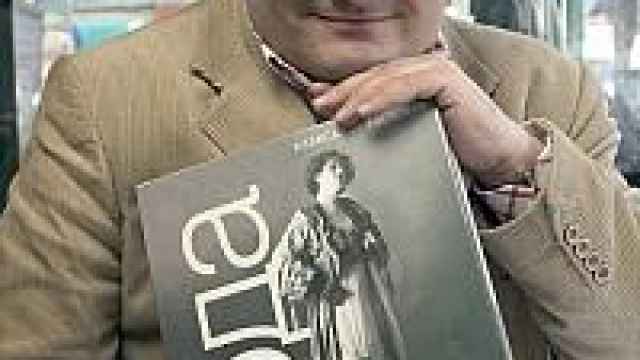

Variously a theater costume designer, interior designer, writer, teacher and collector, Vassiliev recently raided his trove of 20,000 photographs of Russian couture for an illustrated book, "Russian Fashion: 150 Years in Photographs," which will come out later this month from Slovo publishers.

Beginning with the earliest black-and-white photographs of the 1850s and stretching to the end of the Yeltsin era, the book is the most comprehensive record of Russian fashion ever written, Vassiliev says. But the 45-year-old author anticipates that the section devoted to the Soviet period -- a time that may inspire memories of Nikita Khrushchev's ill-fitting suits and kerchiefed cow girls -- will be most interesting for Russian readers.

"Of course, Russia during the Cold War, and its fashion, is known in the West only through James Bond movies," Vassiliev generalized. While in "From Russia With Love" former beauty queen Daniella Bianchi spends a good deal of time draped in a sheet, the reality was a little less sexy.

Bans on low necklines, bare legs, jeans, platform shoes and hippie gear were part of an ongoing struggle against Western decadence, the author said, leafing through the book.

Even trousers were long confined to sport. Yet "a hint of glamour" was permissible, and the book shows pictures of 1960s-era starlets such as Svetlana Svetlichnaya with high hairdos and dangling earrings. In 1965 the first bikinis appeared -- nine years after their invention in France -- followed by the miniskirt in 1969.

Some particularly Russian fashion trends remained constant, though. "Fur hats, high boots [and] folk embroideries," Vassiliev listed, calling these wardrobe perennials "a mixture of allure, lavishness and folklore."

While Soviet fashion could be drab, it was never entirely cut off from the outside world, and retained some "razzmatazz," the author said in his colorful English. Entry routes for Western fashion were Poland, Finland -- whose tourists began cruising to Leningrad earlier than other visitors -- and the Baltic states, which had a highly developed fashion industry before the war and subsequent Soviet occupation.

But fashion modeling did not attain the cachet it has in the West until the 1990s, Vassiliev said. Houses of Patterns, the central organizations that designed clothes for the masses, employed XXL models. And the retirement age for models was 78.

Alexandre Vassiliev / For MT Vassiliev finds himself combing markets for the antique photos, since few survived the 20th century. | |

As a Moscow teenager in the 1970s, Vassiliev wore his hair "in The Beatles' style" and posed for a photograph in a T-shirt with a print of suspenders clutched by two hands, which, he believes, came from London. In the picture, Vassiliev is holding a guitar. "It was fashionable just to carry a guitar. I couldn't play it," he recalled with a laugh.

Unsurprisingly, the young Muscovite, who had already begun collecting clothes and costume photographs from trashcans and the city's three antique stores, was desperate to go to the West. He found a way at the age of 23 by marrying a Frenchwoman. "It was a marriage of arrangement," he commented. "But it was consummated."

Thanks to support from his own family in Moscow and its emigre wing in France, Vassiliev quickly found his feet in Paris. He began designing for theater, opera and ballet productions, and furnished an apartment with Russian antiques. Amassing a collection of thousands of items of Russian clothing, Vassiliev taught fashion history and stage design at art schools across Europe.

A 1987 shot shows the young Parisian wearing a jacket decorated with words in Cyrillic script from Jean Paul Gaultier's Russian-inspired collection. "It was very fashionable in the 1980s," he said.

Now, though, Vassiliev spends most of his time in Moscow, where he heads an interior design company that specializes in antique decor. "I have nouveaux riches Russian clients who are in search of history," he said. In his spare time, he teaches a course in management and the theory of fashion at Moscow State University.

Sitting on a sofa in the cafe last Friday, the author turned a sharp tongue on a hapless waitress with well-lacquered hair who told him that it cost more to sit in the comfortable seats. "No problem at all. You also need money to buy hair spray. I understand you," he said.

While Vassiliev hopes this book will be a success, he is already planning his next project -- a catalogue of his dress collection, which includes gowns donated by ballerina Maya Plisetskaya, French actress Leslie Caron, and "Cold War-era Russian movie stars." Ultimately, he hopes to house the collection of around 15,000 items dating back to the 18th century in a purpose-built museum.

Vladimir Filonov / MT Vassiliev drew from family archives for the 2,000 photographs in his new book. | |

Not that it's easy to find pictures of elaborately dressed people in pre-Revolutionary Russia, Vassiliev said, since those well-off Russians who failed to take their family albums into emigration often died in the gulag. "The ones that are available are mainly from very modest origins, and who wants photos of modest origins? They are not spectacular enough."

While the book, which is priced at around $100, is bound to attract collectors with deep pockets, Vassiliev is keen for the field to widen. "When collectors are paying a good price for them [photographs], it means that they [dealers] aren't throwing them away."

The book deliberately ignores the Putin era. "I do not have enough historical recul -- perspective -- to analyze," Vassiliev said, lapsing into French. "I think future historians will do it probably better."

Still, the fashion historian has plenty of opinions on style today. Describing 1990s-era fashion as "twinkly" and "a Russian salad," he commented that there has since been "a certain turn toward elegance." French influences have taken the place of Orientalism, he believes, and designers have learned from their well-traveled customers.

While veteran designers such as Slava Zaitsev and Valentin Yudashkin "marked their era in the past," Vassiliev sees today's frontrunners as young designers Igor Chepurin, whose clothes, he said, are "feminine, elegant, westernized," and Tatyana Parfyonova, who creates "arty, sporty pret-a-porter."

Nevertheless, in show business vulgarity reigns, Vassiliev said, hard put to name a well-dressed celebrity until he finally settled on actress and director Renata Litvinova. The diamonds that New Russians buy for their wives and mistresses are this big, he exclaimed, putting his hand around a tea-glass. "A real Mardi Gras."

"Those who are possessors of wealth love to show off," he commented. "They love to be very much a fashion victim."

"Russian Fashion: 150 Years in Photographs" (Russkaya Moda. 150 Let v Fotografiyakh) will be published by Slovo on Sep. 25.

A Message from The Moscow Times:

Dear readers,

We are facing unprecedented challenges. Russia's Prosecutor General's Office has designated The Moscow Times as an "undesirable" organization, criminalizing our work and putting our staff at risk of prosecution. This follows our earlier unjust labeling as a "foreign agent."

These actions are direct attempts to silence independent journalism in Russia. The authorities claim our work "discredits the decisions of the Russian leadership." We see things differently: we strive to provide accurate, unbiased reporting on Russia.

We, the journalists of The Moscow Times, refuse to be silenced. But to continue our work, we need your help.

Your support, no matter how small, makes a world of difference. If you can, please support us monthly starting from just $2. It's quick to set up, and every contribution makes a significant impact.

By supporting The Moscow Times, you're defending open, independent journalism in the face of repression. Thank you for standing with us.

Remind me later.