"I really expected to stay only a year when I went to Russia, but I needed more time to master what I was learning, and one year led to the next," Flory said by telephone from her home in Paris. The opportunity to study at the conservatory arose after she became a prize winner at the 1970 Jacques Thibaut Competition. "Kogan was on the jury and suggested I study with him in Moscow. There was an exchange program, and I was able to obtain a bursary from the Russian government."

For those who regard music education in Russia as more regimented and authoritarian than in the West, Flory's experience provides ample confirmation. Because Kogan was away on tour for much of the time, Flory worked extensively with his assistant, Valadar Bronin. For the first 15 days, they worked on nothing but the G major scale. "Finally I had my first lesson with Kogan, and he asked what I would play. 'A scale,' I replied. 'What scale?' 'Any scale you want,' I said, noticing that Bronin's eyes practically popped out of his head because I didn't say the G major scale. Kogan asked for C minor, and his comment was, "Not bad for improvising."

Any sort of compliment from Kogan was a victory for Flory, who looked up to him as a violinist-god. "There was nobody whose playing I loved more -- at every concert I was very moved," she said.

But Kogan's unbending Soviet methods did not mesh with Flory's more Western approach. "He really wasn't a good teacher, at least for me. He would never pick up his violin and illustrate a point. And only when a piece was technically perfect did he allow you to consider its musical qualities. I was used to more freedom. Psychologically, his approach wasn't right for me."

One experience indicative of Kogan's taskmaster approach came when she was preparinga piece for the Tchaikovsky Competition. At a lesson one evening, he told Flory to return the next morning and play it perfectly. "'But it's already 10:00,' I said. He told me to go home and practice for four hours, then to go to bed at two and sleep till 6:00, then practice four hours more." She went back to the dormitory, and a friend who noticed that she was crying decided to give a party in his room. "We were drinking and played a game where two people stand back-to-back and try to lift the other one up. I ended up falling and breaking my shoulder. So I didn't play the concerto for Kogan, and I couldn't play in the competition, either."

Unlike other conservatory students, Flory's studies consisted of solely of her violin lessons and the Russian language. "Other students took courses in theory, music history and -- very important -- history of the Communist Party. But I didn't even play in an orchestra or chamber groups," she said.

Flory recalls only three other students from the West studying at the conservatory while she was there. "I lived in the dormitory on Malaya Gruzinskaya and had a different roommate each year, probably because the authorities didn't want anyone to get too friendly with me," she recalled. "I assumed that my roommates made reports to the KGB, but I don't think the room was bugged. At first I was very open in what I said, but I soon realized that I couldn't always speak the truth. For instance, one student told me America's claim that a man walked on the moon was total nonsense. How can you respond?"

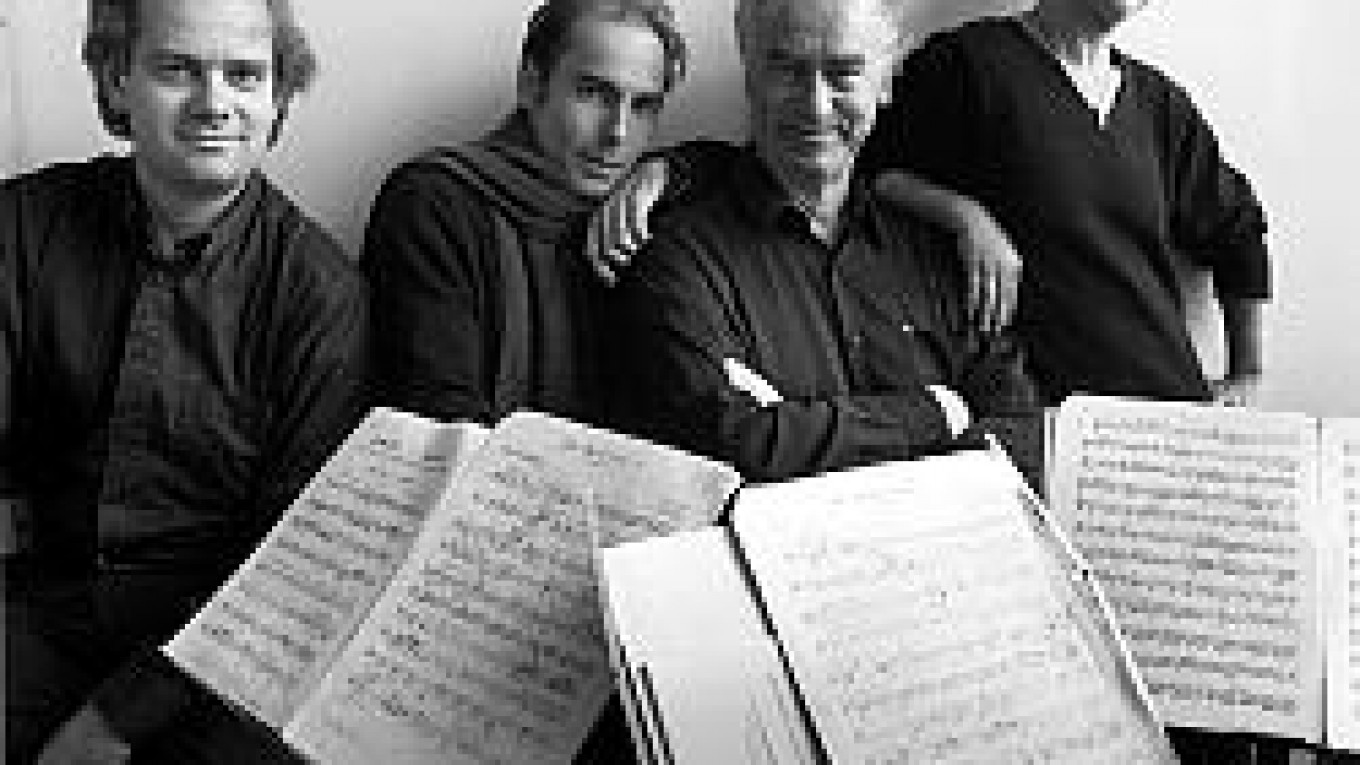

Despite the drawbacks of her Moscow studies, Flory credits them with making her listen to her playing more acutely "because [Kogan and Bronin] were so critical of every detail. And sometimes people say I have a Russian technique." Subsequently, she continued her studies in London with Yfrah Neaman and came to the attention of Yehudi Menuhin. When Flory returned to France in 1982, the violinist Nicolas Risler became a frequent chamber music collaborator and eventually her partner. In 1989 the two formed the Arpeggione Quartet, which became a laureate of the Evian International Quartet Competition that same year. Among the quartet's many subsequent distinctions, Menuhin chose it to celebrate his 80th birthday in 1996 at the Palais de l'?“lys??e in Paris. Flory and Risler have been constants in the quartet; more recent members are Rapha--l Chr??tien, the cellist since 2001, and Patrick Dussard, who joined as violist last year. Coincidentally, Dussard also spent some months studying in Russia.

Likewise, the world premiere to be offered by the Arpeggione -- the String Quartet No. 3 by Anthony Girard -- also has a Russian connection. Girard, 45, counts his studies with Valery Arzumanov, a Russian composer now living in Paris, as crucial to his artistic development, and has written a monograph about him. Works by Girard, which number nearly a hundred, have previously been heard in Moscow as well as in Voronezh, Sochi and Samara. Apropos of his new quartet, Girard has said that "in a genre reputed to be austere ... I have wanted to introduce here and there some humor ... a certain smile mixed with tenderness."

Another novelty will be a quartet by the late 18th-century composer Hyacinthe Jadin. According to Flory, the piece has a first movement reminiscent of Franz Joseph Haydn, a minuet with an unusual unison texture and a polonaise finale. Maurice Ravel's early Quartet in F closes the program.

A Message from The Moscow Times:

Dear readers,

We are facing unprecedented challenges. Russia's Prosecutor General's Office has designated The Moscow Times as an "undesirable" organization, criminalizing our work and putting our staff at risk of prosecution. This follows our earlier unjust labeling as a "foreign agent."

These actions are direct attempts to silence independent journalism in Russia. The authorities claim our work "discredits the decisions of the Russian leadership." We see things differently: we strive to provide accurate, unbiased reporting on Russia.

We, the journalists of The Moscow Times, refuse to be silenced. But to continue our work, we need your help.

Your support, no matter how small, makes a world of difference. If you can, please support us monthly starting from just $2. It's quick to set up, and every contribution makes a significant impact.

By supporting The Moscow Times, you're defending open, independent journalism in the face of repression. Thank you for standing with us.

Remind me later.