Around the globe, there is a heated discussion among policymakers, bankers and analysts about the role of the major credit ratings agencies. This discussion was provoked after we witnessed their incompetence in rating collateralized instruments in the early 2000s. According to the U.S. Financial Crisis Inquiry Commission 2011 report, they were “key enablers of the financial meltdown” in 2007 and 2008. The discussion has been reignited recently by Standard & Poor’s decision to downgrade the U.S. credit rating.

Notably, global investors reacted to the downgrade by piling into U.S. Treasuries. But it did provide an opportunity for the Finance Ministry to enter the debate, criticizing the agencies for giving Russia low ratings. It said boosting the rating to the A level is a government priority, undoubtedly driven by Prime Minister Vladimir Putin’s comments on July 13 that giving Russia such a low rating is an “outrage.”

In my opinion, a country where 60 percent of the state budget is dependent on natural resource prices cannot be upgraded until this dependence is reduced to an acceptable level.

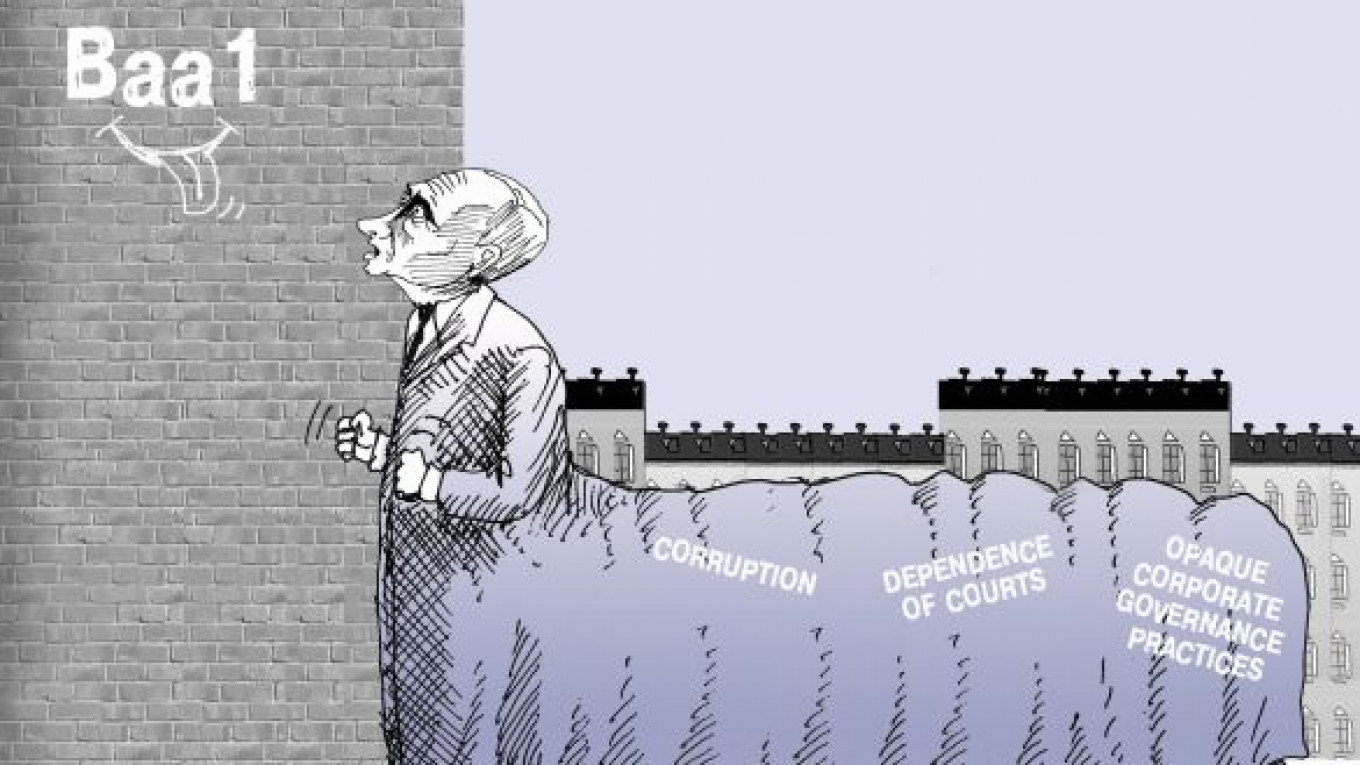

Fitch has rated Russia as BBB with a positive outlook, S&P is at BBB with a stable outlook, and Moody’s rates the country Baa1 with a stable outlook. These subprime ratings make it harder and more expensive for the government to borrow.

Moreover, as we have seen in the euro zone, concern about the government’s credit worthiness also has an impact on the credit worthiness of domestic banks that hold significant amounts of government debt on their balance sheets, making it more expensive for them to borrow as well.

The cost of borrowing will be a critical issue for the government in the next 2 1/2 years, when it will try to keep the budget deficit to a minimum. The Finance Ministry’s plan for new debt issuances in 2012-14 was approved on Aug. 11, amounting to more than 2 trillion rubles ($70 billion) annually in domestic sovereign debt and an additional 200 billion rubles annually in new foreign debt.

This new issuance is partially the result of lower oil prices. In 2010, the deficit amounted to 3.9 percent of gross domestic product, and the government forecasts the shortfall will decline to 3.6 percent this year. The draft budget plan for 2012-14 that is currently being finalized by the Cabinet is based on an assumption that the average price of Urals crude oil will remain $93 to $97 per barrel, resulting in a federal budget deficit of 2.3 percent to 2.7 percent of GDP annually. The Finance Ministry added that crude prices would have to average $125 per barrel over the period for the budget to balance.

This, of course, is much below the budget deficits in the United States and Europe, which is the reason why the Finance Ministry argues that Russia should be rerated, aided by the debt-to-GDP ratio of only 9.3 percent. Even on the new debt issuance plan, the ratio will rise to just 17 percent by the end of 2014.

Another argument in favor of rerating is that Russia is running a significant trade surplus, amounting to $17.4 billion in June alone, according to data released on Aug. 10.

The Moscow Times in its Aug. 10 editorial titled “Russia and U.S. Find a Foe in S&P” wrote: “Despite glowing numbers presented in the new Finance Ministry report, the government has failed to lower the risk level of the country’s investment environment by allowing corruption to flourish, doing little to guarantee the independence of the courts, and stubbornly adhering to opaque governance practices that, among other things, have left investors wondering who will run in the presidential election less than seven months away.” Given my own personal experience and the highly politicized and illegal takeover of the Bank of Moscow by VTB, I could not agree more.

While Putin bemoans the country’s credit rating as an outrage, it is the politicians and the flawed system that are largely causing the problems.

Judging by the reaction to the downgrade of the United States, international investors would probably pay little attention to an upgrading of Russia. What they would pay attention to would be a free and fair election of a leader who can institute international standards of corporate governance, transparency and freedom of speech.

Instituting an independent judiciary and rule of law could be the most powerful catalyst to revive faith in the credit worthiness of Russia as a haven for foreign investment.

Andrei Borodin, the founder of Bank of Moscow, served as its CEO from 1995 to 2011.

A Message from The Moscow Times:

Dear readers,

We are facing unprecedented challenges. Russia's Prosecutor General's Office has designated The Moscow Times as an "undesirable" organization, criminalizing our work and putting our staff at risk of prosecution. This follows our earlier unjust labeling as a "foreign agent."

These actions are direct attempts to silence independent journalism in Russia. The authorities claim our work "discredits the decisions of the Russian leadership." We see things differently: we strive to provide accurate, unbiased reporting on Russia.

We, the journalists of The Moscow Times, refuse to be silenced. But to continue our work, we need your help.

Your support, no matter how small, makes a world of difference. If you can, please support us monthly starting from just $2. It's quick to set up, and every contribution makes a significant impact.

By supporting The Moscow Times, you're defending open, independent journalism in the face of repression. Thank you for standing with us.

Remind me later.