When pragmatic negotiators in Minsk left two days free before the start of the cease-fire in Ukraine, both sides exploited that opportunity to continue the fighting. Pro-Russian separatists launched an all-out attack on Debaltseve in an attempt to force the Ukrainian army troops encircled there to lay down their arms.

And as if in retaliation, the Ukrainian army continued shelling residential areas of Donetsk and Luhansk. Most observers predict that the relative calm that dawned on Sunday will not mark the start of a wider peace. Nor will it become something akin to the Dayton Accords that ended the Bosnian War and the breakup of Yugoslavia. How might the situation develop now?

The new Minsk agreement includes too many "land mines" to hope for its ultimate success. Implementing the road map spelled out in Minsk will largely depend on timely action by the Ukrainian parliament, a body locked in tumultuous inter-factional rivalries that has already failed to uphold previous agreements.

Ukraine's entire ruling class must rally around Ukrainian President Petro Poroshenko in order to carry out the points he was compelled to agree to in Minsk. However, several prominent Ukrainian politicians disavowed the Minsk agreement almost the very next day.

Too many uncertainties are involved. For example, Kiev still refuses any direct contact with representatives of the self-proclaimed Luhansk and Donetsk People's Republics, referring to them as "terrorists."

However, the success of any elections held in these special regions, constitutional reform, the restoration of social services in the Donbass and related questions depend on such contact. In addition, the Minsk agreement stipulates that Kiev must first meet a number of conditions before it can get back control of about 400 kilometers of the Ukrainian-Russian border — an area that Kiev politicians call the "window of war" — by the end of 2015.

It is also a mistake to exaggerate the "obedience" of the separatists, all the more because Kiev shows no sign of ever granting them unconditional and complete amnesty. Many observers argue that when Igor Plotnitsky and Alexander Zakharchenko — leaders of the so-called Luhansk and Donetsk Republics, respectively — initially refused to sign the Minsk agreement, it was part of a charade that Putin had orchestrated to make it appear that he had forced them to the table.

That might be true, but in either case, those men lead upward of 25,000 to 30,000 separatists who have been to war, bled, lost comrades in battle and who are filled with hatred for the enemy. And now, just like that, they are supposed to "surrender" and retreat, to halt the offensive they began in January when they were just "five minutes away" from defeating approximately the same number of Ukrainian government soldiers near Debaltseve as they overwhelmed last summer near Ilovaisk.

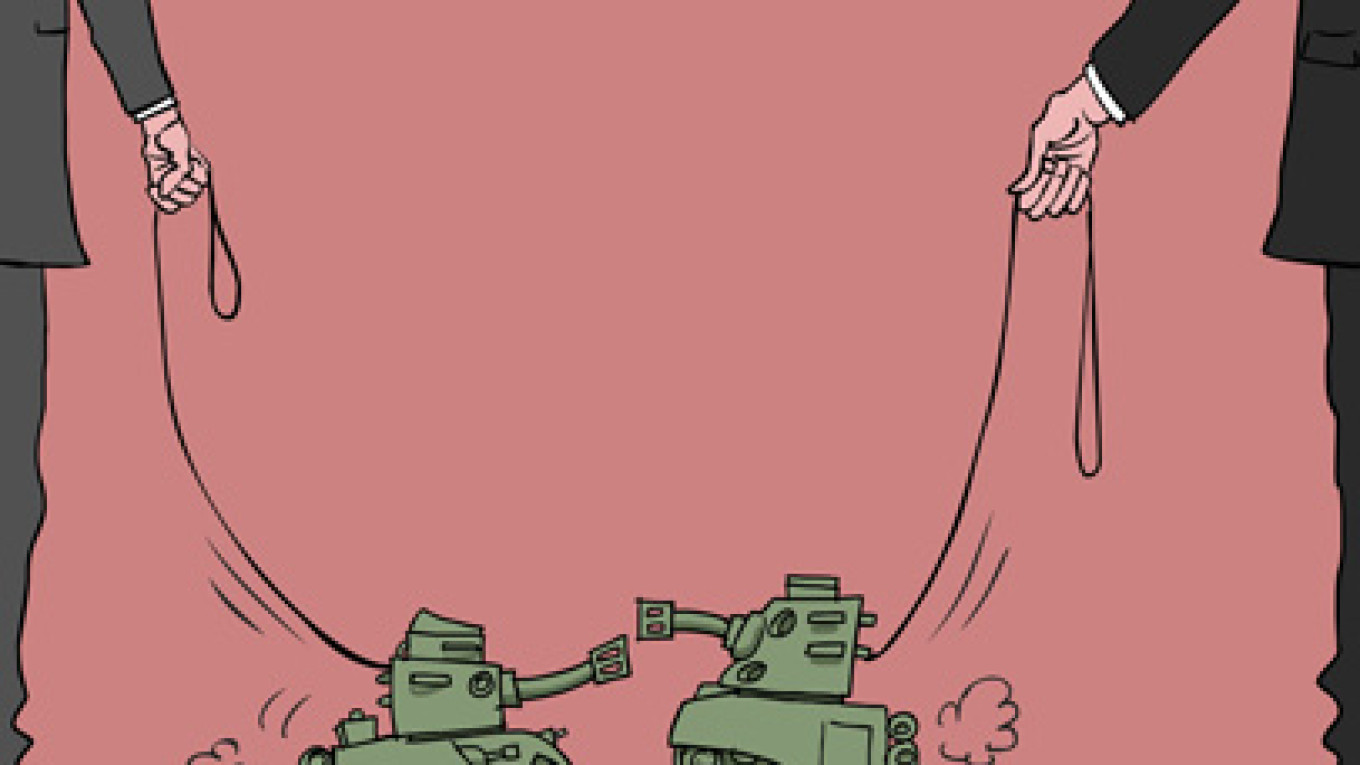

It might prove no easier to rein in those separatists than it is for Kiev to silence the ultra-nationalists who call for a continuation of the war.

Maintaining a cease-fire is always most difficult when the conflict involves not a confrontation between regular armies, but a battle between field commanders representing a variety of militias — including the numerous semi-guerrilla units fighting on the side of Kiev — in what would in this case be considered a civil war if not for the unofficial involvement of, at the very least, Russian military equipment and "advisers."

In any case, both sides can now observe at least a temporary truce. Given all the land mines in the Minsk agreement, it would be lucky if it lasted until summer. By that time the roads will dry out, the armies can replenish their ranks with reinforcements and resume their fighting.

In a worst-case scenario, the warring parties will break the cease-fire early on, once they begin withdrawing their heavy weapons. In the absence of a demarcation zone with peacekeepers, it is unlikely that anyone can ensure full compliance on this point, but the most important thing is that both sides stop shelling each other.

The main difference between the current Minsk agreement and the one reached in September is supposedly that now the two new powerful players, German Chancellor Angela Merkel and French President Francois Hollande, will put pressure on Kiev to comply with every single point.

That is partly true, but so is the fact that Europe is slowly but surely growing tired of Ukraine. Just how deep that frustration becomes will largely depend on how effectively Ukraine uses promised financial assistance to make reforms — $17 billion from the International Monetary Fund, European Union and other sources slated to arrive next month, and another $40 billion over the next four years.

So far, Kiev has done nothing to revive its comatose economy. And because that depends on concerted action by Ukraine's deeply divided ruling class, without a "third Maidan" to push them into action, that part of the equation looks just as doubtful as compliance with the Minsk agreement.

But there is another land mine that is potentially more powerful than all of the others combined — the fact that the United States was not directly involved in any way with the settlement negotiated in Minsk. And without Washington's active and effective participation, it is impossible to achieve anything like the Dayton Accords for Ukraine.

This is not only because Poroshenko keeps his eye on the United States in everything he does, or even because the IMF assistance cannot go through without official U.S. approval, but also because Washington continues to view Ukraine as a stage for countering Putin, whom it believes wants to change the global rules of the game and who has created a dangerous precedent as a sort of European Hugo Chavez and Ayatollah Khomeini combined.

Russian-U.S. relations have now sunk almost to the point that neither side even wants to shake hands with the other, or, more importantly, discuss anything of substance — including the political and military issues that were always on the table, even when economic cooperation was lacking.

Of course, as a cautious and somewhat indecisive leader, U.S. President Barack Obama will not go looking for trouble, but others in Washington are perfectly willing to step into the fray. For now, the United States is content to sit and wait and to give the initiative to the Europeans, who are unenthusiastic about the wisdom and viability of delivering Western weapons to Ukraine.

But the less the United States is constructively involved and committed to the process of reaching a settlement, the less likely it is that a lasting peace will emerge, that the points of the Minsk agreement will get implemented and that Kiev will fulfill its obligations.

Georgy Bovt is a political analyst.

A Message from The Moscow Times:

Dear readers,

We are facing unprecedented challenges. Russia's Prosecutor General's Office has designated The Moscow Times as an "undesirable" organization, criminalizing our work and putting our staff at risk of prosecution. This follows our earlier unjust labeling as a "foreign agent."

These actions are direct attempts to silence independent journalism in Russia. The authorities claim our work "discredits the decisions of the Russian leadership." We see things differently: we strive to provide accurate, unbiased reporting on Russia.

We, the journalists of The Moscow Times, refuse to be silenced. But to continue our work, we need your help.

Your support, no matter how small, makes a world of difference. If you can, please support us monthly starting from just $2. It's quick to set up, and every contribution makes a significant impact.

By supporting The Moscow Times, you're defending open, independent journalism in the face of repression. Thank you for standing with us.

Remind me later.