After Viktor Yanukovych was elected Ukraine’s president on Feb. 7, his slogan was “Stability and Reform.” In reality, he has delivered an impressive consolidation of power, while reforms are becoming less likely.

Impressively, Yanukovych formed a new government with hundreds of political appointees on March 11, two weeks after his inauguration. The presidential administration, parliament and government are all controlled by him. Political gridlock has been replaced with steamrolling. His new government looks like his government of 2002 to 2004, delegating power to big businessmen from eastern Ukraine who pursue their own agendas.

The newly elected president quickly visited Brussels, Moscow and Washington. His first big task was to reduce the price of gas from Russia by 30 percent, and he succeeded at receiving economic benefits (cheaper gas) for non-economic benefits (a longer lease on the Sevastopol naval base) on April 21.

His second task was to adopt a realistic budget for 2010, which was quickly done on April 27. Officially, the budget deficit is 5.3 percent of GDP.

A third task is to present a reform program for his five years in power, which is supposed to be unveiled Wednesday. A few reforms are under way, particularly a big deregulation law of the kind Russia adopted in 2002, a new law on the national bank and a law on state procurement.

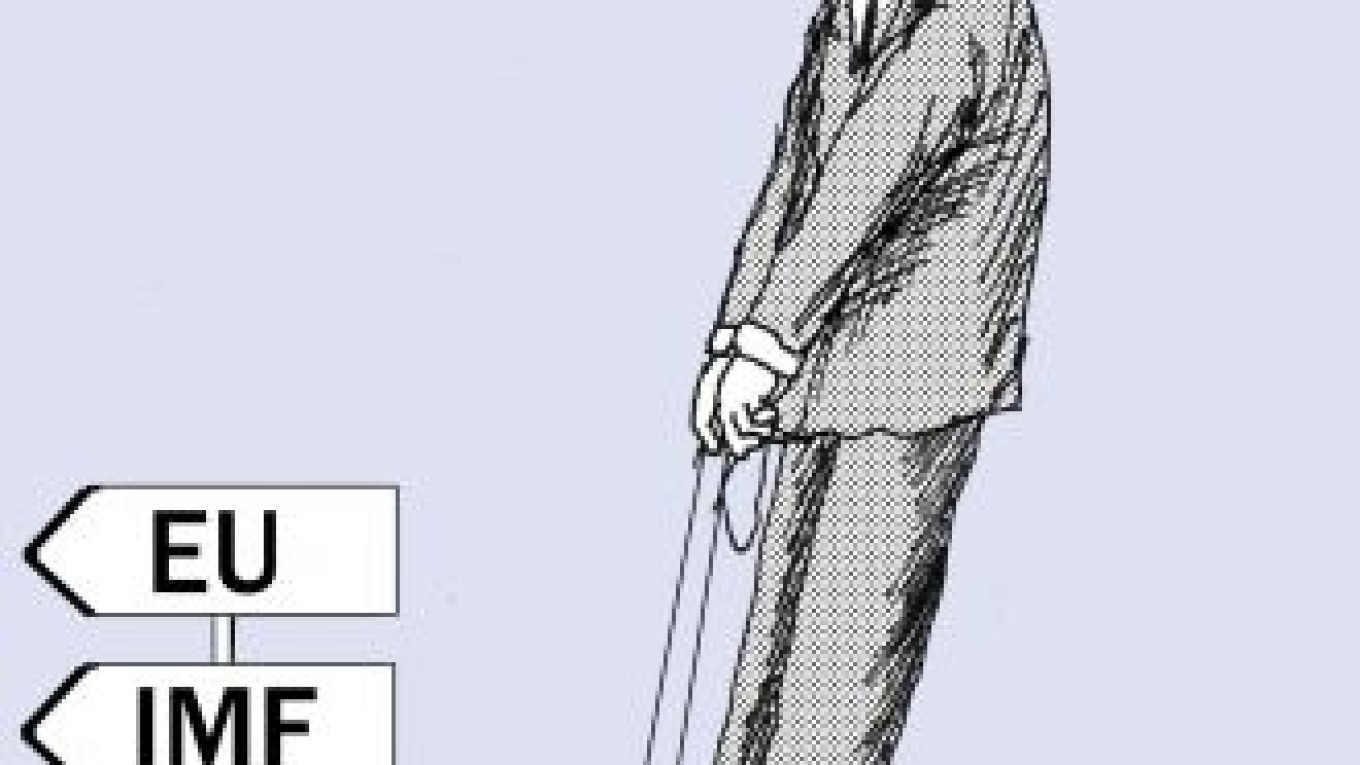

But the reforms appear fewer, less essential and slower in their coming than anticipated. Ukraine is pursuing no serious negotiations with the International Monetary Fund or the European Union. Without their engagement, reform will be that much more difficult. This is the time for Yanukovych to act and engage with them.

The new government seems to relax in hubris, feeling that things have gone too well. Recently, Prime Minister Mykola Azarov declared that GDP had grown by 8 percent in April in annualized terms, and industrial production no less than 17.4 percent. Economic recovery is easy because GDP plummeted by 15.1 percent last year and the previous government resolved the crisis with devaluation, budget cuts and IMF financing. Ukraine’s economy returned to growth late last year.

But Ukraine’s recovery remains precarious. After soaring by 75 percent this year, the Ukrainian stock market erased the whole increase as market hopes for fast recovery were replaced by fears of no more IMF cooperation. Ukrainian bank lending remains frozen with 30 percent to 35 percent of all loans nonperforming. The new government needs to pursue energetic market reform to secure economic revival and development.

Ukraine’s government has talked about a new three-year agreement with the IMF with financing of $19 billion, but no negotiations are taking place, only consultations. Since Ukraine no longer faces financial emergency, the IMF is tightening its conditions. It will only assist Ukraine with loans if Ukraine undertakes serious reform in four areas: exchange rate policy, the central bank, the budget and energy reform.

At present, the IMF is only satisfied with Ukraine’s exchange rate regime because the rate is unified, market-adjusted and floating. Inflation has fallen from 31 percent in May 2008 to 9.7 percent in April, and it should drop further.

The government has busted its own budget by raising social expenditures retroactively from January through the adoption of its social standards law, which the previous government opposed. It alone added 2.5 percent of GDP to public expenditures, while the whole world is slashing them. Nor is the government prepared to trim the astronomical pension expenditures. The IMF wants the government to cut the budget deficit by about 3 percent of GDP, which the government is not doing. Ukraine lacks the financing to cover this deficit.

The key IMF and EU demand has been energy reform to abolish price wedges, render the energy sector transparent and improve governance. The IMF and EU want Ukraine to separate the gas transit system from Naftogaz, to raise some artificially low gas prices and to adopt a law on the gas market. The gas sector remains the key source of rent seeking. But after having cut the price of Russian gas, the new government has apparently decided to do nothing more. A new law on Ukraine’s central bank is under way, but the question is if it will make the bank independent and transparent, putting an end to the practice of big businessmen sitting on its board and facilitating the refinancing for their own enterprises.

Today, Ukraine does not really need IMF financing. Its reserves are plentiful at $26.4 billion, almost a quarter of GDP, and current accounts are balanced. But foreign businessmen are not keen about investing in Ukraine if they see that the government is so reluctant to reform and make the economy more transparent that it opposes an IMF agreement. The banking system may face another run, if people are convinced that the central bank only serves the interest of a few big businessmen. The IMF has no need to finance Ukraine, while it is ready to support credible reforms. Without IMF approval, the World Bank can do little in Ukraine.

Ukraine’s relations with the EU appear considerably worse. In Brussels, the accusation runs that the Ukrainian government wants EU a la carte, which arouses great affront. The EU-Ukraine agreement of March 23, 2009, on the renovation of the gas transit system appears dead. Ukraine should be negotiating a European association agreement intensively now, but the Europeans feel increasingly alienated because they do not see serious intent on decent reforms while they are concerned about repeated claims about human rights violations.

These are still the early days, but the new Ukrainian government had better realize that it needs close cooperation with both the IMF and EU to steer the country out of its severe economic impasse. It needs to do so now as the reform program is being unveiled.

Anders Åslund, a senior fellow at the Peterson Institute for International Economics, is the author of “How Ukraine Became a Market Economy and Democracy.”

A Message from The Moscow Times:

Dear readers,

We are facing unprecedented challenges. Russia's Prosecutor General's Office has designated The Moscow Times as an "undesirable" organization, criminalizing our work and putting our staff at risk of prosecution. This follows our earlier unjust labeling as a "foreign agent."

These actions are direct attempts to silence independent journalism in Russia. The authorities claim our work "discredits the decisions of the Russian leadership." We see things differently: we strive to provide accurate, unbiased reporting on Russia.

We, the journalists of The Moscow Times, refuse to be silenced. But to continue our work, we need your help.

Your support, no matter how small, makes a world of difference. If you can, please support us monthly starting from just $2. It's quick to set up, and every contribution makes a significant impact.

By supporting The Moscow Times, you're defending open, independent journalism in the face of repression. Thank you for standing with us.

Remind me later.