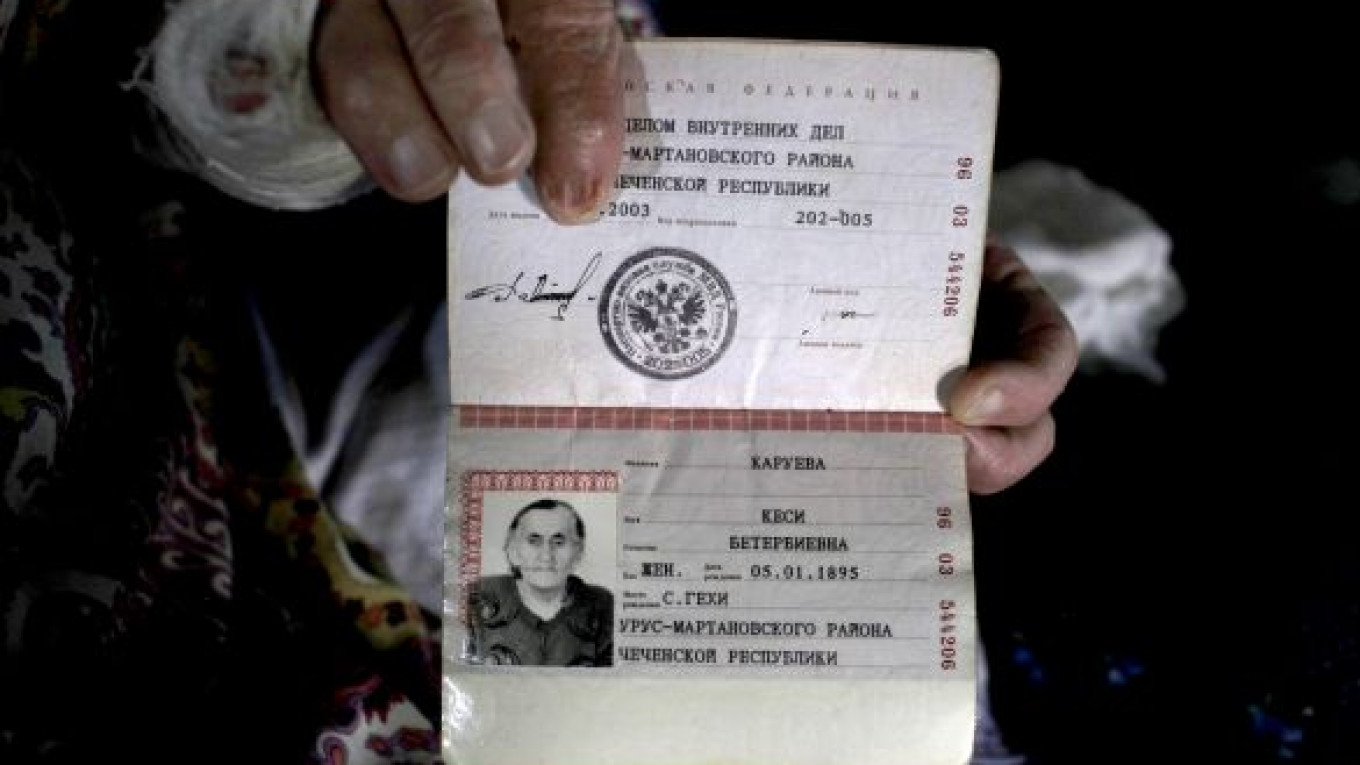

GOITY, Chechnya — A black hijab frames the heavily wrinkled face of Kesi Karuyeva, a great-grandmother from Chechnya whose official documents appear to show she is the oldest person in the world.

Having lived through the Bolshevik Revolution almost a century ago, the enforced deportation of Chechens at the hands of Josef Stalin and two post-Soviet separatist wars, Karuyeva's passport says she turned 116 at the start of this year.

Though the claim could not be independently verified, it would make the Chechen villager a year older than American Besse Cooper, who was named the world's oldest living person by Guinness World Records earlier this year.

"My father was very rich but when [Tsar] Nicolas' rule ended, the money was tossed away," Karuyeva said of the 1917 Revolution, when Communists swept to power, forcefully seizing private property.

Relatives of Karuyeva who live with her in the tiny village of Goity some 20 kilometers south of the regional capital, Grozny, say her memory is flawless.

"She's just a little deaf, that's all. Life was not sweet for her, it was very hard," relative Leila Karuyeva said in their modest brick house, where jars of pickled tomatoes and peppers rest beside Muslim prayer beads on the windowsill.

The gray eyes of the hunchbacked supercentenarian tear up as she recalls the plight of her people when Soviet dictator Stalin deported the entire nation in 1944 to Central Asia after accusing them of collaborating with invading Nazi Germany.

"We were loaded into big trucks, and the Russians pointed at us with guns. We weren't allowed to move to either side, weren't allowed to go to the toilet," Karuyeva said in her native Chechen, gesturing a gun with her arm and fingers.

Many of the Chechens died. Karuyeva was sent to Ridder, a small barren town in the east of Kazakhstan, where she said she buried her husband and eight of her 10 children.

"It was so cold there. I remember my legs freezing, and my daughter couldn't pull my icy legs from my frozen boots," she said, choking back a tear.

Soviet leader Nikita Krushchev let deported Chechens return home in 1957.

The scars from the brutal upheaval of an entire nation remain today — it planted the seed of separatism that is cited by Islamist rebels today who are fighting for a separate state across the North Caucasus.

"Life is a little better now," said Karuyeva's daughter, Khazan, a 76-year-old who sat opposite her mother.

A Message from The Moscow Times:

Dear readers,

We are facing unprecedented challenges. Russia's Prosecutor General's Office has designated The Moscow Times as an "undesirable" organization, criminalizing our work and putting our staff at risk of prosecution. This follows our earlier unjust labeling as a "foreign agent."

These actions are direct attempts to silence independent journalism in Russia. The authorities claim our work "discredits the decisions of the Russian leadership." We see things differently: we strive to provide accurate, unbiased reporting on Russia.

We, the journalists of The Moscow Times, refuse to be silenced. But to continue our work, we need your help.

Your support, no matter how small, makes a world of difference. If you can, please support us monthly starting from just $2. It's quick to set up, and every contribution makes a significant impact.

By supporting The Moscow Times, you're defending open, independent journalism in the face of repression. Thank you for standing with us.

Remind me later.