The brutal beating of Kommersant reporter Oleg Kashin has outraged the professional community and human rights activists. Signatures are being gathered for an appeal to President Dmitry Medvedev calling for an investigation into this and a host of other crimes against journalists.

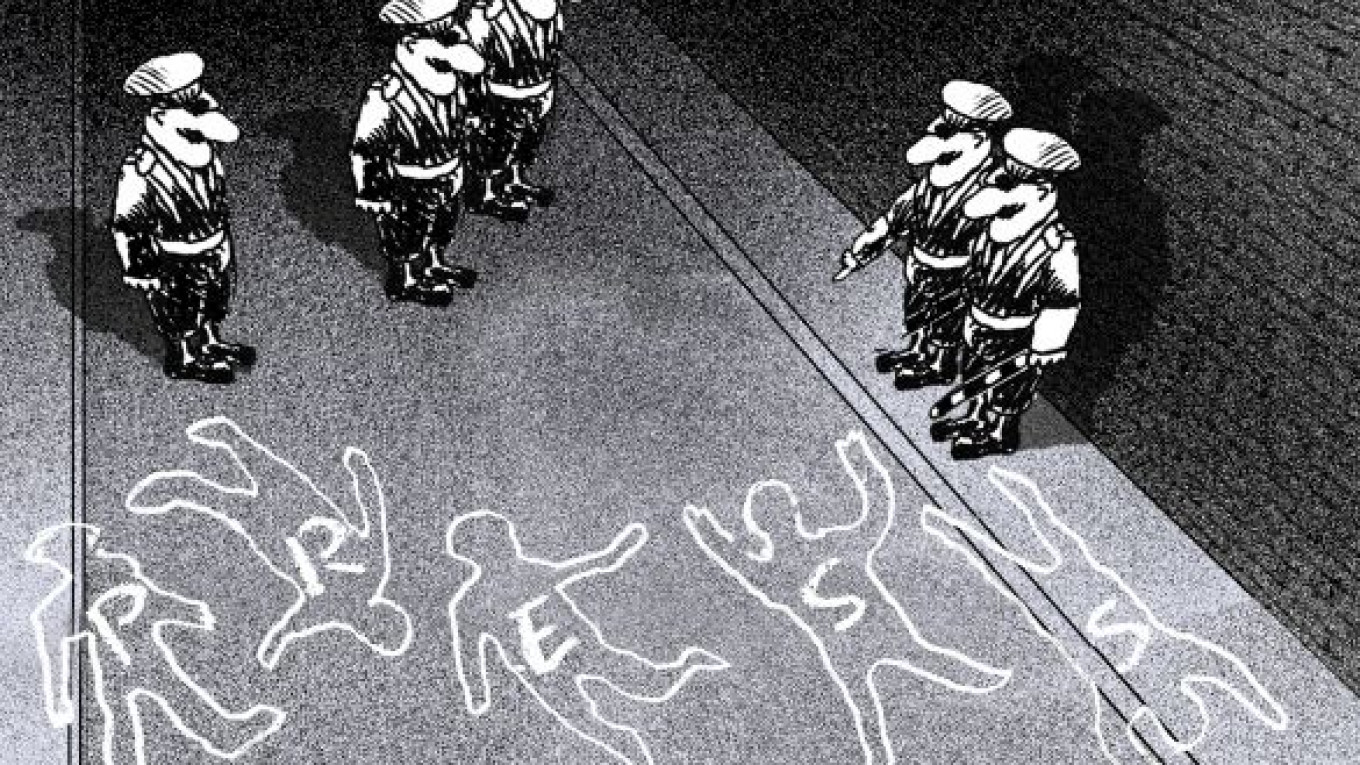

The goal is to make the authorities enforce Article 144 of the Criminal Code, which makes it a crime to obstruct a journalist’s professional work. The authors of the appeal point out that the murders of Vladislav Listyev, the former head of ORT television, precursor to Channel One, and Novaya Gazeta journalist Anna Politkovskaya, as well as the savage attack on Khimki journalist Mikhail Beketov, have not been solved. In fact, eight journalists have been killed and 40 attacked this year alone.

The president has already ordered Prosecutor General Yury Chaika and Interior Minister Rashid Nurgaliyev to oversee the investigation personally. Unfortunately, in many similar cases, oversight by the top officials has led nowhere. Just the same, we hope that with the order coming directly from the president, a timely and thorough investigation will be conducted. Of course, a long wait under the present circumstances would be difficult.

The numerous attacks and killings have established a pattern defining journalists’ relationship with the public and the state in contemporary Russia.

The Russian media have long ceased to be regarded as the Fourth Estate. Both the professional community and the state itself are equally at fault for the fact that society holds journalists in such low regard. Much of the media is controlled by the state, blunting economic incentives and preventing the development of a market for independent media. Legal and judicial barriers such as the loosely worded law on extremism severely limit journalists in their activities. The understanding that journalists fulfill a vital function beneficial to the state has yet to take root in Russian society. In this regard, nobody ever recalls that the law on mass media contains a clause providing guarantees to journalists as professionals performing a public duty. The professional community should lobby for legislation that would equate attacks against journalists as attacks on the state, making it the same crime as attacking senior officials, State Duma deputies or judges.

The people who order these beatings and murders bear a deep grudge against journalists for what they have published, and they are convinced that violence is the most appropriate method to “solve the problem.”

Perhaps this is because of the common misconception that journalists are all biased, which explains why the perpetrators view the elimination of journalists as the eradication of foes. After all, in their view, war is war. Since receiving the official green light to hold power in government and business, 1990s-era bandits have retained the same familiar methods in their new jobs, and the undermining of mass media’s standing in society is a logical outcome.

The mass media are a means for society to monitor itself — including the authorities and the business community. But in Russia that system of oversight is ineffective. Freedom of speech exists, but the media have no influence as an institution.

Press reports do not necessarily lead to the punishment of wrongdoers or the overturning of unjust rulings. But those reports can result in the murder, beating or discrediting of their authors. Maybe these are acts of vengeance against journalists for having spoken the truth. If so, that means the question of reputation does matter in Russia.

But that would mean that law enforcement bodies, which do not solve these crimes against journalists, do not care about their own reputation. Otherwise, the state is either intentionally concealing the identity of the offenders, or else the system itself is so ineffective that it cannot control its own actions, much less those of the criminals.

The limp reaction from the professional community to previous attacks on journalists has further contributed to the impunity of the perpetrators. The distorted view of competition among the media, the dominance of state-controlled media, and the resulting lower standards and expectations of the public have led to a dearth of serious investigative journalism and the inability of independent media outlets to band together for concerted action. The letter to the president and demonstrations in front of the Interior Ministry are good steps, but they alone are not enough. The influence and standing of Russia’s Fourth Estate would increase if it were to conduct joint investigations into the most important issues, simultaneously publish their findings and coordinate lobbying efforts for better legislation. Like scattered soldiers confronting a common foe, it is time they unite. War is war.

This comment appeared as an editorial in Vedomosti.

A Message from The Moscow Times:

Dear readers,

We are facing unprecedented challenges. Russia's Prosecutor General's Office has designated The Moscow Times as an "undesirable" organization, criminalizing our work and putting our staff at risk of prosecution. This follows our earlier unjust labeling as a "foreign agent."

These actions are direct attempts to silence independent journalism in Russia. The authorities claim our work "discredits the decisions of the Russian leadership." We see things differently: we strive to provide accurate, unbiased reporting on Russia.

We, the journalists of The Moscow Times, refuse to be silenced. But to continue our work, we need your help.

Your support, no matter how small, makes a world of difference. If you can, please support us monthly starting from just $2. It's quick to set up, and every contribution makes a significant impact.

By supporting The Moscow Times, you're defending open, independent journalism in the face of repression. Thank you for standing with us.

Remind me later.