagankova.

The ministry opened an investigation into the transfers last month. In a statement released Tuesday, it said its inquiries so far had found no evidence of wrongdoing. But it named seven plots of land, five that were incorporated on May 5 into Zhukovka on Rublyovo-Uspenskoe, and two near Nakhabino, on Volokolamskoe Shosse (which runs to the north of Novorizhskoye Shosse), that required “additional checks.”

Neither Mitvol nor Beneslavsky, who said he had handed materials detailing the corrupt scheme to investigators, was prepared to name the individuals he believes are behind the schemes while the investigation is in progress.

According to the ministry’s statement, however, requests to reclassify the five plots near Zhukovka came from Sergei Sobko, the Communist chairman of the State Duma’s industry committee, who signed himself as general director of four companies called Kashtan, Khvoiny, Dubrava and Kedr (all of which, appropriately, are named for various trees), and one Irina Simakhina, general director of a company called Landshaft-3.

The two plots near Nakhabino were apparently rented by two companies called Akvilon and Trinidad.

Sobko threatened to sue the Izvestia newspaper when it first published allegations about his companies’ purchase of the land Gromov extracted from the forest fund last month. The article is no longer accessible on the Izvestia website.

One signatory of the letter about the nefarious doings near Nikolina Gora that was printed in Kommersant denied having anything to do with it.

None of the other alleged signatories were available for comment.

Environmentalists have expressed some hope that new governor Sergei Shoigu could be sympathetic to the cause. He has backed ecowarriors at Zhukovsky, on the eastern side of the city, who have campaigned against forest clearing for developments around the air base there.

On July 1, his new administration took control of the region’s forests from the Federal Forest Agency. The Moscow region was until this time the only Russian region not to administer its own forests.

“Right now we are seeing a real shift in policy; if he sticks to the course he has started on, it is good news,” Beneslavsky said.

But new housing and commercial property are not the only threats to the area. The federal government is considering building a new headquarters for the presidential administration at the end of Rublyovo-Uspenskoe Shosse and a new 37-kilometer road linking that spot to the Moscow Ring Road is already under construction to service it.

As a result, residents of the western part of the city could be seeing more wild pigs seeking refuge in the future.

A Message from The Moscow Times:

Dear readers,

We are facing unprecedented challenges. Russia's Prosecutor General's Office has designated The Moscow Times as an "undesirable" organization, criminalizing our work and putting our staff at risk of prosecution. This follows our earlier unjust labeling as a "foreign agent."

These actions are direct attempts to silence independent journalism in Russia. The authorities claim our work "discredits the decisions of the Russian leadership." We see things differently: we strive to provide accurate, unbiased reporting on Russia.

We, the journalists of The Moscow Times, refuse to be silenced. But to continue our work, we need your help.

Your support, no matter how small, makes a world of difference. If you can, please support us monthly starting from just $2. It's quick to set up, and every contribution makes a significant impact.

By supporting The Moscow Times, you're defending open, independent journalism in the face of repression. Thank you for standing with us.

Remind me later.