There’s an old Soviet joke: A factory worker puts a down payment on a Zaporozhets, a ramshackle Ukrainian Fiat knockoff with an engine in the rear, a removable floor panel for ice fishing, and a tendency to go up in smoke at the first sign of breaking 80 kilometers an hour. The official from the planning office tells him that the car will be ready exactly five years from today’s date. “Is it going to be ready in the morning, or the afternoon?” the worker worries. “Why on earth do you want to know that?” replies the official, bemused. “Because the plumber’s coming in the morning!”

Soviet consumerism’s weird centrally planned world — sometimes ingenious, sometimes horrific, always idiosyncratic — is the subject of “Made in Russia,” an excellent new pocket guide to an era before every Moscow apartment was yevroremont and everything in it came from IKEA. With wry, snarky commentary from Bela Shayevich and personal essays from emigre writers like Gary Shteyngart, the book catalogs 50 exemplars of a style its editor Michael Idov coins as “Soviet magpie modernism.” Roughly speaking, this entails the industrial design boom that followed the “kitchen debates” between Nixon and Khrushchev at a 1958 Moscow trade expo when, challenged on the relative merits of capitalist color television and Communist rocket launches, the Soviet premier threw down the gauntlet: “Let us compete. The system that will give the people more goods will be the better system, and victorious.”

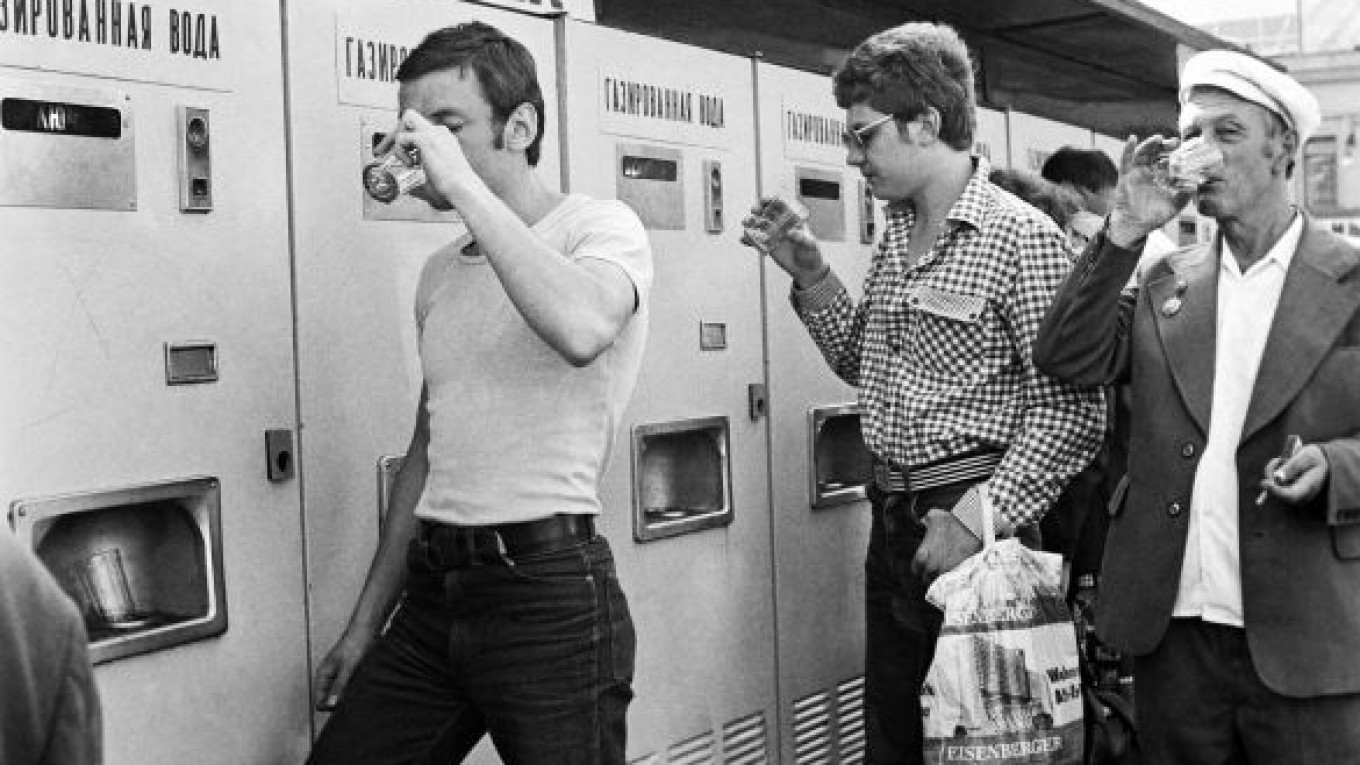

While we all know how that turned out, “Made in Russia” does a considerable service in rejoining the grayscale view many have of the Soviet Union. Khrushchev’s obsession with matching and beating Western quality-of-life standards led to the creation of VNIITE, a “technical aesthetics research institute” devoted to the hitherto unknown concept of industrial design. Offered considerable leeway for the time — they were allowed to subscribe to foreign periodicals and compete in design competitions abroad — armies of designers set about copying whatever goods made it through the Iron Curtain. Most of the results are a far cry from the MIT Media Lab, to put it mildly. They include a collapsible drinking cup, devised to avoid hygienic issues from shared cups at communal soda fountains; a fire-hazard radiator with an exposed heating coil; a portable “boiling wand” used to replace tea kettles; and, of course, the Zaporozhets, a clunker as ridiculed in its day as it is now.

Perhaps the greatest problem Soviet designers encountered lay in marrying the dream of a utopian consumer paradise with the prosaic functions their creations were meant to have. Many products took their name and form from major Soviet space exploration programs and construction projects, a phenomenon the artist Vitaly Komar calls “science fiction feeding back into life” in one of the book’s essays. Disparities between the two were frequently stark. The Aelita blowdryer, hot enough to singe hair, was named after an avant-garde film involving a socialist revolution on Mars; Belomorkanal cigarettes — capable of turning lungs into peat bogs — were inspired by the building of the White Sea Canal in 1931, one of the major engineering triumphs of the First Five-Year Plan.

This paradoxical disconnect between a brand and the product’s functionality stemmed from the absence of competition between Soviet manufacturers: There was no market-driven incentive for factory bosses to make better goods as long as their current product did not break. Even VNIITE’s not infrequent triumphs could never be translated into mass-produced goods. Dmitry Azrikan, the U.S.S.R.’s star designer in the 1960s, once won a competition to design a new taxi cab for New York City. But his superiors did nothing save patting him on the back, and the project fell by the wayside.

It was no surprise, then, that the Soviet design revolution died quickly and quietly once goods from countries with better conveyor-belts — think the Indian jeans and Vietnamese watches immortalized in Leonid Parfyonov’s “Namedni” series — began to flood into the country in the 1980s. And Russian design is still long overdue a renaissance, as anyone who has been to a government building or seen public interest posters in the metro knows.

That may be why several of the objects here are fondly remembered and genuinely missed. The last decade saw mobile kvas barrels — a curious precursor to the food truck, they carry a brownish, lukewarm soda-like drink made from rye bread and dispensed by frumpy old dames — return to Russia’s streets. Even IKEA has taken notice: The Swedish design giant now makes a beveled glass almost identical to the ubiquitous one designed by socialist realist Vera Mukhina — with “Made in Russia” emblazoned on the bottom.

Made in Russia: Unsung Icons of Soviet Design. Editor: Michael Idov. 224 pages.Rizzoli $25.

A Message from The Moscow Times:

Dear readers,

We are facing unprecedented challenges. Russia's Prosecutor General's Office has designated The Moscow Times as an "undesirable" organization, criminalizing our work and putting our staff at risk of prosecution. This follows our earlier unjust labeling as a "foreign agent."

These actions are direct attempts to silence independent journalism in Russia. The authorities claim our work "discredits the decisions of the Russian leadership." We see things differently: we strive to provide accurate, unbiased reporting on Russia.

We, the journalists of The Moscow Times, refuse to be silenced. But to continue our work, we need your help.

Your support, no matter how small, makes a world of difference. If you can, please support us monthly starting from just $2. It's quick to set up, and every contribution makes a significant impact.

By supporting The Moscow Times, you're defending open, independent journalism in the face of repression. Thank you for standing with us.

Remind me later.