As we wait for Russia to respond to the announcement last month of new U.S.-Japan defense guidelines, it seems that Russia-Japan relations have come to a crossroads.

The guidelines, which set the objectives and scope of U.S.-Japan defense cooperation, are the most expansive in history, with Japan now expected to play a more active role in supporting U.S.-led operations around the globe. They also put significant emphasis on upgrading cooperation between Japan and the U.S. on ballistic missile defense, or BMD.

Don't be surprised if those three letters begin creeping back into the news. The BMD issue helped crash the U.S.-Russia reset back in 2009, when plans to deploy BMD hardware in Poland and the Czech Republic were seen by Russia as a threat to its strategic deterrent. Now, the announcement of deepening cooperation on BMD between the U.S. and Japan offers a similar card — but will Russia choose to play it?

There are reasons to think Russia might take a lower profile on the issue this time around. First, Northeast Asia is no Europe: the potential for full-scale conflict is greater, with territorial disputes and historical tensions posing a constant challenge to attempts at greater integration.

Second, Russian and U.S. interests do not collide in the region as fundamentally as they do in Europe: For the last two decades, Russia has tolerated, and even expressed appreciation for the stabilizing role the U.S.-Japan alliance plays in the region.

And third, Russia has sought to improve relations with Japan, to hedge against excessive reliance on any one partner in the region.

Russia-Japan relations don't tend to make the headlines all that often. The defining issue of their relations up until very recently has been a dispute centering on sovereignty over the four southernmost islands of the Kuril Archipelago. Without resolving the dispute, a peace treaty between the two countries (still lacking since the end of World War II) is unlikely.

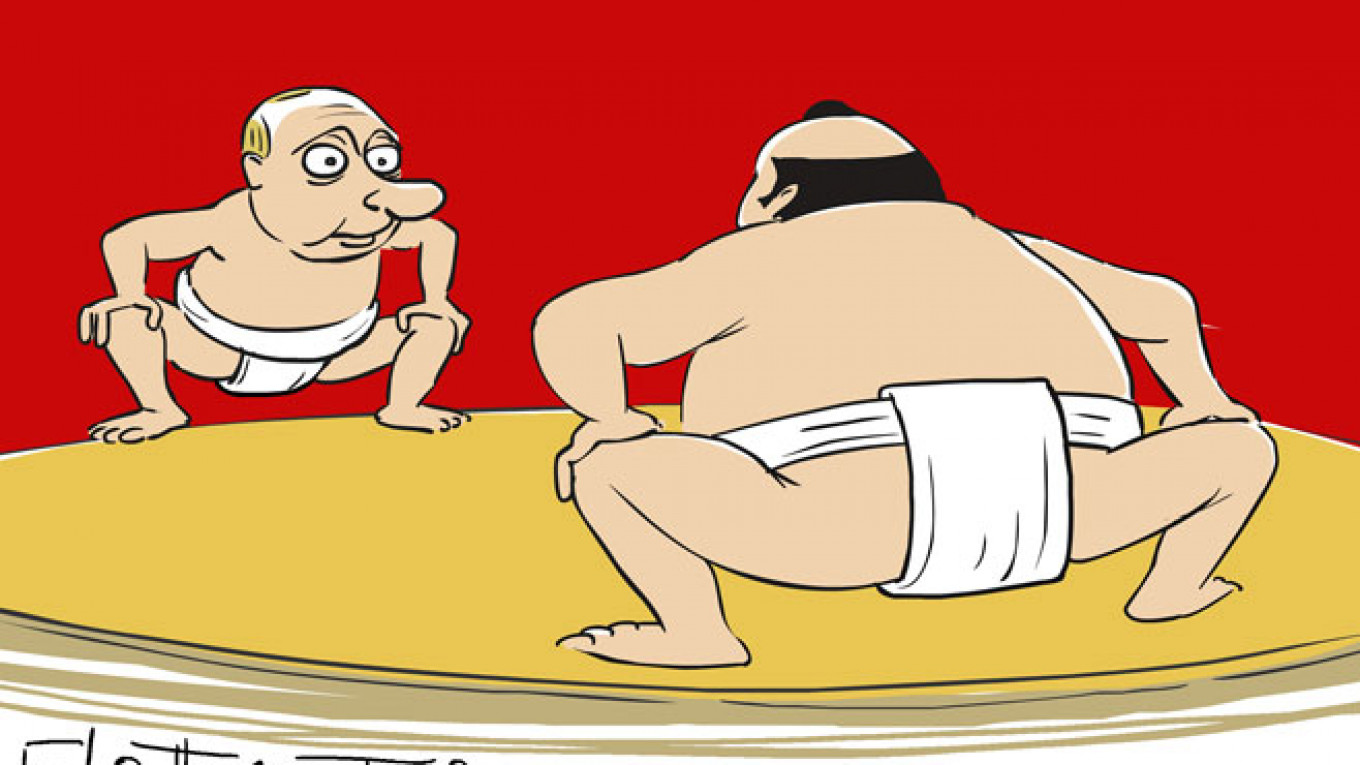

What the two sides now agree on is the increasingly urgent need to resolve their dispute, sign a peace treaty and finally start exploring the considerable complementarity of their economies. Since the return of Vladimir Putin, who is viewed in Japan as a more promising interlocutor than Dmitry Medvedev (who has twice visited the contentious islands), Japan has worked adroitly to cultivate trust with the Kremlin.

The frequency and level of their engagement has been unprecedented, and was increasingly seen in both countries as the best chance in a generation for a peace treaty.

The burgeoning rapprochement was driven underground last year by the conflict in Ukraine. There is only so much room for Tokyo's response to diverge from Washington's before the Beltway loses patience and questions Japan's "reliability.'' And yes, Japan went along with the rest of the G7 in passing sanctions, though it has been considerably more restrained toward Russia than some of its colleagues in that group.

But give the two countries credit for keeping the momentum in their relations alive in the face of powerful countervailing winds. The two leaders have continued to find ways to meet on the sidelines of multilateral conferences and reassure one another that they can keep the momentum going until U.S.-Russia tensions in Europe subside.

But with the new emphasis on BMD in the U.S.-Japan alliance, waiting out the geopolitical storm might just get a little harder.

Revisions to Russia's official military doctrine were made last December by presidential decree that point specifically to growing fears of BMD architecture on the country's periphery.

Article 12 of the doctrine now reads like a starter kit for any neighbor looking to antagonize Russia: Step 1, exert pressure on Russia by forming a military alliance with one of its neighbors, Step 2, deploy BMD hardware, Step 3, make claims to territory under Russian control. Japan, however unwittingly, now meets all of these conditions.

The card Russia now holds is that enhanced U.S.-Japan cooperation on BMD "changes the strategic equation," so how can Russia continue to see the U.S-Japan alliance as a source of stability if it threatens the country's strategic deterrent?

This would not be the first time that a U.S. policy sideswiped a Russia-Japan peace treaty, but since the end of the Cold War, the United States has actually been rather adamant that Japan patch things up with Russia.

Russia is not seen as a threat to Japan, or the U.S.-Japan alliance, and the guidelines actually leave the possibility open for cooperation with third countries in areas such as maritime security and disaster relief — areas where Russian partnership could be particularly effective.

Everything now hinges on how Russia responds to the new guidelines. If U.S.-Japan BMD cooperation is seen as a threat, Japanese Prime Minister Shinzo Abe's Russia reset is dashed, as is the hard-earned trust between the two leaders and any chance for a peace treaty in the near future.

If Russia chooses to close ranks with China on the BMD "threat," Russia-Japan relations go to the very back of the freezer. Japan can't be encouraged by Russia's decision to participate in "Victory Over Japan Day" ceremonies in Beijing this September, and will no doubt be paying close attention to discussions between Russia and China at the Shanghai Cooperation Organization summit in Ufa this July.

Let us hope that the BMD issue does not do to Russia and Japan what it did to U.S.-Russia relations in 2009. That would be like a bad sequel, with essentially the same plot, but in an exotic foreign locale. Let us hope that Abe and Putin hold on tight to their goal of a peace treaty, and can somehow manage to prevent a whole new dispute from arising between them in the meantime.

Devon Tucker is an international master's candidate at University College London and the Higher School of Economics, Moscow, where he researches relations between Russia, Japan and the U.S.

A Message from The Moscow Times:

Dear readers,

We are facing unprecedented challenges. Russia's Prosecutor General's Office has designated The Moscow Times as an "undesirable" organization, criminalizing our work and putting our staff at risk of prosecution. This follows our earlier unjust labeling as a "foreign agent."

These actions are direct attempts to silence independent journalism in Russia. The authorities claim our work "discredits the decisions of the Russian leadership." We see things differently: we strive to provide accurate, unbiased reporting on Russia.

We, the journalists of The Moscow Times, refuse to be silenced. But to continue our work, we need your help.

Your support, no matter how small, makes a world of difference. If you can, please support us monthly starting from just $2. It's quick to set up, and every contribution makes a significant impact.

By supporting The Moscow Times, you're defending open, independent journalism in the face of repression. Thank you for standing with us.

Remind me later.